Mexico and the World

Vol. 11, No 1 (Summer 2006)

http://profmex.org/mexicoandtheworld/volume11/1winter06/chapter7.html

CHAPTER SEVEN

Production Efficiency and Credit Availability

for Micro and Small Firms in Baja California

Alejandro Mungaray

Martin Ramirez-Urquidy

THE STATE OF BAJA CALIFORNIA receives constant flows of foreign investment in the form of maquiladora industry. Historically, the maquiladora industry has grown in the region stimulated by its nearness to California and by the low wages in Mexico. The benefits from foreign investment in the region, however, have not achieved their potentially high levels. The maquiladora industry in Baja California generates a large number of low-paid jobs and few managerial positions for Mexican professionals. Local smaller firms contribute only a small share of local inputs in the production of the large exporters. Thus, local firms experience only a modest impact from the maquiladora dynamism. The poor incorporation of local inputs in the production of large foreign firms can be attributed to the precarious competitiveness of local small firms. It is also a consequence of the absence of long-term institutional efforts oriented toward fostering the productive linkages between multinational firms and small firms through a regional industrial policy, and toward stimulating the formation and growth of small firms. These factors have contributed to the low multiplier impact derived from foreign investment.

The development of small firms has been negatively affected by the structural reforms implemented since the 1980s. Macroeconomic stabilization and economic liberalization have created an adverse environment for the growth of small firms. Combating inflation has meant reducing monetary stock and increasing interest rates, thus reducing credit availability for small firms. Small firms have had difficulty adapting to the new environment of liberalization and lack of financing. Many small firms have either gone out of the market or performed poorly, whereas large firms have strengthened their adaptation possibilities through financing in the international capital markets.

Research on the importance of small firms has appeared recently. The economic literature about small firms during a large part of the twentieth century minimized their importance in the economic structure, and even suggested that their insignificant role would decline. These conceptions were strongly supported by the productive and technological superiority of large firms. The underestimation of the role played by small firms has been challenged. Evidence from the 19805 suggests that the importance of small firms has increased significantly, which has stimulated the emergence of small firm studies in economics. Such research attempts to explain the determinants of the formation, expansion, and dissolution of small firms and the dynamic relationships between small firms, markets, macroeconomic variables and economic development (Acs 1992:40).

The enlargement of the small firms sector is important because of the potential of such enterprises to expand employment and generate economic development owing to their labor-intensive productive processes. (Acs and Audretsch ]990:17), which offers great possibilities for developing countries. Creating small firms is a feasible way to increase income, particularly of the poor, because these firms require low investment. Diverse analytical perspectives have shown that countries with a generalized presence of prosperous micro and small firms, enjoy more equal income distribution than those having less and larger firms (Harper 1984:19). In addition, a stronger micro and small firms (MSF) sector in developing countries can strengthen domestic demand through consumption linkages (Yamamoto ]959:83), reduce external imbalances through efficient import substitution, and expand the country's growth potential (Ruiz and Zubiran ]991). Small firm expansion and prosperity are important for macroeconomic stability since they constitute a constant flow of business opportunities and innovations that help to avoid the adversities of the business cycle (Carlsson 1999: 107).

Small firms can be defined quantitatively or qualitatively. The first defines small firms in relation to the number of workers, the capital value or the value-added output. The second defines the firm in relation to its internal organization and management. According to the definition of the Secretaría de Comercio y Fomento Industrial (Ministry of Commerce and Industrial Promotion) (SECOFI), micro firms have between I and 30 workers and small firms employ between 31 and 100 workers.

This study first tests whether the availability of financing is associated with greater efficiency. Credit availability facilitates the purchase of better inputs, machinery, and technologies, with the result of a greater efficiency. If this statement is empirically supported, then we can say that macroeconomic stabilization using tight monetary policy is associated with the poor performance of small firms and their inability to adapt. A policy of selectively extending credit to micro and small firms under these circumstances would promote their efficiency and their contribution to development. If the statement is not empirically supported, then we must conclude that the credit policy by itself is not capable of contributing to the expansion of small firms and should be preceded by other types of institutional support and incentives.

The study also attempts to explain the production structure of the MSF of the sample in order to analyze their degree of efficiency, factor intensity, and factor substitution possibility. The characteristics of the MSF in the sample and those suggested by the literature is compared and contrasted. We would expect that micro firms exhibit relatively less efficient productive processes, lower intensity of capital utilization, and more difficult factor substitution than small firms do.

The Cobb-Douglas (CD) and the Constant Elasticity of Substitution (CES) production functions are estimated in order to carry out the analysis. CD and CES are estimated separately for the firms using resources from the banking system and for those facing financial constraints in order to test the impact of credit availability on productive efficiency. The analytical parameter defining productive efficiency is the degree of homogeneity of the production functions, which defines the returns to scale. Factor intensity is estimated through both the CD and CES production functions. Since the CD assumes unitary elasticity of substitution, this analytical parameter is estimated through the CES production function.

The data analyzed were obtained in 1998 through interviews of managers and owners of 67 MSF in the metal products and food and drinks manufacturing industries in Baja California. These two industries represent more than 50 percent of the firms, almost 70 percent of the total employment, and 70 percent of the value added in the manufacturing sector. They are especially important because they account for more than 90 percent of MSF. The interviews took place between June and September 1999.

Thereafter we discuss the macroeconomic stabilization process followed by the Mexican economy and its negative impact on small firm development through tight monetary policy and credit constraints. Then we address the international framework in which the importance of the small firms development has emerged. The role played by small firms in the regional industrial organization is critical in determining the competitiveness of the region in a global context. The discussion summarizes the development of the industrial structure and highlights the importance of the two industrial branches considered here.

The theoretical perspective supporting small firms' development is then explained, highlighting the advantages small firms offer to industrial organization and the and the benefits a production system that links large firms with small firms may bring to industrial competitiveness and development. We also present a theoretical discussion on production function focusing especially on the economies of scale and factor substitution possibilities, as well as the innovation and technological potential of small firms compared with that of large firms.

Then we'll discuss the specifications, variables, analytical parameters, and data sources of the CD and CES models, as well as assessing the results of the two models. Based on the empirical findings, the concluding remarks examine possible institutional policies for micro firm development in the context of social and regional development.

Credit Availability for Large Firms and Small Firms under the Structural Reforms and Macroeconomic Stabilization

Mexico introduced structural reforms beginning in 1989 to reduce and stabilize inflation, recover growth, and return to voluntary foreign sources of capital (Aspe 1993). The government-initiated negotiations to reduce external debt in order to diminish its impact on economic growth and to obtain new resources to finance export projects. Reforms implemented included monetary, financial, fiscal and trade policies.

Monetary policy was oriented toward the reduction of inflation, the stabilization of the exchange rate, and the attraction of financial flows. Thus, the Central Bank authority decided to tighten the monetary policy in order to depress aggregate demand and avoid inflationary pressures. The rise of the domestic interest rate stimulated inflows of foreign capital and overvalued the real exchange rate. Thus, reduction of inflationary pressures was guaranteed by establishing high interest rates that depressed aggregate demand but overvaluated the exchange rate, which enabled the purchase of foreign goods and inputs at low prices.

Financial policies focused on improving the financial system in order to stimulate savings and promote the best allocation of savings through credit extension. The financial measures implemented included the creation of new and more sophisticated financial instruments, the improvement of service quality in bank branches, and the penetration in more markets, including low-income clients. The banking system was permitted to set interest rates and allocate resources depending on conditions and goals. The Central Bank replaced reserve requirements for open market operations through Certificados de la Tesoreria de la Federacion [Mexican Federal Treasury Bills] (CETES) in order to manage monetary policy. The Constitution and some regulations were amended. The banking system was returned to the private sector via an authorization act (not a charter) after almost a decade in government hands. Regulations permitted the merging of financial institutions to form financial groups in order to achieve economics of scope and scale. Finally, stock and money markets were transformed to attract foreign financial flows and finance private and government investment. The liberalization of the financial markets and the constitutional amendment on property rights and foreign investment helped attract external resources to complement the availability of financial resources for private sector development.

Fiscal policy stipulated the income tax rate be reduced from 35 to 50 percent down to from 35 to 42 percent and the creation of new taxes, such as those on foreign investment profits and company assets in order to strengthen the public budget. The sales tax rate was reduced from 15 to IO percent. Finally, fiscal authorities attempted to enlarge the tax base in order to increase fiscal resources.

In 1986 when Mexico joined the General Agreement on Tariff, and Trade (GATT), trade policy began to be oriented toward opening the economy to foreign goods and a reduction was made in the maximum tariff from IOO percent to 20 percent and import quotas were abandoned. Later, in 1993, Mexico joined the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Finally, reforms were made in the regulations related to foreign investment. Before 1989, foreign investors could own no more than 49 percent of a firm's shares in nonstrategic sectors. Currently, foreign investment can own IOO percent of the total shares of firms considered nonstrategic. Strategic sectors include oil, electricity, finance, rail, telecommunications, and broadcasting services (access to these sectors was restricted to the State or Mexican individuals). After the 1995 crisis some strategic sectors were opened to foreign investment. Foreign investors can control more than 51 percent of total shares in all sectors of the economy, except in oil and electricity. These modifications were viewed positively in foreign and domestic capitals.

As a consequence of the structural reforms and stabilization policies, inflation was reduced from 120 percent in 1988 to IO percent in 1993. Manufacturing became the most important sector of the economy, the export sector grew as never before, and the money and capital markets attracted huge amounts of capital to finance the investment of the productive and government sectors.

Macroeconomic stabilization through market liberalization and structural reforms promoted by the neoclassical theorists is thought to generate conditions propitious for investment and growth. Therefore, international financial institutions have advised the governments of developing countries to implement these policies in order for them to access the financial resources of international or private financial institutions (Taylor 1988) to generate the conditions for growth and to alleviate the deep poverty of large parts of their population. However, some heterodox theorists are critical of those who see market liberalization as the cornerstone of growth and income equality. The institutional economics view suggests that the economic reforms oriented toward the promotion of free-market movement are not sufficient to allow economies to achieve economic growth and higher welfare. This perspective suggests that markets fail very often, affecting the economic agents in various degrees. Therefore, market reforms such as liberalization should be accompanied by institutional reforms to allow each economic agent to adapt to the new economic environment (Williamson 1995:218). Markets are thought to be fair since they provide the same incentives for all. But these incentives are the same for different economic agents. Thus markets are not so fair since the economic agents with the best adaptation ability are better able to take advantage of the incentives than those with poorer adaptation capability.

Market reforms and macroeconomic stabilization in Mexico have created the conditions for growth. In fact, the Mexican economy has shown stable growth and outstanding export dynamism since the main reforms were established. The structural reforms also allowed the economy to attract financial flows to encourage private and public investment and to facilitate macroeconomic stabilization by avoiding sharp disturbances in the exchange rate. However, the stabilization process lowers the activities of the economic agents linked to the domestic market dynamics since it requires tight monetary policy through credit constraint. The monetary mechanism by which the authorities are able to lower aggregate demand produces differential responses of the productive units. According to Mark Gertler and Simon Gilchrist, the "small firms are more sensitive than large firms to macroeconomic conditions. Macroeconomic conditions include both the state of the business cycle and the state of the stance of monetary policy" (1991:2).

An economy like Mexico's, with a low rate of domestic savings, must attract significant foreign savings through money and capital markets. Tightening monetary policy through increases in domestic savings is fundamental to creating a significant gap between domestic and external interest rates in order to attract foreign investors.

A rise in the domestic interest rate affects small firms more than large firms. The former are tied to the monetary aggregates associated with the performance of the banking system, and traditionally their financing resources come from domestic banks. Bank loans are subject to higher interest rates since these interest rates depend on the bank's financial position as well as the client's profitability prospectus. Banks assume small firms have a higher risk and that they offer lower collateral than larger firms. Credit is either denied or more expensive for small firms, assuming risk-averse behavior of the intermediaries (Bernanke and Gertler 1987). Thus, bank financing under macroeconomic stabilization in developing countries is expensive when compared to financing alternatives available to large firms. In contrast, the performance of large firms is tied closely to the monetary aggregate linked to money and capital market performance. Thus, interest rate movements of commercial paper and government bills are associated more with large firms since they are able to finance in open market operations (Gertler and Gilchrist 1991:35).

Macroeconomic stabilization in Mexico has brought credit constraints for the majority of smaller firms, which depend on bank financing, and has facilitated the attraction of foreign capital (large and influential firms) through open market operations. Thus, the adaptation process against the predator foreign competition of trade liberalization has been significantly easier for large firms than for small firms. Small firm development in many cases has been obstructed either by the lack of credit or by the high cost of bank financing.

Finances operate as a constraint when firms can only increase sales if they could have financed the required marketing effort and the extra working capital necessary to finance additional stocks and debtors. Many small firms simply operate with very little financing and their expenditures and expansion are tied to their cash flow. Finances also operate as a constraint since product development has to be slow because of the lack of financing or where cost of productivity and competitiveness development should be consigned to other parts of the firm (Pratten 1991: 108). The financial needs of many of the small firms in Mexico are confronted with the firms' cash flow, informal credit extensions, informal speculators, or resources provided by relatives.

Access to credit allows firms to have a higher degree of efficiency and competitiveness. Credit allows them access to better production, markets, or management techniques that put the firms in a better position against competitors. Thus, firms can purchase better machines and tools and develop human capital. Access to financing may not, however, be associated with higher degrees of efficiency where managers do utilize resources efficiently. Credit extension alone under these conditions can put the future of small firms in danger because of the unproductive use of the credits and the unavoidable payback (Hulme 2000:26).

Industrial Development and Small Firms in Baja California

There are signs of deep industrial reorganization internationally. Since the second half of the 1970s, the leading economies have operated at a slower pace. Overcoming a period of recession meant industrial conversion during the 1980s and 1990S, which has generated precarious social conditions, unemployment, and social inequalities. Some national economies and even some regional areas have resisted the recession of the world economy and some have even experienced growth in output and employment.

A common characteristic of some of these regions is the interaction between the community and firms with converging interests. This features the industrial districts which group a large number of firms, especially MSF, connected with each other at different stages of the production of a homogeneous good. This good can be an input in the production processes of larger firms oriented to domestic or international markets (Pyke and Sengenberger 1990:2). Other resistant regions have a large number of international firms, some of them connected to small local firms, which export to markets in free trade blocs (0hmae 1995: 5). Both cases present economic, social, and political interactions which depend on the community's social and institutional organization.

The successful experience in terms of growth and employment observed in certain regions of Europe, the U.S., and Asia since the 19805 should catch the attention of policymakers and analysts. Although these countries, and even their regions, have different social contexts, firms, and organization, they were able to restrain global competition, characterized by changing demand, productive flexibility, and market specialization. These experiences may provide answers to two questions: (1) how to stimulate employment and the income potential of the small firms and (2) what are the institutional framework and industrial policy in which the less favored small firms can be part of a successful regional development based on technology innovation. A national approach should be followed to answer these questions. Since regional industrial reorganization is taking place in an international context, this perspective should take into account the integration processes among economies and the formation of trade blocs. It is also necessary to redesign the role of social, economic, and political institutions, regional, national, and international firms, and national, local, and regional governments in the learning processes required by the industrial organization for development (North 1990:16).

There are two predominant firm models in the context of integration: the classic large firm based on standardized output, automatization, and vertical organization that achieves economies of scale and significant levels of competitiveness; and the lean production system, based on an industrial organization associated with a systematic view of the firm. This system is capable of eliminating the costs derived from the small scale of the firms and the consumer preference rigidities. The lean system features competitiveness based on a quick response to consumers' changing needs, a more diversified supply to satisfy consumer demands and process and product design technologies (Nonaka 1991:96-97).

Technological advances have allowed for a reduction of the optimal production scale. Organizational advances have allowed the spread of integration and cooperation as common practice in some regional economies. Both elements have fostered increasing participation of regional small firms in global productive processes, combining large-scale and flexible production strategies. Such a combination is essential in order to satisfy the massive and differentiated markets of integrated economies.

In developing countries, supporting small firms can help minimize the social costs of unemployment caused by the adverse effects of the predatory industrial competition in the globalization context. The special dynamism shown by the border states of northern Mexico in recent decades has prompted discussions about the role of economic liberalization in creating the conditions for growth. Attention has focused also on the importance of forming vigorous regions in the countries as essential elements for a steady growth in the globalization context.

The lack of linkages to the most important production and distribution areas located in the central part of Mexico left the border states in the north with no possibilities for economic growth or any expectations for prosperity. The federal government created "Free Zones" to foster development and an open economy-in contrast to the strict protectionism for industry in the rest of the country. Thus, the region offered advantages for investment unlike any other area in Mexico. Free flow of imports and this fiscal stimulus promoted foreign investment in maquiladora industries. The maquiladoras were allowed to bring their inputs from abroad and people were allowed to import consumption goods. Industrialization via maquiladora formed strong productive and consumption linkages. The combination of Mexican creativity, a practical industrial culture, and entrepreneurial learning transferred from the U.S. created a vast sector of Mexican small businesses in the area. Many of these initiated their industrial experience by working for foreign capital maquiladoras. Thus, in 1993 Mexico's northern border states were home to 8.2 percent of industrial firms and 14 percent of small firms in the country.

There is no doubt that the institutional incentives implemented by the government in the northern border states developed what is the most dynamic region in Mexico today: the state of Baja California. Baja California has a large part of the maquiladora industry of the country and receives an important share of the new flows of foreign investment. Thus, it is the fastest growing region in Mexico and has the lowest unemployment rate (less than 3 percent).

Disaggregating the Baja California industrial structure into industrial branches shows two important tendencies. The first is the food and drink branch (31). The output of this branch is directly related to population dynamics but inversely related to income (Mungaray 1992:71). Thus, the food and drink branch offers easy entry for new firms and has the largest number of firms. The fact that the number of food and drink firms increased while employment participation decreased from 36 percent to [4 percent and the branch's share in manufacturing value added fell from 40 percent to 23 percent is directly associated with the growth of MSF during the period from 1988 to 1993. The MSF share of total manufacturing firms increased from 96 percent to 97 percent; employment in the MSF rose from 36 percent to 45 percent; and manufacturing value added of the MSF rose from 18 and 28 percent (Ruiz Durán 1993:525).

The second trend relates to the consolidation of the activities in the metal products, machinery and equipment, and precision surgical instruments branch (38). Branch 38 has the second largest number of manufacturing firms, 24 percent in 1993. It has increased its share in employment and value-added output from 49 percent to 52 percent and 35 percent to 43 percent, respectively, from 1988 to 1993. This branch's expansion is related to demand for inputs and equipment in the various sectors of industrial activity. The small decrease in the number of firms in this branch is associated with the decline of MSF participation from 86 percent to 77 percent. Whereas the number of MSF fell, their share in the branch value added increased from 16 to 17 percent.

Previous regression analysis applied to aggregate data and to those of small firms in Baja California in the periods from 1985 to 1989 and from 1989 to 1993 (Mungaray 1997: 57) shows interesting results. First, growth of industrial firms in Baja California is explained in large part by the growth of MSF. The R2 for the periods from 1985 to 1989 and 1989 to 1993 was 0.72 and 0.88 respectively. The number of MSF also explains the generation of employment in the industrial sector. The R2 for those periods jumped from 0.11 to 0.61, respectively. In contrast, industrial value-added output decreased, which could be explained by the behavior of the value added by the MSF in the same periods. The R2 was 0.24 and 0.14 respectively for the periods from 1985 to 1988 and from 1989 to 1993. The R2 indicates not only the important contribution of MSF in the growth of industrial firms and employment but also their low and decreasing participation in the dynamics of industrial value added. Thus, we may conclude that the vulnerability of MSF has increased over time, since they represent the largest share in terms of the number of firms and employment, but they have the smallest participation in value-added output.

We can consider two large groups of manufacturing branches that exhibit different trends: one group consists of branches 31 and 38. They are the most important in terms of value-added output, employment, and number of MSF. The second group includes nonbasic minerals (branch 36), chemical products (branch 35) and wood and wood products (branch 33). These branches have begun to show increasing importance in the economic structure of Baja California in terms of employment, productivity, and number of firms.

The existence of these two groups of manufacturing activities raises the difficult question about where to allocate scarce resources among the different sectors. If the market were to assign such resources, then production activities showing growth-such as branches 33, 35, and 36-would be supported. If the objective is to encourage social development and the distribution of income, then branches 31 and 38 should be the priority. Our approach favors the impact on social development derived from a regional industrial policy; this study, therefore, analyzes the productive structure of MSF in branches 31 and 38.

Production Function, Small Firms, and Economic Development

ECONOMIES OF SCALE AND ECONOMIC ORGANIZATION

The production function describes the relation between any specific group of factors and the maximum amount of output that can be achieved (Blair and Kenny 1984:74). Henderson and Quandt (1980:66) indicate that the combination of factors in the production of any good suggests a technical problem. It becomes an economic problem when the objective is finding the best combination according to the market prices of factors. The best combination is one that minimizes production costs. As a consequence, the neoclassical production function view of the firm with a hierarchical structure (Williamson 1990: XVII) indicates that a larger scale, because of a technical change, reduces the factor substitution possibilities (Stewart and James 1982:4). According to this view, any substitution of capital for labor that modifies the production function faces technological and organizational rigidities.

Returns to scale decrease when production changes are less than proportional compared with the factor changes and increase when production changes are more than proportional compared with the factor changes. Increasing returns to scale is a consequence of capital and labor specialization associated with the large scale (Pappas and Brigham 1985:219-221). Neoclassical theory has concluded that scale economies require the production function to exhibit increasing returns to scale (Cohn 1992: 12 3). This suggests necessarily the existence of grand scale production and a large market size (Krugman 1993:21).

Uncertainty and risk increase in relation to the number of economic agents involved in transactions and in relation to the level of technology and learning sophistication. In the presence of such conditions, the importance of transaction costs among the economic agents increases because of the impact of the search costs, financial costs, property rights and commercialization on both clients and suppliers. As a consequence, a flexible reorganization of the firms becomes an efficient way to deal with uncertainty and risk (Pratten 1991:7).

The institutional theoretical framework suggests that the presence of transaction costs tends to deteriorate large scale economies. This situation makes collective action fundamental (Datta and Nugent 1989:49-50). Flexible reorganization of firms represents a kind of collective action. It is possible only under the presence of propitious formal and informal institutions that regulate the integration of firms. Such institutions govern the ways that economic agents can cooperate and compete (Williamson 1995: 174). As a consequence firms participate in agreements designed to minimize transaction costs in order to achieve economies of scale. Many of the transactions required by firms are more efficient if done internally rather than in the market (Pratten 1991:5).

The relationship between market and firm has two aspects. The first emerges when an administrative process in the firm substitutes exchanges in the market. This suggests that the transaction costs originated by an unarticulated market affecting the potential economies of scale are minimized (or avoided) by the firm's internal organization. Contrary to the neoclassical approach, the production function under these circumstances will be characterized by the search for transaction cost reduction, not by the search for competitiveness through technology (Pratten I991:9).

The second aspect emerges when a process of intermediation in the market substitutes the exchanges mediated by internal administrative processes. Coase would point out that the decision to resort to the market occurs when the costs of organizing an additional transaction in the firm equal the costs of doing the same transaction in the market or organizing it in another firm (I937:395).

The market failure originated under oligopoly competition increases the firm's transaction costs. This directs the firm toward vertical integration in the search for economies of scale. However, the firm tends to integrate horizontally when the failures from the internal large-size organization put operation costs above the returns derived from its production function.

Taking advantage of small-scale features derived from vertical or horizontal integration between firms constitutes an alternative way of promoting the emergence of small firms. Integration under these types of organizations is able to promote small firms and social development by providing a stable source of demand in which small firms can learn, improve themselves, and grow.

SMALL SCALE VERSUS LARGE SCALE

Returns to scale are a measure of the efficient use of factors in the production process. The economies of scale are a measure of the evolution of long-run average costs. Thus, the technological differences between large and small firms generate differences in innovation, productivity, and pricing. The competitive structure emerging from the difference in efficiency between large and small firms includes two key aspects. The first is related to labor productivity, derived from specialization, the second to the average cost reduction because of economies of scale. Both elements constitute a strong entry barrier for small firms leading to industrial concentration. Large firms fix prices through market mechanisms leaving the small firms to play a subordinate economic and political role in the industrial structure (Archibugi et al. 1991:301). Large firms not only attempt to maximize profits but also fix prices in oligopoly markets. Neoclassical theory has insisted that labor productivity in large firms is higher than in small ones because workers in large firms are more specialized than workers in small firms. The basis of this idea is that workers in small firms do as many tasks as required by their production process, and workers do not achieve any degree of specialization. The technology is different in large and small firms as well. Large-scale production allows the optimal use of specialized equipment, whereas the lean production processes of small firms use more versatile but more inefficient machinery. Similarly, large-scale operations motivate big input purchases with discounts that reduce the costs. This applies also for the capital markets because big companies have easier access and lower and preferential interest rates (Pappas and Brigham 1985:296). Therefore, research is yet to be done on the small firm whose contribution to the innovation process has been considered marginal. Work has concentrated on oligopoly companies because "they have maintained ability to perpetuate its technological advantages through their pricing power" (Storper 1985: 264). This implies that the long-term corporate planning of these companies is oriented toward the perpetuation of hierarchies over the small ones.

Technological change implies the solution of a problem related to cost and market change. As a consequence, each new technological paradigm tries to avoid diminishing returns through innovation (Dosi 1988: 1130). This means that innovation in the oligopoly firm originates in the need to avoid the inefficiencies derived from large size and inflexibility. Innovation is also oriented toward compensating for the competitiveness lost to other oligopoly companies with more efficient practices and toward obstructing entry of new medium- and small-sized companies through widening the technological gap. These practices have been questioned in terms of the technology efficiency associated with the mass production system since it does not provide innovation flexibility, fast response to market changes or stimulus for development of new high-tech products or old products with new processes (Hayes and Pisano 1994).

The technological vision of the neoclassical company tends to stimulate processes of predatory competition which lead to an oligopoly industrial organization. Under this market structure, competition among the few large companies that control innovation and technical change together with the uncertainty and the necessity of' staying in the market, moves toward the incorporation of product diversification strategies. This explains why research and development favor product innovation rather than process innovation in order to control consumer preferences. Such a practice accentuates the pattern of industrial organization around large companies (Inaba 1960:21).

Recognizing the economy as an atmosphere of uncertainty (Nonaka 1991: 96; Obrinsky 1983: 75), Japanese companies developed flexible outlines of industrial organization based on the application of scientific knowledge to production processes. Today these systems are known as systems of lean production. Lean production systems have allowed Japanese firms to take advantage of certain market segments having profit opportunities. As a consequence, just-in-time delivery systems and flexible mechanization have created organizational possibilities in which companies of diverse sizes are able to interact. Such interaction can help to overcome the logic of individual productivity as a scale function and to allow the social utilization of automated production processes to stimulate collective efficiency (Storper 1985:272).

The organizational nature of the system makes the difference. Human capital investment and constant training is fundamental. It is based on the formation of teams of workers with multiple skills and abilities at all levels of the organization. Teams guarantee quality, productive flexibility, and innovation. This approach, developed initially in Japan, does not consider labor as a fixed cost but as an asset to be developed. This kind of organization modifies production function. Now the production function includes all the system of large and small firms. It requires high capital investment to produce large amounts of output segmented in small lots of a great variety of products elaborated by the network of companies. This industrial organization takes advantage of the flexibility resulting of high technology and the functional organization of networks linking big and small companies. It also allows the movement from one production process to another depending on the market signals. This reduces the optimal scale of production to a quarter of that required in the mass production system (Ruiz and Kagami 1993:3). Thus, collaboration and entrepreneurship are a necessary condition of the lean production system.

INDUSTRIAL RESTRUCTURING, TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION, AND SMALL FIRMS

Firms in most industries have searched for scale economies for decades. This kind of production system had two consequences in the production organization: (I) the additional costs of expanding the companies were almost insignificant in spite of the bureaucratic, inflexible, and wasteful organization; and (2) the association of large companies with efficiency was accepted without discussion (Economist 1993:13). The Schumpeterian hypothesis of a positive relationship between innovation and oligopoly power and the notion that large companies are more innovative than small ones caused the minimization of the role played by small firms in the innovation process and economic growth.

The recessive atmosphere that motivated the industrial restructuring of the 1980s and 1990S has stimulated an innovative process with important consequences for productivity and employment. However, the innovative changes of the large companies attempting to substitute labor for capital have exacerbated industrial unemployment. In the first case, it is clear that the incorporation of technical progress to increase the productivity of large companies has reduced the number of jobs in the economy (Sylos Labini 1993: 19, 63). In the second case, the expansion of new technologies around the world, together with the fall of commercial barriers, the liberalization of financial markets and the international convergence of consumption habits, has opened new business opportunities to thousands of competitive small- and medium-sized companies. This fact has increased the potential of these firms to contribute to regional development because they are able to take advantage of the demand from large firms. The emergence of small firms cooperating with large firms can provide more jobs than any other source and can increase the growth potential of regions and countries.

Industries have moved from heavy industries toward high-tech services in the U.S. since the beginning of the 1990s. Firm size has decreased since the optimal scale has been reduced as a result of technical and organizational innovations. Traditionally large auto and electronic firms subcontract over 50 percent of the inputs and intermediary goods from small firms, thus reducing their scale and vulnerability. The organization of large firms and small firms is able to achieve economies with a relatively lower level of production.

The small firm plays a secondary role in technological change in Sylos Labini´s oligopoly vision. In the Schumpeterian vision, it plays a transitory role because of its importance in the initial stages of innovation. The small firm has proven its economic and technological power by its characteristic flexibility not only in periods of prosperity and relatively easy growth but also in crisis periods (Schmitz 1990:280).

A strategy of technological development for small companies is suggested in order to increase profitability. Pratten concludes that if small companies can be as profitable as large ones, then both types of companies can coexist (199 r: 3 I). As a consequence, small companies must coexist with big oligopoly companies, which have their own sources of technological and organizational knowledge. Many large companies are reorganizing to diminish their costs, bureaucratization, inflexibility and their waste of resources. Therefore, they are searching for new forms of collaboration with other large and small companies through alliances, joint ventures, and subcontracts. Some regions of Asia and Europe, by creating linkages between firms, government, and intermediary institutions, have subordinated the individual competitiveness of one firm and have invented the concept of systemic competitiveness (Messner 1996).

The concept of systemic competitiveness is especially relevant for countries like Mexico where 98 percent of the productive structure is made up of micro and small firms (between I and 100 workers). The statistics show that the number of small firms has decreased since structural reforms and macroeconomic stabilization began. It is suggested that such policies have not created a propitious environment for the development of micro and small firms, focusing only on the needs of large national or international corporations. In order to spread the benefits of economic restructuring among the smaller firms, policy makers should worry about creating the "right institutions," not simply about “getting the prices right” (Williamson 1993).

Specification of the Production Function and Parameters

Entrepreneurs organize their knowledge, training, and experience according to the profit maximization objective subject to their resource constraint. Firms try to choose the most efficient combination of the different human and physical factors involved in the production of goods, in order to accomplish the objective. The technical relationship between factors of production and output, as mentioned before, is the production function (Nicholson 1998:204). The production function is generalized as follows: Q = f (K, L, M.....). Output (Q) depends on combinations of capital (K), machinery and equipment, labor (L), number of workers or working hours, and materials (M). The notation (……) represents the other factors affecting production such as technology, training, education, learning, and entrepreneurial capacity.

The production process of a firm, which is represented by the production function, determines the cost structure and its responsiveness before production changes. The production function determines the ability to generate profits and to ensure the firm's expansion. An efficient productive process should ensure sufficient flow of resources to cover costs, investment requirements, and the risk taker's profits. Thus the firm expands and accomplishes its social objective of providing jobs.

The Cobb-Douglas (CD) and Constant Elasticity of Substitution (CES) production functions are suggested in order to analyze the production processes of the sample of first under study. These functions possess specific characteristics that facilitate analysis of the production structure.

Equation 1 shows the CD production function:

Q = AKB1LB2, (1)

where A is the efficiency parameter capturing the part of the output not attributed to K nor L, but to technical progress. Constants BI and B2 are the product elasticity of capital and labor. They measure the percentile change of output from a 1 percent change of capital and/or labor. The summation of B 1 and B2 represents the homogeneity degree of the production function, that is, the kind of returns that the production function exhibits. B 1 + B2 = 1, B1 + B2 > 1 or B1 + B2 < 1 represent constant returns to scale, increasing returns to scale, and decreasing returns to scale, respectively. They also represent the share of capital and labor in production. Therefore, B1/B2 represents the capital-labor ratio, the factorial intensity. Since the creators of the CD production function, Charles Cobb and Paul Douglas, found empirically that B1 + B2 approaches unity, it is regularly assumed that CD shows constant returns to scale (Berndt 1991: 451). By linearizing equation I through natural logarithms, as in equation 2, estimation of the CD function is possible by the use of the method of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS):

Ln Q = Ln A + B1 Ln K + B2 Ln L (2)

Arrow found that the CD production function is too restrictive since it assumes a unitary elasticity of substitution. He thought that the elasticity of substitution could take other values different from unity. As a consequence, Arrow proposes the Constant Elasticity of Substitution production function (CES), which relaxed the unitary elasticity of substitution assumption and allowed this parameter to take a different but constant value. It's shown in equation 3:

Q = γ [δK- ρ + (1 -δ) L- ρ]-ν/ ρ (3)

Parameter γ is the efficiency parameter, which is similar to parameter A of the CD function. Parameters δ and (1- δ) represent the distribution parameters, which define the proportion of capital and labor relative to output, respectively. The constant ρ represents the substitution parameter used to obtain the elasticity of substitution π = (1/ 1- ρ). Finally, constant v represents the homogeneity degree of the production function (Katz 1970:40). Thus, ν=1, ν>1, and ν<1 represent constant, increasing, and decreasing returns to scale, respectively.

The elasticity of substitution (π) measures the variation of the K/L ratio before variations of the marginal rate of technical substitution along the isoquant. The marginal rate of technical substitution is the ratio of the marginal product of capital and marginal product of labor (Nicholson 1998). It also shows the flexibility by which one factor is substituted for another in the production process (Teshome 1980:276). If it is assumed that labor wages should be equal to marginal productivity, then the marginal rate of technical substitution will become w/k, the ratio wages (w), and capital price (k). Therefore, this analytical parameter shows the substitution between capital and labor when the factor price ratio changes (Williams, 1974). If the value of n is high (greater than I), substitution of labor for capital is easy. If n is low (1 or lower), substitution between capital and labor is difficult.

Estimation of CES parameters is more complicated than that of the CD function. Greene (1998:344-346) suggests an indirect estimation method for the CES function. First we must take the natural logarithms of the CES production function as follows:

LnQ = Ln γ - ν/ρ Ln [δK- ρ + (1-δ)L- ρ] (4)

A Taylor series approximation around ρ=o applied to (4), results in:

Ln Q = Ln γ + νδ Ln K + ν(1-δ) Ln L + ρνδ (1-δ){-1/2 [Ln K -Ln L]2} (5)

Transforming (5) results in:

Ln Q= B1X1 +B2X2 +B3X3 +B4X4, (6)

where B1, B2, B3, and B4 are the parameters to estimate through the OLS method and

X1=1, X2-Ln K, X3=Ln L and X4=-1/2 [Ln K -Ln L)2.

Finally, the following transformations are used in order to obtain the proper parameters:

γ=eB1, δ=B2/(B2+B3) ν=B2+B3 ρ=B4(B2+B3)/(B2B3)

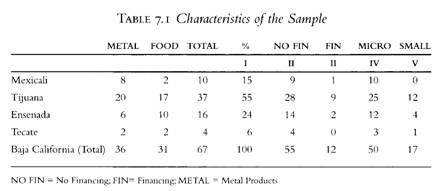

A survey was designed and applied to 67 MSF of the metal products and food manufacturing branches during the period from June to September in 1999 in the Baja California cities of Mexicali, Tijuana, Ensenada, and Tecate, in order to estimate their production functions. The number of firms in the sample was limited by the amount of financial resources and human capital dedicated to data collection. The distribution of surveyed firms is shown on Table 7. I. The survey includes diverse aspects of the firms' operations such as owner characteristics, human resources, production, costs, technology, and finances.

The production functions represented by equations (2) and (6) were applied to the cross section data available from the sample of firms shown on Table 7. I. As proxy variables of Q, K, and L, the models include the value-added output (VAij), the value of capital assets (VAFij), and the hours worked per person (HHAij) in the year i=1998 for each firm surveyed (j). VAij was the result of subtracting the operation costs from the production value. If we include the proxy variables, models (2) and (6) transform to:

Ln VAij = Ln A+B1 Ln VAFij+B2 Ln HHAij (2.a)

Ln VAij=Ln B1+B2 Ln VAFij+B3 Ln HHAij+B4 {-1/2 [Ln (VAFij/HHAij)]2} (6.a)

Estimation and Results of the CD and CES Production Functions

The expressions (2.a) and (6.a) were applied to the total sample of MSF (1), to the MSF that had no banking or government financing-that is, firms whose production processes were financed by the owner's resources (II)-and to the firms financed by banking or government loans (III). Additionally, models 2.a and 6.a were extended to micro (IV) and small firms (V) with 1 to 30 and 31 to 100 workers, respectively, in order to detect structural differences between the firms of different sizes under study. The sample structure is shown in Table 7.1.

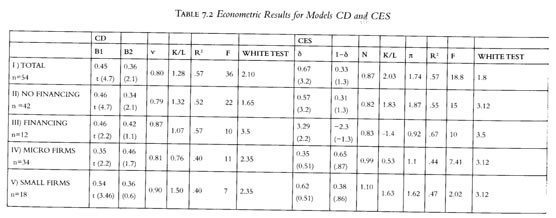

As mentioned above, transformations and computations were done with the results in order to obtain the factor shares, B1 and B2 for the CD function and δ and (1-δ) for the CES function, the intensity of factors (K/L), returns to scale (ν), and elasticity of substitution (π). The econometric results are presented in Table 7.2, the CD production function results indicate that the capital contribution (B1) in the value-added output is similar in cases I, II, III (0.45). Labor contribution measured by B2 is similar in cases I and II (0.36 and 0.34, respectively) but not in case III. The labor's share in value-added in case III is higher than in cases I and II (0-42). This result may suggest that the availability of financial resources in those firms is not used to purchase better capital since the production processes of firms with access to financing exhibit relatively less utilization of capital (K/L= 1.07).

The initial results derived from the CES production function indicate that the factor contributions in cases I and II are similar in terms of labor factor. Case I shows a higher contribution of capital in value added than case II (0.67 and 0.57 respectively). In case III, factorial contribution is not clear since the parameter has the wrong sign and differs from the result suggested by theory.

An important parameter defining the production processes of firms is the kind of returns that they exhibit. Table 7.2 shows that the CD production functions in cases I, II, and III exhibit decreasing returns to scale (0.80, 0.79, and 0.87 respectively). However, the group of firms with access to financing (III) exhibits higher returns to scale than the other two cases (I and II). According to CD, the group of firms with bank or government financing seems to present higher levels of efficiency than those without such financing. The CES production functions also show slightly higher values in terms of the returns of the firms receiving loans (0.83)) compared with those that do not (0.81). According to Berndt (1991), the CES production function provides a better estimation of the degree of homogeneity of the function than the CD function. The latter assumes regularly constant returns to scale. Thus we can conclude that the level of efficiency of the group of firms with access to financing and the group of firms with no access to financing is similar to the returns to scale provided by the CES function (0.83 and 0.81, respectively).

In order to define and differentiate their production processes, the same analysis was extended to both micro (IV) and small (V) firms. In addition the elasticity of substitution and the K/L ratio were estimated to detect social development potentialities derived from each group of firms. The results of the CD function indicate that micro firms (between 1 and 30 workers) exhibit decreasing returns to scale (ν = 0.81) and their production processes tend to be labor intensive (K/L= 0.76). Small firms (between 31 and 100 workers) also show decreasing returns to scale (ν=0.90) but relatively capital intensive (K/L= 1.50). Although in both cases for the CD function show decreasing returns to scale, small firms (V) exhibit higher efficiency levels as suggested by the function's degree of homogeneity. The CES results indicate that micro firms exhibit practically constant returns to scale (ν=0.99), whereas small firms show increasing returns to scale (ν= 1.10). These results confirm that the small firms have a higher degree of efficiency than micro firms do and are relatively capital intensive (K/L= I .6)). Micro firms use labor as the predominant factor (K/L=0.53). Thus the CD and CES functions show that small firms represent more efficient production processes than the micro firms do and are relatively more capital intensive. Finally, the elasticity of substitution provided by the CES function indicates that the substitution of labor for capital is easy in small firms (π=1.63) compared with micro firms (π=0.53). These results suggest that small firms are able to avoid paying wages above labor productivity by incorporating additional units of capital to increase labor productivity. The smaller firms have fewer possibilities to substitute labor for capital. Therefore they have to pay wages at market levels even when labor productivity is poor. They must either absorb the increase in costs derived from the gap between wage and productivity or simply leave the market. They avoid paying wages at market levels by incorporating informal workers such as relatives. This idea supports the fact that the smallest firms are more likely to be family run.

Concluding Remarks

With a focus on small firms, this study has described the industrial structures and evolution of Baja California and the role of small firms in its industrial configuration and has analyzed the theoretical elements that determine their behavior, advantages, characteristics, weaknesses, and potential for contributing to regional economic growth and development. Finally, we presented a regression analysis in order to test the following hypothesis: the extension of credit is associated with higher levels of efficiency, and small firms tend to exhibit less efficiency, higher labor intensity, and fewer possibilities of factor substitution as the literature suggests. Incorporating the empirical findings as guiding criteria in an institutional industrial policy for regional development is the most valuable contribution of this study.

The first objective was to determine whether credit availability from the banking system was associated with a higher level of efficiency. The results indicate that there is insufficient evidence to support an association between credit availability and efficiency and therefore that credit, at least for the Baja California firms in the sample, has not contributed to achieving higher efficiency. This result contradicts the idea that financing allows the purchase of technology that contributes to higher productivity. A key element supporting such a conclusion is that firms with access to credit showed a higher intensity of labor use than those with no access to credit. The firms in the sample must not be allocating financial resources according to efficiency maximization principles but rather different criteria. Financial resources may be allocated in debt restructuring, in working capital, or in just making ends meet while waiting for more prosperous times. There may be other explanatory factors as well. Efficiency of the group of firms having bank financing may be nullified by high financing costs derived from high interest rates. The financial costs may be placing a large load on the costs structure. This situation may be nullifying the positive impact on productivity derived from financing. Other elements of the firm's operation may be obstructing the productive use of financial resources, such as inefficient management systems, low levels of education and qualifications of managers, poor training, lack of new and more effective marketing and productive techniques, organizational inefficiencies, and so on.

The second aim of the research was to determine the production structure of micro and small firms in order to provide key elements leading to the selection of firms with the highest potential according to the criteria of social development. Thus, sectors with the highest potential are those having more labor intensity and low factor substitution possibilities. Table 7.2 shows that micro firms (between I and 30 workers) are the most labor intensive and have poor possibilities of factor substitution. The elasticity of substitution of micro firms has interesting possibilities for the regional development of Baja California. Since substitution of labor for capital is difficult and micro firms are labor intensive, increasing the number of micro firms, their level of production and their efficiency to a certain degree may contribute to the alleviation of poverty. These measures can contribute to eliminating unemployment and underground employment, improving the standard of living of a large part of the less favored social groups, and balancing the distribution of income. This can also raise the hopes of many people who cannot find jobs. Micro firms also exhibit less production efficiency when compared with small firms. Such results agree with the literature of small firm economics. Thus, the firms with the greatest potential to impact social development are the smallest firms. An industrial policy that supports the proliferation, growth, and efficiency of these firms should become the priority of economic development strategies. The improvement of this sector is closely related to the development of the less favored social groups and firms.

This study does not suggest subsidizing the less efficient companies but instead proposes mitigating the adverse effects of market liberalization and macroeconomic stabilization, which have marginalized small firms in favor of the development of the larger firms. Large firms have been able to obtain financing from the international financial markets and to enter the international markets of goods. Small firms, however, are forced to finance at high interest rates in the domestic financial markets. The small scale and lack of competitiveness of these firms do not allow them to enter the international markets of goods. If the small firms were a minority, we could allow the market to put the inefficient companies out of the market.

The official statistics, however, suggest that micro and small firms together represent 98 percent of total firms. Authorities should not leave it to the market to decide about this group of firms. Markets seem fair by giving the same incentives for all. The fact is that the economic agents are heterogeneous: some are influential and rich, but most are poor or insignificant compared with the size of the market. Thus, markets end up being unfair since they are made up of heterogeneous economic agents. The group with the greatest share of the market is the one that rules; therefore, allocation of resources through the market mechanism is biased toward the influential social groups that have market power.

Thus, an integral industrial policy is critical in order to balance the income distribution and to achieve the coexistence of all firms. Industrial policy refers to the collection of rules that define the industrial structure of a country (Mungaray 1997).The objective of industrial policy may be the reorganization of the conditions affecting positively or negatively the micro, small, and medium-sized firms. Industrial policy may also be defined as the collection of measures that facilitate the evolution of the industry toward the country's pattern of competitive advantage. Industrial policy instruments may include direct or indirect subsidies, special financial agreements, and protection against external competition, worker training programs, and the like (Weiss 1991).

How is industrial policy able to stimulate regional development? How can the findings of the research discussed here be useful in terms of regional industrial policies for development? Since regional development is a changing process that implies economic growth as well as an improved standard of living, industrial policy should consider the regional growth rate, provide for balanced income distribution, and better the living conditions of the less favored social groups, firms, and regions (Markusen 1995).

Industrial policy should be oriented toward the application of instruments according to the different needs of the sectors and regions, the efficient use of the production factors, the development of the potential of each region, and the redesign and adjustment of institutions toward the economic development objective (Ramamurthy 1998:23).

Industrial policy for micro firms in Baja California should not stimulate efficiency by increasing the scale or by utilizing more sophisticated capital. These strategies face significant obstacles since micro firms have small markets and scale and credit constraints. The industrial policy should create an institutional framework that emphasizes caring for the most abundant factor in the country: human capital. Institutions should be responsible for human capital education and training and should stimulate learning in order to take advantage of economies of learning and organization. Thus, human capital would generate more innovations for small firms, which would support productivity and competitiveness. In this sense, cooperation between institutions, such as universities and research institutes, and the productive sector can contribute to improving the efficiency of poorly performing firms (Manpower Services Commission 1988). Universities can provide training and technical assistance to small firms. Research institutes as well as universities can be the source of innovations, technologies, and production techniques that help improve the productivity of poor firms (Mungaray and Ocegueda 2000:1011).

Another important element that the authorities can provide in order to increase small firm efficiency is credit extension. Since credit extension does not assure efficiency by itself, it should take place once efficient use of resources is assured by entrepreneurial training, technical assistance, and proper allocation of resources. Credit extension at interest rates below the market rate has great potential to increase the productivity of small firms through the incorporation of physical capital. A small change in physical capital facilitated by an equitable credit extension policy for small firms can generate a large change in the productivity of these firms since they produce in a point of the isoquant where the labor factor is predominant and labor productivity is low (Fong 1990: 167-169).

Once advances in the efficiency of small firms are achieved, then other sophisticated and complex but appropriate forms of industrial organization of the Baja California industrial sector can take place in order to capitalize on the presence of large global firms. Thus, small regional or local firms can sign contracts with large global firms or can enter the international markets of goods.

The increased competitiveness of small firms is a necessary but not sufficient condition for contractual arrangements between large and small firms. The redesign of the institutions or the creation of the right institutions governing market exchanges and interfirm and other cooperative schemes are required. There is a need for regional institutions to protect contracts between firms and the credit extension arrangements between firms and the regional private or public banks. These institutions should create an environment conducive to cooperation between firms, federal, local, and regional governments, and other kinds of organizations such as universities and research institutes, and the community. The institutional change for small firm development should constitute an essential topic in further research on developing economies.

Authors' note: We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments from Franklin Ho, Maureen Burton, and Nestor Ruiz at Cal Poly Pomona and Enrique Dussel at UNAM, as well as the financial support provided by SIMAC 1998 # 980103004, UABC 1999 # 0663-312, and a scholarship from the International Center of California State University at Pomona.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ács, Zoltan J. 1992. "Small Business Economics: A Global Perspective." Challenge 35:6. (November/December), 38-44.

Ács, Zoltan J., and David B. Audretsch. 1990. "Small Firms in the 1990s: a European Challenge." In The Economics of Small Firms, edited by Zoltan Ács and David Audretsch, 1-22. Dordrecht/Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Archibugi, Daniele, Sergio Cessaratto, and Giorgio Sirilli. 1991. "Sources of Innovate Activities and Industrial Organization in Italy." Research Policy 20:4 (August), 299-313.

Aspe Armella, Pedro. 1993. Economic Transformation the Mexican Way. Lionel Robbins Lectures, no. 4. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Berger, S., Dertouzos, M. C, Lester, R. K., Solow, R. M. and Thurow, L. C 1989. "Toward New Industrial America." Scientific American 260:6 (June). 39-47.

Bernanke, Ben, and Gertler, Mark. 1987. "Banking and Macroeconomic Activity." In New Approaches to Monetary Economics: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium in Economic Theory and Econometrics, edited by William A. Barnett and Kenneth]. Singleton. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Berndt, Ernst R. 1991. The Practice of Econometrics: Classic and Contemporary. Reading, MA:

Addison-Wesley.

Blair, Roger D. and Kenny, Lawrence W 1984. Microeconomía con Aplicaciones a la Empresa.

México, D.F.: Libros McGraw-Hill de México.

Carlsson, Bo. 1999. "Small Business, Entrepreneurship, and Industrial Dynamics." In Are Small Firms Important? Their Role and Impact, edited by Zoltan J. Ács, 99-110. Boston:

Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Coase. R. H. 1937. "The Nature of the Firm." Economica (New series) 4: 16 (November), 386-405.

Cohn, Elchanan. 1992. "Returns to Scale and Economies of Scale Revisited." Journal of Economic Education 23:2 (Spring), 123-124.

Datta, S. K. and Nugent, J.B. 1989. "Transaction Cost Economics and Contractual Choice:

Theory and Evidence." In The New Institutional Economics and Development: Theory and Applications to Tunisia, edited by M. K. Nabli and J.B. Nugent. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Dosi, Giovanni. 1988. "Sources, Procedures, and Microeconomic Effects of Innovation."

Joumal of Economic Literature 26:3 (September), 1120-1171.

Economist. 1990. "Did America's Small Firms Ever Get Off the Launching Pad?" 315:7661 (June 30), 66. London.

--- 1993. "The Fall of Big Business." 32T708 (April 17), 13· London.

Fong, Chan Onn. 1990. "Small and Medium Industries in Malaysia: Economic Efficiency and Entrepreneurship." The Developing Economies 28: 2 (June), 152-179.

Gertler, Mark, and Simon Gilchrist. 1991.” Monetary Policy, Business Cycle and the Behavior of Small Manufacturing Small Firms." NBER Working Paper no. 3892. Cambridge, MA:

National Bureau of Economic Research.

Greene,Wiliiam H. 1997. Econometric Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Harper, Malcolm. 1984. Small Business in the Third 1M1rld: Guidelines for Practical Assistance.

NewYork: John Wiley.

Hayes, Robert H., and Gary P. Pisano. 1994. "Beyond World-class: the New Manufacturing Strategy." Harvard Business Review 72:1 (January/February),77-86.

Henderson, James Mitchell, and Quandt, Richard Emeric. 1980. Microeconomic Theory: A Mathematical Approach. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hulme, Dave. 2000. "Is Microdebt Good for Poor People) A Note on the Dark Side of Microfinance." Small Enterprises Development 1 I: 1 (March), 26-28. Essex, England.

Inaba, S. 1960. "Technical Innovations and the Functioning of Capitalism." Bulletin of University of Osaka Prefecture 4:19-28. Osaka, Japan.

Katz, Jorge M. 1970. Production Functions, Foreign Investment and Growth. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Krugman, Paul R. 1993. "Toward a Counter-counterrevolution in Development Theory." In Proceedings cifT7le World Bank Annual Conference on Development Economics 1992, edited by Lawrence H. Summers and Shekhar Shah. Washington: The World Bank.

Markusen, A. 1995."Interaction Between Regional and Industrial Policies: Evidence from Four Countries." In Proceedings of World Bank Annual Conference on Development Economics 1994, edited by Michael Bruno and Boris Plescovic. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Manpower Services Commission. 1988. Universities, Enterprise and Local Economic Development:

An Exploration, of Links. London: The Stationery Office Books.

Messner, Dirk. 1996. "La Competitividad Sistémica." Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios del Trabajo 3: 13-40.

Modigliani, F. 1958." New Developments on the Oligopoly Front."Journal of Political Economy 66 (June), 215-232.

Mungaray, Alejandro. 1992."Requirements for Skill, Training and Retraining in the Mexican Food and Drink Industry: The Perspective of the Nineties." Journal of International Food and Agribussiness Marketing 4:1, 71-93.

___. 1997. Organización Industrial de Redes de Subcontratación para Pequeñas Empresas en la Frontera Norte de México. México, D.F.: Nacional Financiera.

Mungaray, Alejandro, and Juan M. Ocegueda. 2000. "Community Social Service and Higher Education in Mexico." Statistical Abstract of Latin America 36:1011

Nabli, M. K. and Nugent, J.B. 1989. "The New Institutional Economics and Economic Development: 'Introduction' and 'Concluding Remarks.'" In The New Institutional Economics and Development: Theory and Applications to Tunisia, edited by M. K. Nabli and J.B. Nugent, 3-33 and 438-448. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Nicholson, Walter. 1998. Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Applications. McGraw Hill.

Nonaka, Ikujiro. 1991. "The Knowledge-Creating Company." Harvard Business Review 69:6 (November/December), 96-104

North, Douglass Cecil. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge, England/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Obrinsky, Mark. 1983. Profit Theory and Capitalism. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Press.

Ohmae, Kenichi. 1995. The End of the Nation State: The Rise of Regional Economics. New York:

Free Press.

Pappas, James L., and Brigham, Eugene F 1985. Fundamentos de Economía v Administración.

México: Interamericana.

Pratten, C.F 1991. The Competitiveness of Small Firms. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Pyke, Frank S., and Sengenberger, Werner. 1990. "Introduction." In Industrial Districts and Inter-Firm Co-operation in Italy, edited by Frank S. Pyke, Giacomo Becattini, and Werner Sengenberger. Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies.

Ramamurthy, Bhargavi. 1998. "Small Industries and Institutional Framework: A Transaction Cost Approach." In Institutional Adjustment for Economic Growth: Small Scale Industries and Economic Transition in Asia and Africa, edited by Per Ronnås, Örjan Sjöberg, and Maud Hemlin, 23-36. Aldershot, Hants, England / Brookfield, VT: Asligate.

Ruiz Duran, C. 1993."México: Crecimiento e Innovación en la Micro y Pequeñas Empresas."

Comercio Exterior 43(6): 525-529.

Ruiz Duran, Clemente, and Mitsuhiro Kagami. 1993. Potencial Tecnológico de la Micro y Pequeña Empresa en México. México, D.F.: Nacional Financiera.

Ruiz Duran, Clemente, and Carlos Zubirán-Schaedtler. 1991. Changes in the Industrial Structure and the Role if Small and Medium Industries in Developing Countries: The Case of Mexico. China, Japan: Institute of Developing Economies.

Schmitz, H. 1990. "Small Firms and Flexible Specialization in Developing Countries." Labor and Society 15:3,257-285.

Stewart, Frances and James, Jeffrey. 1982. The New Technology in Developing Countries. Boulder:

Westview Press.

Storper, Michael. 1985. "Oligopoly and the Product Cycle: Essentialism in Economic Geography." Economic Geography 61:3, 260--282.

Sylos Labini, Paolo. 1993. Nuevas Tecnologías y Desempleo, México: Fondo de Cultura Econ6rnica.

Sylos Labini, Paolo, and Enrique Irazoqui. 1966. Oligopolio y Progreso Técnico. Barcelona:

Oikos-tau.

Taylor, Lance. 1988. Varieties of Stabilization Experience: Towards Sensible Macroeconomics in the Third World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Teshome, MuIat. 1980. "Capital-Labor Substitution in the Ethiopian Manufacturing Industries." The Developing Economies 18:3 (September), 275-287.

Weiss, J. 1991. Industry in Developing Countries: Theory, Policy and Evidence. London:

Routledge.

Williams, Randolph L. 1974 "Capital-Labor Substitution in Jamaican Manufacturing," The Developing Economies 12:2 (June), 169-181

Williamson, Oliver E. 1990. "Introduction." In Industrial Organization, edited by O.E.

Williamson, ix-xxi. International Library of Critical Writings in Economics, vol. 9 Aldershot, Hants, England / Brookfield, VT: E. Elgar.

---. 1993. "The Transaction Cost Economics and The Organization Theory." Institutional and Corporate Change 2:107-156.

---. 1995. "The Institutions of Governance of Economic Development and Reform." In Proceedings of the World Bank Annual Conference on Development Economics (1994), edited by Michael Bruno and Boris Pleskovic, 171-197. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Yamamoto, H. 1959. "Small Firms and The Labor Problem in Japan." Bulletin of University of Osaka Prefecture 3:76-84. Osaka, Japan.

Copyright © 2006 - 2009 PROFMEX. All rights reserved |