Mexico and the World

Vol. 11, No 1 (Summer 2006)

http://profmex.org/mexicoandtheworld/volume11/1winter06/chapter8.html

CHAPTER EIGHT

Global and Local Industrial Development in Tijuana

ORIGINS AND TENDENCIES

Emilio Hernández, Alejandro Mungaray and

Juan M. Ocegueda-Hernández

FOUNDED IN 1889, Tijuana is a young city with socioeconomic processes that may be explained in great part by its proximity to San Diego. The origin of Tijuana's spatial structure-which revolves around services (tourism and commerce)-explains why practically all the main roads converge on the traditional central zone. Industries have, however, slowly established themselves in Tijuana, significantly modifying the functional urban structure (Alegría 1995)· Therefore, in spite of the fact that since the 1970s and during the 1980s the Programs of Industrial Parks and Cities (Garza 1989; Mungaray and Alvarez 1987) have given Tijuana more resources for an orderly industrial growth, the form taken by that growth has delayed every possibility of urban planning (Mungaray 1997).

Tijuana's incorporation of the urban nodes of global production has produced a divided city. The first area, on the west side, is a concentration of the traditional services sector which characterized its urban origins. The second area, the eastern part of the city reflects the growing presence of the maquiladora industry, which is spreading because this type of company is oriented toward foreign markets. The urban expansion to the east is characterized by a pronounced sociospatial segregation between the maquiladora industry and the labor force, which is associated with this economic activity primarily because of the workers' low levels of education and skills. The situation is worrisome because Tijuana's municipal services are more abundant and continue to expand in the traditional zone to the west, but the urban demographic and industrial growth is taking place mainly on the east side of the city where land reserves are located.

The Global and the Local

During the 1990s, the analysis of the transformation of cities was approached mainly as part of the economic globalization processes. In the tradition of California's regional development, globalization is defined as an interconnected network of urban nodes (cities), beginning with their production flows (Scott et a1. 1999:7-10). Some productive processes that relocated could gain locational advantages-and related cost reductions (Scott 2000; Sassen-Koob 1991) because of communication and transportation developments (Castells and Borja 1997) which allow for the intensification of financial flows and technological knowledge.

The global city offers a conceptual and analytical framework for approaching Tijuana's urban processes, if we understand global city to be the spatial organization of a new international division of labor, with both San Diego and Tijuana playing specialized roles (Friedman 1986:69; Baum 1999). Like a network of urban nodes with different levels and functions, this global city spreads over a wide transborder region. It functions as the central nervous system of a new regional economy where companies and cities must interact constantly and flexibly, adapting themselves to each other in this urban network. The relationship must be characterized by dialog that will determine the destiny of both cities and their citizenry (Castells 1997:23).

One form of transborder division of labor lets the companies and citizens take advantage of the services and advantages the San Diego area derives from the concentration of research and development tasks. Although highly qualified productive activities are being developed in Tijuana, low-skilled productive activities still predominate.

A concentration of manufacturing jobs in one sector of the global city temporarily throws the labor market out of balance, since in the other sector industrial restructuring and the growing demand for highly qualified workers raise the levels of education demanded. A large segment of the urban population is thereby excluded, a segment whose access to the urban labor market has been differentiated.

Globalization and Transborder Processes in Tijuana

Local communities belonging to this global city face challenges related to the city's nature as an urban society and its ability to implement active territorial and civic policies (Granger and Blomquist 1999).The approach of the global city allows for the consideration of the sociospatial impact in places where global productive activities take place. A good example is the experience of Tijuana because its adjacency to the Mexico-U.S. border (Figure 8.1) has made it a major receiving zone of international companies dislocated from their original sites, which are producers of jobs for non-skilled workers.

From a local perspective, it is clear that Tijuana is an important site in the network of nodes that include California and East Asian countries (Won and Kenney 1997), since it supplies an urban infrastructure sufficient for sheltering decentralized productive processes that demand a low-skilled labor force, required by their global production flows. Consequently, interactions in the transborder urban space, particularly in Tijuana, reflect the transformation of the international economic processes. However, they also contribute to Tijuana's rapid urban, economic, and social transformation.

The evolution of Tijuana's economy presents a scenario where the encounter of the global and the local takes on a special meaning. The commercial and services sectors originating in the flows of transborder tourism persists in the east of the city. The character of the transborder consumer, resident on both sides of the San Diego-Tijuana border, remains unchanged. For example, some 40,000 persons residing in Tijuana work in the U.S. and an estimated 10,000 San Diego residents work in Tijuana. Of the 1.4 million people who crossed the border in one direction or the other in 1998 (Tijuana City Council 2000), 74 percent of those who went to Tijuana from San Diego did so for recreational purposes. Of the 1.6 million who crossed from Tijuana to San Diego, 86 percent did so to shop (San Diego Association of Governments 1998). In addition, it has been estimated that Tijuana residents spend $2.8 billion a year in San Diego (Tijuana City Council 2000).

What is new is the maquiladora industry's push toward the east and southeast, as it moves workers who are part of global production processes into the local labor market. The inclusion of the workers in the maquiladoras, however, shows selectivism. Companies offer both high-level executive positions and jobs for unskilled labor. The former, of which there are few, belong to technicians with higher education degrees; the latter are taken by those with little schooling. In cities of developed countries, employees not working in global production processes receive relatively low wages; in Tijuana, employees working in global production processes receive wages as low as those who work in traditional companies and processes.

The majority of maquiladora impresarios live in San Diego, not Tijuana. Because of the very character of global production, they can manage various production sites from San Diego, elsewhere in the United Sates, or from an Asian country. In contrast, employees who live in Tijuana and work in California, or vice versa, can be characterized as transborder because their activity may or may not be linked to global processes. In the first case, they would be global transborder workers; in the second, simply transborder workers.

Population Aspects

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the urban expansion of Tijuana has been associated with great flows of migratory groups. Because the city is a convergence point for those coming from different areas of Mexico's interior, it has a markedly heterogeneous culture. The periods from 1921 to 1930 and from 1940to 1950 are significant for their growth rates. During the first, which was related to the Great Depression, large numbers of Mexican workers in the U.S. were sent back to Mexico. A considerable percentage of these settled in Tijuana. The second period, which coincided with U.S. entry into World War II, saw the establishment of the Bracero Program, in which Mexicans were hired as agricultural laborers in the U.S. When this program ended in 1964 and a national policy of integrating the border territory with the country as a whole. Tijuana became the main recipient of those population groups who did not return to the Mexican interior.

Starting in the 1980s, there was a national transition toward policies of economic openness. The growing presence of companies connected with the world market during this period-because of the great migration of those attracted by the concentration of the export-oriented maquiladora companies and the job opportunities generated by them-once more accelerated the rates of population growth, which had slowed between 1970 and 1980.

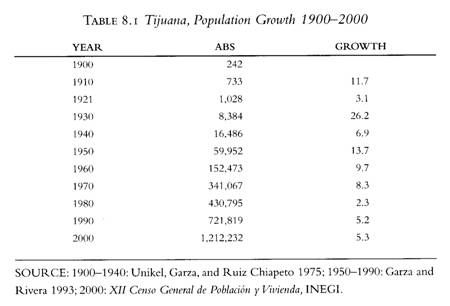

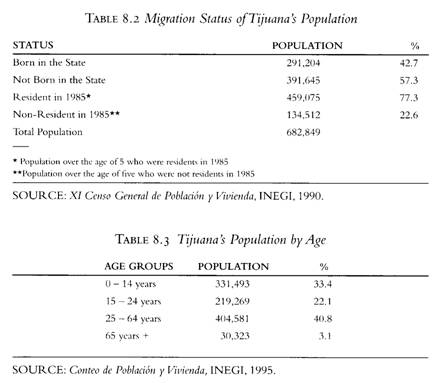

The composition of Tijuana's population shows a high percentage of nonnative people to the state, and recent trends show even higher proportions of migratory flows (Estrella 1998). This confirms one of the characteristics of the city, in which population growth is a constant that includes social processes such as employment, access to housing, social interaction among individuals, industrial localization, and transborder urban life (Table 8. I). In 1960, 65.4 percent of the population was not native to the state; 57.3 percent of Tijuana's population was not native to the state in 1990. Migration in the period from 1980 to 1990 indicates that the increase in population growth is largely explained by social growth, since nearly one-fourth of the population over the age of five did not reside in the state in 1985 (Table 8.2).

The concept of Tijuana as a city where migration flows has lost relevance when trying to explain population growth. Tijuana is itself a magnet for a population seeking to improve its living conditions, because of the ever-increasing possibility of employment produced by Mexican industrial policy in support the maquiladora industry, which is highly concentrated in Baja California.

This permanent migration explains why the city of Tijuana has a relatively young population, with 40.8 percent between 25 and 64 years of age, or of working age; 55.5 percent are from 0 to 24 years old; and 22.1 percent are between 15 and 24 years of age (Table 8.3). It is the municipality with the highest number of inhabitants in the state.

Economic Aspects

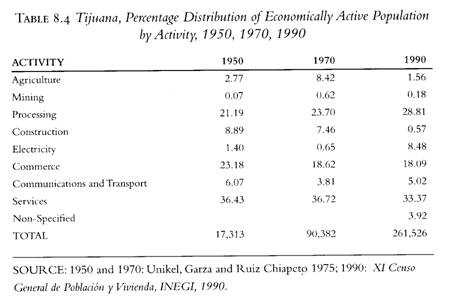

The economic growth of Tijuana in the early twentieth century was linked to the necessity of finding living spaces for the population residing in the San Diego area, just the other side of the border (Piñera and Ortiz 1985; Mungaray 1985). The evolution of its economic activity may be appreciated over time through the observation of the changes in the percentage distribution of the economically active population (EAP). Before 1970 it represented an open, interconnected economy, since 60 percent of the EAP worked in the commercial and services sector. The processing industry is that of arts and crafts linked with tourism and that of the production of food and beverages for the local market. The economic opening of Mexico began first in Baja California when a Free Zone was established there (Ramirez 1983).

From 1970 to 1990, there was, as a result, a remarkable decrease in commerce and services and an increase in the participation of the processing industry (Table 8.4).This change in employment was owing to the strengthening of the maquiladora industry, to an adjustment in commerce and services, and to a reduction in agricultural activities (Mungaray and Ocegueda-Hernandez 1995). The recent period may be considered as one where an interconnected sector, openly industrial, is strengthened and where economic activity is increasingly associated with the foreign market. The reduction of the agricultural work force may be explained not only by the economic change that favored urban activities, but also by the fact that a great proportion of transmigratory workers joined the services sector in San Diego. The census asks for a person's job description, not where they work.

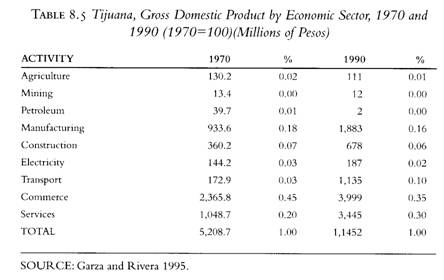

The participation of commerce in the gross domestic product indicates that the decline of commerce in favor of services is fundamentally the result of local industrial restructuring due to the unceasing growth of the maquiladoras (Table 8.5). This change in the participation of commerce and services may not be seen now as a characteristic of an openly interconnected economy but rather as derived from the necessities of the maquiladora industry's dynamic presence. The economic opening benefited foreign investment and Tijuana's location in the dynamic industrial area of Southern California in the 1980s and 1990S (Scott 1993, 1996) made it the main location for this type of industrial growth and transformed the local economy.

The predominance of the services sector (tourism and commerce), since the beginning of the twentieth century, oriented the spatial structure of Tijuana, causing that the development of the main roads had been toward its traditional central zone. When this spatial structure was overlaid with an industrial use, however, the urban functional structure was significantly altered. Thus, in the decade of the 1970s, and even more strongly in the 198os, the Program of Parks and Industrial Cities (Garza 1989) placed Tijuana in a new regional context: in 1975, there were 99 maquiladora plants employing 7,834 people; by July 2000, there were 794 plants with 193,118 workers.

The maquiladora industry has undergone constant relocation because the work force's access has proved permanently problematic. Toward the end of the 1970s, the maquiladoras relocated to the interior of low-income neighborhoods, where the work force resided, because the urban design and quality of the public infrastructure hampered the movement of workers from their place of residence to their work site. The opening of industrial parks allowed for the removal of those companies producing the most pollution in these areas, but the industrial parks were far from the central zone, which resulted in a combination of problems. The work force had difficulty getting to their jobs, and the companies struggled to get supplies and products through the international border crossing on time.

Employment and Unemployment

The EAP in Tijuana has grown over the last seven years, with men predominating in the gender category, and 20 to 44 year olds the predominating age group.

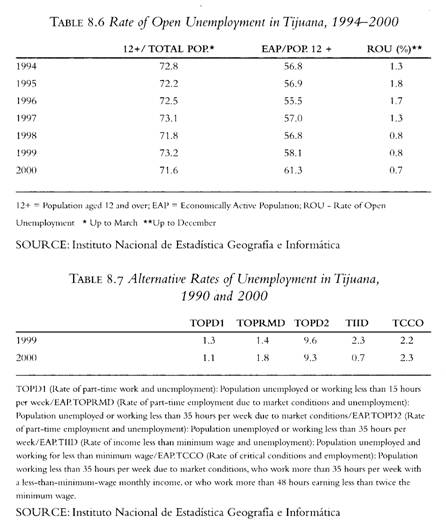

At the same time, the rate of open unemployment (ROU) is decreasing, down 50 percent from 1994 to 2000, when it reached a level of 0.7 percent. This information reflects an important expansion in employment associated with abundant investments within the maquiladora industry, which, at the state level and measured in millions of dollars, is six times greater than in 1993. Alternative indicators of open unemployment-magnitude of the underemployment (TOPD1 and TOPRMD) and of poorly paid jobs (TIlD and TCCO) as measures of unemployment-show no significant variation. Depending on the indicator by which it is measured, underemployment is 0.4 percent (TDA - TOPD1) or 1.1 percent (TDA - TOPRMD). The number of workers paid less than the minimum wage (TIlD - TDA, TCCO - TDA) varies between 1.5 percent and 1.6 percent of the total EAP. The TOPD2 rate, an indicator of unemployment and voluntary underemployment, is markedly high (Tables 8.6, 8.7).

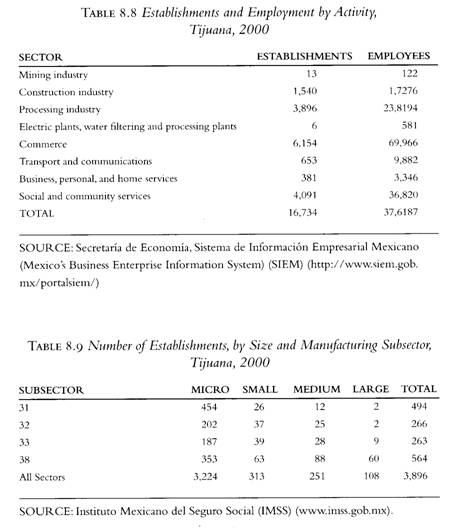

An analysis of the industrial sector and of the most important activities of the service sector shows a working population of 376, 187 distributed among 16,734 establishments. The processing industry and commerce are the most prominent, accounting for 63.3 percent and 18.6 percent of employment, and 23.3 percent and 36.8 percent of the establishments, respectively. In the processing industry, the maquiladoras contribute 77.6 percent of the jobs and 20 percent of the establishments. Social and community services, with 9.8 percent and 24.4 percent, and the construction industry, with 4.6 percent and 9.2 percent, also make an important contribution (Table 8.8).

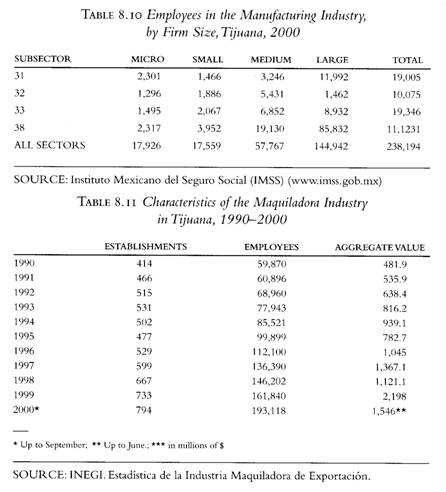

The structure of the manufacturing industry in Tijuana, composed mainly of micro businesses (82.8 percent of the total), does not differ significantly from that seen on a national level, since subsectors 31 and 38 are those that contain the largest group of companies of this type and of all other sizes. Sector 38, however, is the only one that shows a significant participation of large companies and the one that has the greatest number of medium-sized businesses. This information is associated with the concentration that the maquiladora industry presents in this type of activities. Despite their large number, small and micro businesses contribute only 7.5 percent of the manufacturing jobs. Considered together, their contribution rises to 14.9 percent, still much lower than the 60.0 percent the large companies generate. The maquiladora industry generates 77.6 percent, while 46.7 percent is generated by subsector 38, 8.1 percent by subsector 33, and 8 percent by subsector 31 (Tables 8.9, 8.10).

There are 15,867 establishments in the commercial sector, of which 15.3 percent are grocery stores; ro. 5 percent are misceláneas (small stores where different things, from stationery to groceries, are sold) and candy shops; 7 percent are clothing and shoe stores; and 6.4 percent are pharmacies, drugstores, and medical supply stores. There is also a strong informal sector, which is distributed over various areas of the city. 56.2 percent of these sites are found in the central zone, 13 percent in the La Presa area, II percent in Otay, 10.9 percent in La Mesa, and 8.9 percent in San Antonio de los Buenos.

In addition, a moving type of market occupies a total of 142 places per week, with the heaviest concentration in La Presa, which has 57. San Antonio de los Buenos has 32; La Mesa, 22; Mesa de Otay, 14; the Central Zone, II; and Playas de Tijuana, 6. The majority of the commercial activities of the city have to do with the sale of food and drinks; clothing; gasoline and propane gas; raw and auxiliary materials; transportation equipment; and vehicle repair parts and accessories.

Maquiladora Industry

The most important economic activity in Tijuana is the maquiladora industry, with a total of 184,756 employees in 779 establishments distributed over 52 industrial parks and centers. Notable among these are the New Tijuana Industrial City, with 130 plants generating 30,000 jobs; the Pacific Industrial Park, with 34 plants and 12,500 employees; and the Tijuana International Industrial Park, with 33 plants and 5600 employees. A large part of the city's maquiladora industry is dedicated to the production of television sets and electronic items. Of these, Samsung, Sony. Sanyo, and Panasonic are the most prominent. The extraordinary quantity of television sets produced in the city has earned it the name of "television capital of the world."

During the 1990S, the number of maquiladora establishments nearly doubled, the work force tripled, and the aggregate value in current dollars increased 4.6 times (Table 8.Il). This remarkable expansion of activities has spurred Tijuana's economic activity, although because of reduced productive links with local suppliers, the effect on the growth rate has been limited.

With respect to the economic and spatial factors, the impact of the global character on the urban configuration is evident by the high correlation between the location of the maquiladoras and the spaces occupied by the low-income, undereducated population occupied as laborers or factory workers in the secondary sector of the economy. The heaviest concentration of these is found toward the west and southwest side of the city, the area showing the most recent urban growth (Hernandez 2001).

A survey of the companies not located in industrial parks was taken by first scanning those districts which, according to the Tijuana Industrial Directory, contain manufacturing factories. A sample was then taken. Out of the 700 districts shown in the digitized list, only 310 have some type of industry. From these a sample of 491 companies distributed over 81 districts was taken.

The analysis of the distribution of the companies in the districts began with the construction of the concentration indices. A preliminary procedure was required, by which groups of companies located in the same general area were identified. This facilitated the analysis of the location of all the companies in the 81 districts, and grouping them according to eleven different types of industrial processes. The identification of groups of companies with a similar intra-urban location pattern was made by the method of principal components, allowing the expression of the intercorrelation of the location of the firms in a lower number of components or groups of firms. In this way one would be reducing the initial number of variables, eleven in this case, to a lower number of components or vectors which represent families of variables.

This study considers a matrix of 81 districts and II variables. The variables are: a) purified water-processing firms; b) arts-and-crafts firms; c) carpenter's shops; d) auto-body shops and upholsterer's workshops; e) assembly plants; f) blacksmith's shops; g) printing works; h) bakeries; i) restaurants; j) tailor's shops; and k) tortilla producers.

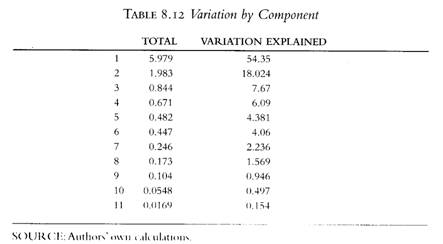

The method of principal components indicates that there are families of variables with a high correlation in two vectors, which have values of 5.979 and 1.983, respectively (Table 8.12). By dividing the value of the proper vector among the number of variables (II), one can show that the first vector represents 54.35 percent, and the second 18.02 percent of the total variation. The sum of the two vectors explains 72.38 percent of the total variation.

Generally the vectors with a value of less than I are eliminated from the analysis, since they have less weight than if they are considered as isolated variables.

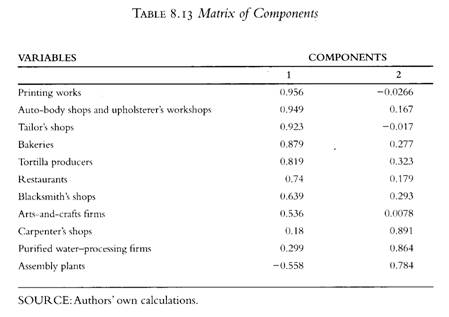

In descending order according to the value of their correlation, the companies that show more correlation in the first vector or component are printing works, auto-body shops and upholsterer's workshops, tailor's shops, bakeries, tortilla producers, restaurants, blacksmith's shops, and arts-and-crafts firms. The companies that show a correlation with the second component are carpenter's shops, purified water-processing firms, and assembly plants (Table 8.13).

By means of the preceding procedure, it was possible to reduce the eleven variables to two. The first, headed by printing works, auto-body shops and upholsterer's workshops, and tailor's shops, is the variable that accounts for the traditional character of Tijuana's industry. The second expresses, from a spatial perspective, the transition to maquiladora-related activities.

After grouping the variables by the method of principal components, indices of the concentration of the companies by colonia (city zone) were constructed in order to (draw a map of concentration by factor (Alegría 1994:425). According to this index, the colonias are grouped into four areas. For the first component, traditional businesses, the colonia with the greatest concentration is the Central Zone, with a value of 44.11. Next is a group of three colonias that present a high concentration: "La Libertad" with 10.97, "La Independencia" with 9.5, and "Nueva Tijuana" with 6.9. Following these is a group of 12 colonias with values ranging from 0 to 5, considered of medium concentration, and another of 59 colonias of low concentration (Figure 8.1).

The component that explains the transitional character of industry in Tijuana is largely concentrated in the "La Libertad" district, with a concentration index value of 19. Next in importance is the Central Zone with a value of 9.89. There is a group of 16 districts of medium concentration (between 0 and 3) and another group of 56 low-concentration (less than 0) districts (Figure 8.2).

The industrial activity that characterizes the group of traditional companies, concentrated in the Central Business Area (CBA), contains elements of intra-urban localization that are different from those of the globalization companies. Among them, printing works, auto-body shops and upholsterer's shops, as well as tailor's shops and bakeries, are notable. Their spatial logic is strongly attracted to the CBA, because of its large number of direct consumers.

Despite the high price of land rent, traditional companies concentrate near the CBA because light manufacturing requires little space for its production and does not use trucks or other vehicles for the transport and handling of merchandise. These small companies remain unaffected by the area's street congestion. And, their activity needs to be near the center of the city because their products are destined for the direct consumer. The reduced space is intensively used and has a high spatial interaction with clients. It is also mixed with activities of the tertiary sector, such as firms ´offices and medical-specialty clinics.

Part of the traditional landscape of Tijuana's CBA, the auto-body shops and upholsterer's shops are influenced by their geographic proximity to the San Diego area and their consumer market is basically the tourism provided by San Diego. As such, they are not involved in the globalizing processes of the urban periphery. Modern industry is moving away from a traditional activity originally explained by its proximity to the San Diego market toward an activity explained also by the global logic of the same vicinity. In its spatial logic, three lines of industry are notable: carpenter's shops, purified water-processing plants, and assembly plants. One would expect a greater concentration of these near the periphery because they require larger spaces for manufacturing and storage, as well as for the movement of heavy vehicles. Unlike traditional industry, they are affected by merchandise transportation routes and street congestion in downtown Tijuana, since their products are sold outside the city, so that the CBA finds itself outside their geographical market boundaries. Nevertheless, because of their transitional character, the elevated price of the CBA does not push them toward sites nearer the city limits, and these industrial plants are older than those established in the industrial parks of the urban periphery.

The "La Libertad" colonia has a spatially strategic location connected with the San Ysidro international border crossing. It was one of the more attractive zones for the first maquiladoras in Tijuana because it is closer to the international crossing than the CBA.

The local or the regional markets are not the focus of the carpenter's shops and assembly plants located in this area, the global markets are due to their transitional nature.

Spatial Distribution of the EAP, by Level of Income

Figure 8.3 shows that the colonias with the largest population of low to medium and low incomes are San Antonio de los Buenos, La Mesa, La Presa, and the eastern part of the Otay Mesa. These zones encircle the urban section of the city, surrounding the sectors where the medium or very high income families live, in the central part of Tijuana. The population distribution in Tijuana's urban space by level of income may also be appreciated by means of another disaggregation of the economically active population into four divisions according to their salary levels: very low, low, medium, and high (Figure 8.4).

The group having a very low income level occupies 19.1 percent of the surface area and is located in the peripheral area. The low-income population forms a ring toward the interior of the city, close to the very low-income population and occupies 24.8 percent of the surface area. The middle-income population shows a more heterogeneous profile in its spatial distribution but tends to be concentrated toward the east of the city, occupying 27.7 percent of the area. Finally, the high-income group covers 22 percent of the area and is located toward the Playas de Tijuana zone and along the Tijuana River.

Demand and Supply of Housing

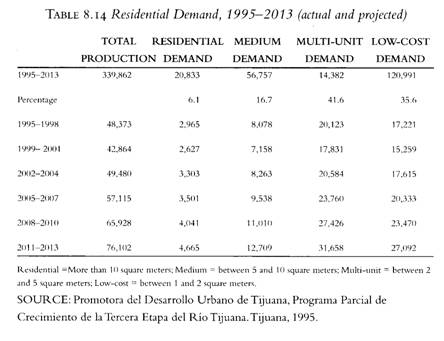

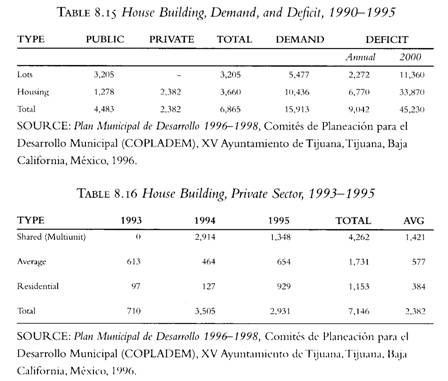

In regards to housing, there is a disparity between production and demand. This problem is pronounced in the case of low- and medium-priced housing (Tables 8.14,8.15, 8. 16).According to estimates by the agency Promotora del Desarrollo Urbano de Tijuana (Urban Development Promotion of Tijuana) (PRODUTSA), the demand for housing between 1995 and 1998 was for 17,221 low-cost units, for 20,123 multi-unit dwellings, and for 8,078 medium-level units. In the agency's projections for the period from 20II to 2013, the demand for multiunit dwellings will be 31,658 and 27,092 for low-cost units. Compared with the high demand for housing in Tijuana and given the high rate of population growth, house building has gone at a slow pace. According to official sources, total housing production during the period from 1990 to 1995 was 6,865 units 4,483 generated by the public sector and 2,382 by the private sector. Since total housing demand rose to 15,913 during the same period, the annual production shows a deficit of 9,042 units per year.

Conclusion

Because of its proximity to California and the constant influx of immigrants to it, Tijuana has become an essential element of (and partner in) the network of global commerce that spans the California-Baja California transborder region. Although this immigration now, in large measure, fulfills the maquiladora industry's need for unskilled laborers, it has been characteristic of Tijuana since its beginnings as a city. Before the inception and flourishing of the maquiladoras, these immigrants were incorporated into the commercial and tourism-related labor market.

Around 1970, the incorporation of immigrants into the labor market occurred in the context of Tijuana's integration into the global network of urban nodes, a process that requires an abundance of unskilled labor for repetitive tasks. It must be emphasized that Tijuana maintains its character as an urban node with California, local in origin and global in recent years. The result is the overlapping of the two. In its local aspect, Tijuana maintains its personality as a provider of light industry services for the tourists who come daily to the CBA or who pass through on their way to the interior of Baja California; upholsterers, mechanics, metal-workers, and artisans are part of the traditional landscape of the CBA. Globally productive processes of high-level technology with companies and products oriented toward the global market also characterize Tijuana today.

The geographic location of Tijuana is not the only explanation for the sociospatial arrangement it has acquired. It is attractive also because of its intense migratory f1ows.Two significant migration periods can be identified: one that goes from Tijuana's foundation up to the 1970s and a second from the 1970s until the present time, when the city started becoming more involved in global commerce, basically in the industrial sector through the maquiladora companies.

From the perspective of population distribution in the urban space, there is a process in which those of high socioeconomic status are more spatially diluted than those of low socioeconomic status. The second, since they are forced to locate on the periphery, where industries are established, cause the place of residence and the workplace to almost overlap spatially. The first follow the real estate market more closely toward the interior of the urban section or in exclusive residential areas distant from concentrated industry.

The San Ysidro border crossing, on the west, gave birth to the city. It is the traditional meeting point between Southern California and the northwest of Mexico. It is also the union of two important urban centers: San Diego and Tijuana. This is the bridge between Tijuana's consumers in San Diego, and San Diego's consumers in Tijuana. Moreover, it is the crossing point, in both senses, for binational families, for binational friendships, and for binational business relationships, and is associated with recreation and relaxation areas on both sides of the border.

The Otay border crossing, east of the city, is fundamentally transnational in character, since it was opened more recently to facilitate the transportation of exports by the maquiladora industry. As such, it is located close to Tijuana's largest industrial zone. Even the recently opened roads on this side of the city are oriented toward this international crossing point. As a consequence, the crossing has not had the same impact on the urban landscape as the San Ysidro crossing. On the U.S. side, there are no important commercial centers close to the international border at the moment, nor residential or recreational areas such as the ones in the San Ysidro crossing. One may well ask what will be the impact of an industrial and commercial development on the U.S. side, on land use, as well as on the levels of socio-spatial segregation on the Mexican side of the Otay border crossing, and on the city in general.

It is also important to note the integration processes of the population to interior and the exterior of the city. Because part of the economically active population is involved in productive activities in California and many of the trips to the other side of the border are made for purposes of consumption indicates, it is clear that there is not a complete integration with the interior of Tijuana.

Another situation involves the workers in maquiladora activities, since, as production processes, in Tijuana they are integrated to global processes disassociated from the interior of the city, from the productive activity point of view. The convergence of the maquiladora industry in Tijuana has practically forced the city to the creation of industrial parks. Nevertheless, since it is necessary for the industries to have easy access to the labor force, on this side of the city spatial proximity between the workplace and the place of residence is a necessity. Consequently, programs for low-cost residential areas in Tijuana's eastern periphery have been created. These consist of lots available to low-income families for house building. These housing areas are adjacent to industrial parks that were created almost simultaneously to these dwellings.

Authors' note: This study was prepared with the financial support of the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC) and Economic Research Associates, Los Angeles, California.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alegría Olazábal, Tito. 1994. "Segregación socioespacial urbana. EI ejemplo de Tijuana."

Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 26,9:2 (May-August), 411-428.

---. 1995. "Reestructuración urbana en la frontera norte de México." In Desarrollo Regional y Urbano: Tendencias y Alternativas, vol. I, edited by José Luis Calva, Adrian Guillermo Aguilar, and Tito Alegría Olazábal, chapter 3. México, D.F.: Instituto de Geografía, UNAM.

Baum, Scott. 1999. "Social Transformations in the Global City: Singapore." Urban Studies 36 (7), J095-III7·

Castells, M., and]. Borja. 1997. Local and Global: The Management of Cities in the Information Age. London: Earthscan Publications.

Choi, Dae Won, and Martin Kenney. 1997. "The Globalization of Korean Industry: Korean Maquiladoras in Mexico." Frontera Norte 9:17 (january/june), 5-22.

Estrella. G. 1998. "Perfil de la población urbana en la frontera norte de México." Comercio Exterior 48:5 (May), 378-383.

Friedman,]. 1986. "The World City Hypothesis." Development and Change, 17:6<)-83.

Garza, Gustavo. 1989. "La política de parques y ciudades industriales en México: etapa de expansión, 1971-1987." In Una década de planeación urbano-regional en México, 1978-1988, coordinated by Gustavo Garza. México: EI Colegio de México.

Garza, Gustavo, and S. Rivera. 1993. "Desarrollo económico y distribución de la población urbana en México, 1960- 1990." Revista Mexicana de Sociología 55: I (January-March), 177212. México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

----. 1995. Dinámica macroeconómica de las ciudades en México, t.I, México: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, EI Colegio de México y la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Granger, M. D. and G. C. Blomquist. 1999. "Evaluating the Influence of Amenities on the Location of Manufacturing Establishments in Urban Areas." Urban Studies 36( I I): 185<)1873·

Hernández Gómez, Emilio. 2001. "Globalización industrial y segregación urbana en Tijuana, Baja California.” Comercio Exterior 51:3 (March),234-242.

Mungaray, Alejandro 1985. "Actividades económicas," In Historia de Tijuana: Semblanza General, coordinated by David Pinera. Tijuana: UNAM-UABC and XI Ayuntamiento de Tijuana. ---. 1997. Organización industrial de redes de subcontratación para pequeñas empresas en la frontera norte de México. México: Nacional Financiera.

Mungaray, Alejandro, and J. Alvarez. 1987. "La oferta de espacios industriales en el desarrollo de Tijuana." FONEP 123 (January), 7-12.

Mungaray, Alejandro, and J. M. Ocegueda-Hernández. 1995. "La nueva frontera norte: Entre la devaluación y la 187." Comercio Exterior 45:6 (June), 450-459.

Pincra, D., and J. Ortiz. 1985. "Panorama de Tijuana 1930-1948." In Historia de Tijuana:

Semblanza General, coordinated by David Piñera. Tijuana: UNAM-UA13C and Xl Ayuntamiento de Tijuana.

Ramírez, R. J. 1983. "La conflictiva zona libre de Baja California." Economía informa 110 (November): 2l)-31.

Reingold, D.A. 1999. "Inner-City Firms and the Employment Problem of the Urban Poor:

Are Poor People Really Excluded from Jobs Located in Their Own Neighborhoods?" Economic Development Quarterly 13(4): 291-306.

Rey, S., Ganster, P, del Castillo, G., Alvarez, J, Shelhammer, K., Clement, N. and Swcedler, A. 1998. "The San Diego-Tijuana Region." In Integrating Cities and Regions: North America Faces Globalization, edited by J.W Wilkie and C. Smith. Guadalajara/Los Angeles:

Universidad de Guadalajara UCLA Program on Mexico, Centro Internacional Lucas Alemán para el Crecimiento Económico.

Ruiz Vargas, Benedicto, and Patricia. Aceves Calderón. 2000. "Pobreza y desigualdad social en Tijuana." El Bordo 2. http://www.tij.uia.mx/elbordo/vol02/contenido.html

San Diego Association of Governments. 1998. Retos y oportunidades derivados del crecimiento de la región fronteriza Tijuana-San Diego. San Diego: Resumen Histórico. http://www. sandag.org

Scott, Allen J. 1993. "Southern California's Pathway to High-Technology Industrial Development, 1920-1960." Technopolis: High-Technology Industry and Regional Development in Southern California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ---. 1996. "The Craft, Fashion, and Cultural-Products Industries of Los Angeles:

Competitive Dynamics and Policy Dilemmas in a Multisectorial Image-Producing Complex." Annals 4 the Association <!f American Geographers 86:2 (June), 306-323. ---. 2000. Regions and the World Economy: T11C Coming Shape of Global Production, Competition, and Political Order. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Scott, Allen J., John Ab'11eW, Edward W Soja, and Michael Storper. 1999. "Global City Regions." Paper presented at Global City-Regions conference. University of California, Los Angeles, October 21-23.

Sassen, Saskia. 1991. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tijuana City Council. 2000. Social and Economic Profile.

Unikel, Luis, C. Ruiz Chiapetto and G. Garza Villarreal. 1976. El desarrollo urbano de México.

Mexico: El Colegio de Mexico.

CONTRIBUTORS

ALEJANDRO MUNGARAY is Chancellor and Associate Professor of Microeconomics and Industrial Organization in the School of Economics and International Relations at the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, where he received his Bachelor's degree in Economics. He earned his Master's and Ph.D. in Economics from the Universidad National Autónoma de Mexico. He did postdoctoral studies in Latin American Economic History at UCLA. He is a member of Mexico's National System of Researchers and the Mexican Academy of Science. His research fields include industrial policy and the development of micro-businesses, regional economic development of the US-Mexico border, and management and innovation in higher education. He is the author and coauthor of 28 books and 38 book chapters, 60 scholarly articles, and 52 articles in various periodicals. He has directed and co-directed 16 research projects funded by national and international sponsors and the publication of 7 issues of international magazines. He has lectured and presented papers at conferences in Mexico and internationally.

SONIA LUGO MORONES graduated with a Bachelor's in Economics and a Master's in International Economics from the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. She earned a Ph.D. degree in Agricultural Economics from the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. A member of CONACYT's National System of Researchers, she has also been the head of the Faculty of Economics and International Relations at Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, president of Mexico's National Association of Economic Teaching and Research and vicepresident of the Latin American Association of Faculties, Schools and Institutions of Economic Research. Her academic experience has been mainly in the areas of international economics, regional economic development and agricultural economics, working as teacher, researcher and thesis advisor. She is the author and co-author of many scholarly books and articles.

NOEARON FUENTES is a professor and researcher in the Department of Economic Studies at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, where he was director from 2000 to 2003, director of Graduate Studies, and director of the Master's program in Regional Development. A level-2 member of CONACYT's National System of Researchers, he received a Ph.D. degree in Economics and a Master's in Mathematical Behavior Science. He also has a Master's in Economics from the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México and a Bachelor's in Economics from the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo Leon. With Sonia Lugo and Mario A. Herrera, he co-authored Matriz de lnsumo-Producto para Baja California: Un Enfoque Hibrido (México: Universidad Autónoma de Baja California/M.A. Porrua, 2004); with Alejandro Díaz-Bautista and Sarah Martínez Pellegrini, he edited Crecimiento con Convergencia 0 Divergencia en las Regiones de México:

Asimetría Centro Periferia (México, D.F. : El Colegio de la Frontera Norte/Plaza y Valdés, 2003); and he was the author of Matrices de Insumo-Producto de los Estados Fronterizos del Norte de México (Baja California Norte, México: Universidad Autónoma de Baja California/Plaza y Valdés). His articles have been published in Problemas del Desarrollo, Comercio Exterior, and Revista Mexicana de Economía y Finanzas. In recent years, he has worked on the application of input-output models in the northern border region of Mexico, with the support of the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California and the Government of the State of Baja California. The results of his research were the academic basis for the recently approved Law of Competitiveness and Economic Promotion passed by the Congress of the State of Baja California.

CUAUHTEMOC CALDERON VILLARREAL is a full-time researcher for the Department of Economic Studies at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. A level- 2 member of CONACYT's National System of Researchers and a member of CONACYT's National System of Evaluators, he is also an associate researcher of the Faculty of Law, Economics and Management's Laboratoire d'Economie d'Orleans (CNRS' mixed research unit no. 6586) at L'Universite d'Orleans and an associate researcher of the Centre d'Etudes en Macroeconomic et Finances Internationales at the Universite de Nice Sophia Antipolis. He graduated from the Universite de Nice Sophia Antipolis with a Ph.D. degree in Economic Sciences. He was awarded both the Paris Medal and the Palmares for the best economic sciences doctoral thesis of 1995. He was a Fulbright Visiting Professor in Border Economics Research and Instruction at the University of Texas, El Paso. He was the creator and founder of the Master's Program in Economic Sciences at the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juarez. From 2000 to 2004, he was the director of the ANUIES-ECOSNORD Moo-H02 research project called "Los efectos de las politicas de liberalizacion de los intercambios sobre las inversiones extranjeras directas y las nuevas formas de cooperacion industrial." He is the author of articles published in international journals, and co-author, with Thomas M. Fullerton,Jr., of Infiationary Studies for Latin America (Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua:

Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez and Texas Western Press, 2000).

ALEJANDRO DIAZ-BAUTISTA is a professor and a researcher in the Department of Economic Studies at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, where is also the head of the Master's Program in Applied Economics and has taught courses in the fields of macroeconomics, international economics, political economy, econometrics, public finance, the economy and territory, regional economics and industrial organization, among others. He received his Master's and Ph.D. in Economics from the University of California, Irvine. He graduated from the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de Mexico with a Bachelor's degree in Economics. Since 1999, he has also been teaching at the Universidad Iberoamericana del Noroeste. At the professional level, he worked for the Ministry of Energy and the Regulatory Energy Commission, where he served as head of the Department of Economic Analysis. He has written various books and his articles have been published in scholarly journals both at the national and international levels. His book Los Determinantes Del Crecimiento Económico: Comercio Internacional, Convergencia y Las Instituciones (México, D.F : El Colegio de la Frontera Norte/ Plaza y Valdés, 2003) was recognized by the European Union Publishers Forum as part of the European Union Catalogue of Key Publications. He has lectured and given presentations in the United States, Canada, Europe, Asia, Australia, and Mexico. A member of Mexico's National System of Researchers, he has dedicated many years to research in the fields of international economics, industrial organization, and economic growth.

CESAR MARIO FUENTES received his Ph.D. in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Southern California and his Master's in Regional Development from El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, where he has been a researcher since 1990. A level-I member of Mexico's National System of Reseachers, he has written many scholarly articles and book chapters related to U.S.-Mexico border issues. He edited with Sergio Pena Medina Planeación binational y cooperación transfronteriza entre México y Estados Unidos (Ciudad Juárez: Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad de Juárez and Tijuana: Colegio de la Frontera Norte). He has taught courses at the Master's level at the Colegio de la Frontera Norte, University of Texas at El Paso, and the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad de Juarez, as well as has directing 10 master's theses (one of which won the first prize of the 2002 Public Administration State Awards in Sonora) and 2 doctoral theses. He has participated in more than 30 conferences in Mexico, the United States, and Canada.

EMILIO HERNANDEZ received his Bachelor's in Economics, his Master's in Urban Development and his Ph.D. in Economic Sciences from the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, where he has been Associate Professor in the School of Economics and International Relations for 16 years. A level- I member of Mexico's National System of Researchers (SNI) and a PROMEP professor, he is also an evaluator in the accreditation of Economic Science teaching programs. He teaches economic geography, regional development, statistics and research methodology at the undergraduate and graduate levels. His research is concentrated in the topics of globalization, urban and industrial expansion, and social segregation. He is a member of the editorial board of UABC's journal Estudios Fronterizos and of Social Perspectives /Perspectivas Sociales, edited by the Schools of Social Work at the Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, University of Texas at Austin, and University of Texas at Arlington.

SÁRAH MARTINEZ PELLÉGRINI is a professor and researcher at EI Colegio de la Frontera Norte, where she has been Head of the Regional Office in Mexicali, Director of Graduate Studies, Head of the Department of Public Administration Studies, and General Director of Academic Studies. She obtained her Bachelor's in Economic and Managerial Sciences in the field of regional and urban development, a Master's in Environmental Management, and a Ph.D. in Economic Sciences from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. As an Erasmus Programme student, she did professional studies at the University of Sussex, England. She also holds a certificate in Local Development from the International Labor Organization. She has written articles in the areas of economic integration, regional development and public administration, which have been published in journals and book chapters.

JORGE EDUARDO MENDOZA is the Head of the Department of Economic Studies and was coordinator of the Master's Program in Applied Economics at EI Colegio de la Frontera Norte. His academic coursework includes teaching graduate-level regional economics, economic growth, and labor economics, both at Colef and at San Diego State University. A level-2 member of Mexico's National System of Researchers, he has also published articles related to regional economic analysis and the impact of the U.S.-Mexico economic integration on the economic growth of Mexico's northern border region in journals published in Mexico, the United States, and Europe.

JUAN M. OCEGUEDA-HERNANDEZ is Professor of Macroeconomics and Economic Development in the Faculty of Economics and International Relations at the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. He received a Ph.D. in Economics from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico and is a member of CONACYT's National System of Researchers. As an author and co-author, he has published 6 books, 9 book chapters, and IS journal articles in subjects related to economic growth, regional development, and economics of education.

MARTIN RAMIREZ-URQUIDY is Associate Professor of Microeconomics and Industrial Organization and Institutions in the School of Economics and International Relations at the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, where he also received a Bachelor's in Economics. He has received Master's degrees in Economics from California State Polytechnic University and Claremont Graduate University, where he is now working on a Ph.D. in Economics. The author and co-author of articles on small businesses, institutions, and industrial development, he recently received a CONACYT scholarship to support his doctoral studies.

Sociospatial segregation is the differentiation of individuals by homogeneous residential areas, according to their social status.

Copyright © 2006 - 2009 PROFMEX. All rights reserved |