Mexico and the World

Vol. 11, No 1 (Summer 2006)

http://profmex.org/mexicoandtheworld/volume11/1winter06/chapter5.html

CHAPTER FIVE

Export-Oriented Production

and the Agricultural Labor Market in

the Northwest Border Region of Mexico

Sonia Lugo Morones

THE AGRICULTURAL EXPORT labor market in the northwest border region of Mexico1 has organizational characteristics very similar to those of the states of California and Arizona. The similarity is due to the origins and history of the region and of the business enterprises under the regulatory system of the free zone, as well as the origin of investment and stock of personnel, infrastructure, and government services at various levels.

Since 1995 the behavior of the agricultural labor market has undergone structural changes that have a social and economic impact on its surroundings. What are the causes and effects of these changes? What happens to wages? What is the role of migration? What are the short- and medium-term expectations? These are the questions I will try to answer here. Their importance relies on the agricultural labor market's structural change, which has become inextricably mixed with change in the industrial and service labor markets.

The study begins with the export-oriented, fruit-and-vegetable agricultural market as a study framework and continues with an analysis of the agricultural export market. The main determinants of the structural changes that have occurred over the last few years are also discussed. The results of this study are based on the information supplied by official sources, especially the Program for Agricultural Day Laborers of the Secretaria Desarrollo Social (Secretariat of Social Development) (SEDESOL), as well as firsthand information from the 1,380 surveys from September 1999 to May 2000 taken in the states of Baja California (460), Baja California Sur (460), and San Luis Rio Colorado, Sonora (460).

Regional Agricultural Specialization and Globalization

In a world becoming more and more globalized and at the same time fragmented into great economic blocks, agricultural production-the foundation of the food supply and the input for the manufacture of many industrial products continues to play an important role. World agricultural trade is considered by some countries to be part of their food security, in the sense that income from foreign agricultural trade is used to buy food.2 Consequently, despite global tendencies toward a more open market, agriculture is moving in the opposite direction, with an open market existing only as a complement to global necessities. Even greater protective measures, such as the technical barriers regarding trade in agricultural products, are used to regulate the marketing of agricultural products.

Currently, one of the technical barriers to trade most discussed is the food safety program that US. President Bill Clinton presented in October 1997. This program invites fruit and vegetable growers who want to export to the US. to adopt "good farming practices," which include cleanliness and maintenance and inspection of all processes of production and distribution up to the time the fresh food reaches the consumer.3 The program addresses certification of soil, water, and seed; specialization of workers; and physical infrastructure necessary for the production, transportation, and consumption of the products. At present, these measures are not mandatory, but a vigorous publicity campaign warns people not to use products unless they know how they are produced and whether they are safe for consumption. Anyone who wants to remain in the international fresh food market must be willing to comply with the new international rules for food safety.

In the world of agricultural trade, products such as fruits and vegetables play an important role. China and the U.S. are the main producers, Germany and the U.S. are the major importers, and the main exporter is Spain. Two percent of the world agricultural market belongs to Mexico, which specializes mostly in fresh vegetables and exports, with 84 percent of its production going to the US. market. Imports from Mexico represent 68 percent of US. imports, followed by Canada with IS percent. The main products imported by the U.S. are tomatoes (3S percent), bell peppers (17 percent), onions (7 percent), cucumbers (7 percent), squash (S percent), potatoes (S percent), and asparagus (4 percent).

The U.S. showed a negative tendency in its balance of agricultural trade from 1992 to 1998, with a deficit of approximately one billion dollars in fruits and fresh vegetables, owing to an increase in the importation of vegetables, with a significant rate of growth since then. Exportation of fruits (especially apples, pears, peaches, grapes, nectarines, along with potatoes and lettuce) to other countries compensates for the increase in vegetable imports. In Mexico the important vegetable producers are Sinaloa, Baja California, Sonora, and Baja California Sur. The latter two have increased their production since 1997, through companies that have migrated from Baja California or Sinaloa. The greatest productive strength is found in the first two, with Baja California producing approximately 30 percent and Sinaloa 60 percent; among the four they form an annual production cycle. Baja California's production season is basically summer and Sinaloa's is winter. Of the large variety of vegetables, the most important are tomatoes, cucumbers, bell peppers, and onions.

Most of the vegetables are produced in the northwest of the country where the soil and weather favor crop growth, especially in the fall/winter cycle (Munoz Rodriguez et al. 1991), when conditions in the US. are not conducive to production. Thus, they constitute an offering that complements production in the US.: Sinaloa with Florida in the fall/winter cycle, and Baja California with California in the spring/summer cycle (Schwentesius 1997).

Mexico's northwest frontier region shares a common social and economic history with the US. border states of California and Arizona, giving rise to an important cultural and economic interaction. In this context, leading international distributors of fruits and vegetables, in association with Mexican agricultural companies, tend to create local advantages in competition, especially regarding costs. The distributors have the capital and the infrastructure to promote the product in the international market. Although joint ventures predominate, some Mexican companies own their own marketing firms in the U.S. and export under their own brand name. As a result, vegetable production is an integrated effort that makes for a transborder agricultural zone. Ranfla (1988) has found that "vegetable production in the Mexicali Valley is not competing with that of the Imperial Valley in the US. market; instead, the two work together nicely, thanks to the distribution circuits operating in the two valleys." Therefore, by combining the production factors of both sides of the frontier in this zone, companies reach a "high regional productivity, due to the technological level" (Calleros 1990), creating competitive advantages. The same thing happens in the valleys south of Ensenada and north of Los Angeles.

The agricultural export sector maintains a surplus in Baja California's balance of trade report, in which, apart from the maquiladoras, chapter 7 (vegetables) is the most important (Secretaria de Desarrollo Económico 1998) in export value, followed by fruits and fish. One of the strategic clusters considered by the state government is food products, along with electronics and wood products.

Productive Specialization and Regionalization

As an example of the production of fresh food products, especially fruits and vegetables, let us consider the agricultural regionalization of the rural development districts: 001 Ensenada, composed of the municipalities of Ensenada, Playas de Rosarito, Tecate, and Tijuana, with 258,802.5 acres; 002 Rio Colorado, which includes the municipalities of Mexicali and San Luis Rio Colorado, Sonora, with 460,707.5 acres. The main farm production of vegetables for export is in the spring/summer cycle in District 001 and the fall/winter in 002. These districts are known as the Coastal Zone and Mexicali Valley, respectively. Baja California Sur is considered a separate region because its production represents 20 percent of the Coastal Zone's total yield, and 75 percent of that of the Vizcaino Valley, south of Guerrero Negro.4

THE MEXICALI VALLEY AND THE CULTIVATION OF GREEN ONIONS

The history of the Mexicali Valley is linked with that of the Imperial Valley, since the latter gave birth to the former.5 At the beginning of the twentieth century the irrigation society Terrenos de Baja California (Baja California Irrigation Society), a branch of the Mexican Land and Colonization company, built a system of canals there (Stamatis 1987). Because of the physical features of the terrain, the Mexican side was built first, by a predominantly Asian work force, both as construction and as agricultural labor. In the 1930s, President Lázaro Cárdenas, in an event known as the "El Asalto a las Tierras [Assault on the Lands]," seized the lands and distributed them among Mexicans repatriated by the U.S.

The pattern of cultivation evolved from cotton mono culture to the production of forage and vegetables, the latter experiencing significant growth after the international drop in the price of natural fibers in the 1970s. In 1965 vegetables represented 0.73 percent (Fuentes 1992) of the Mexicali Valley's total agricultural production value. Thirty years later, in 1995, the share of vegetables had increased to 38 percent (SARH 1995). Cotton production dropped from 70 percent of farm production value in 1965 to 17 percent in 1995. This change in crop distribution is directly linked to the role of foreign investment in financing sector productivity.

The main export vegetable of the Mexicali Valley is green onions, followed by asparagus, leeks, and lettuce. The main producers in the Americas are the U.S., Canada, and Mexico; in Europe, the leading producers are France, Italy, and Holland. The most notable characteristic of this market is that the decisions or production plans must be made with the expectation that the prices prevailing at the beginning, when the fields are being prepared for planting, will remain stable until the harvest. While purchasers are able to adapt to changes in prices, the agriculture company responds with a certain slowness, since most crops take time to get ready for market. Green onions are a labor-intensive crop and have an inelastic offering (Acosta, Lugo, and Avendano 2001). They are grown mainly in the fall/winter period, but their cultivation has been increasing in spring/summer.6 The production period extends from October to May, using up-to-date technology, local labor, and imported investments. The investment structure is 62.5 percent national, 25 percent foreign, and 12.5 percent mixed (Lugo 1997). It is a representative product of the district and has dominated the market, displacing California growers-which has made the growers work in alliance with foreign marketing companies, although 10 percent of the growers have their own marketing companies.

The most important competition problem is between the local growers, not with those outside the country. Although individually they are too small to influence the price, together they have enough power to fix it. This is not possible, however, because of the tension between regional companies with national and transnational capital. The market information for 1993 to 2000 indicates that in order to maintain a price of $6 per box,7 it is necessary to limit the agricultural offering8 to 400,0009 boxes per week. Increasing the offering to 500,000 boxes per week entails a price drop to $5.50, and exporting 600,000 boxes per week means dropping the price to $ 3.50. Once the market is saturated, it no longer reacts and maintains an inelastic behavior with respect to the price. In contrast, if the offering is less than 400,000 boxes per week, the price goes up, so that a bad harvest season means nice profits for the growers (Lugo and Avendaño 2000).This example illustrates how, through high-technology and the specialization of the labor force, the production in the Mexicali Valley dominates the international green onion market from October to May.

THE COASTAL ZONE AND THE CULTIVATION OF TOMATOES

The history of the Valley of San Quintín dates to the end of the ninetenth century when wheat was the area's major crop. The English owned and operated a mill to produce flour for the European market but abandoned the project during the Mexican revolution. After the revolution, some families began to grow vegetables for export, and in the 1970s there came to be an infrastructure for the cultivation of tomatoes for export, employing up-to-date technology and migrant labor. The tomato is considered the queen of vegetables, although it is marketed when ripe, it has a negative growth rate of per-capita consumption, its price has had a tendency to drop over the last three years, and it has been affected by disloyal trade practices. Nevertheless, tomato production is increasing, and productivity and yield per acre have increased. The minimum production cost in Sinaloa is $5.50 per box, and in Baja California $4.30. For this reason, U.S. growers have set a minimum price for the importation of Mexican tomatoes: a: winter rate of$5.50 and a summer rate of$4.30.As a result, tomato growing goes on all year in greenhouses, with production taking place during the period from October to December in the state of Baja California Sur where it is cheaper. Tomatoes are an extremely competitive product By employing high-tech production methods, growers can benefit from their comparative advantages in labor costs. They also compete through specialization and by continually seeking out new international markets.

THE VALLEY OF VIZCAINO AND ITS EXPORT COMPLEMENTATION

In the state of Baja California Sur farm production for export is located in three extended regions. The Santo Domingo Valley,10 to the north of Ciudad Constituci6n, produces grains, chickpeas (garbanzos), cotton, asparagus, and melons; the La Paz area11 and the Valley of Vizcaino12 produce export vegetables such as tomatoes, bell peppers, zucchini, and cucumbers grown on large ranches with investment by growers from Sinaloa and Baja California, respectively. The big export companies in the region of La Paz and Vizcaino have been prominent in these valleys for ten years, and their activity has increased steadily since 1997· The predominantly migrant labor force works in the greenhouses and fields under conditions reminiscent of those in San Quintín ten years ago.

The Formation and Structure of the Labor Market

The northwest border region, which includes Baja California and part of Sonora and Baja California Sur in Mexico, is socially and financially linked with the Southern California/Arizona region of the U.S. Population centers like the Imperial Valley and the Bahia de San Quintín have been devoted mainly to agricultural production; Tijuana to cattle raising, agriculture, and commerce; Ensenada to mining, agriculture, and fishing; and Baja California Sur to mining and agriculture.

In the 1980s, the production pattern for traditional crops like grains and forage was altered to emphasize export products with higher prices in the international market, but that required an intensive labor force. For the Mexicali Valley, this meant specialization of its local workers in bunching green onions and picking cotton, for which a migrant labor force was occasionally used. On the other hand, in the San Quintín Valley the labor force was scarce, which made it suitable for the migration of agricultural workers basically from Oaxaca, Guerrero, Sinaloa, and Sonora to work in the valley's large agricultural companies.

Since then, and up to the beginning of the 1990S, there was an established and steady pattern of agricultural migration and of the characteristics of the laborers in the San Quintín Valley. Those who worked in the open fields were of indigenous origin; entire families migrated and participated. Those who worked in the packing plants, drove tractors, and carried on more highly specialized activities came mostly from Sinaloa or Sonora. The hiring of the majority of the workers took place in their places of origin, from which they followed a route to the valleys of Sinaloa, Sonora, and Baja California. Little by little the workers settled in these areas, basically because of the specialization they had developed. The companies eventually became obliged to cultivate winter products such as strawberries and zucchini to provide year-round employment to these workers, since it was difficult to find others who could do their important jobs. The companies even provided housing, transportation, and other benefits. The percentage of local laborers in 1990 was not greater than 12 percent.13

By contrast, in the Mexicali Valley, the labor force was mainly composed of local residents who specialized in bunching green onions, a winter product grown predominantly in this valley.14 However, every devaluation of the peso with respect to the dollar resulted in an increased migration flow of the best workers to the fields of California and Arizona. This northward migration gave rise to the need for the training of new workers and to a scarcity of agricultural engineers, who are always the first to leave. Five percent of the migrant workers in the 1990s were agricultural engineers.

With the change from free trade zone to a zone of increased regulation pertaining to trade and industry, Mexicali began an energetic promotional campaign resulting in the establishment of large transnational companies and the displacement of the agricultural companies to the maquiladoras still in the same valley. South of Ensenada and in Baja California Sur, more export agricultural companies were established. As a result, the production of tomatoes increased by 150 percent from 1990 to 1997, due to an increase in technological investments and the opening of new lands for crops and other vegetables.

According to data from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Information Technology) (INEGI), the unemployment rate in Baja California is barely 1.9 percent. This low figure translates into a scarcity in the labor force, even though migration increases by 4.9 percent annually. This phenomenon is especially evident in the Mexicali Valley because of the growing presence of transnational companies and the displacement of the agricultural work force to the industrial sector. The impact on the increase in agricultural salaries has been notable. Wages increased from $5.50 to an average Of$I1.87 a day between 1997 and 2000, for approximately 70 percent of the workers, according to data from a survey taken in this valley from April to May 2000.

Because labor has been scarce in the Coastal Zone since the I950S when the first crops were planted, migrant workers were introduced. As more and more of these workers stayed, they created networks of employment agencies organized specifically to bring workers into the region. Government policies oriented toward an investment in services for migrant workers, facilities for housing and education, as well as the increase in vegetable production during the winter cycle brought about a shift in the percentage of residents and migrants. In 1990 migrants represented 12 percent of the population of the area, and in 1996, 28 percent. By 1999 to 2000, the migrant population (62 percent) had converted the previously rural areas into well-defined urban-rural zones.

Since 1997 the price of tomatoes has tended to decrease, and the regional growers have had to diversify production. Such is not the case for the transnational companies, whose costs are lower, nor for the Sinaloan companies, which were established only a few years ago and only produce during the summer months. The region's traditional companies maintain the workers who have stayed. Some of these companies are increasing their autumn/winter production in Baja California Sur with tomatoes and melons. The migration of agricultural companies carries with it the migration of workers, which in turn alters the traditional migratory route and increases the migratory phenomenon directed toward the south of the peninsula. In regards to salaries, they have remained at $6.50 a day, in large part because of the stability of the farm workers in the zone and the fact that the companies reduced their production by 50 percent as a result of water scarcity and labor problems.

There has been a migratory movement of laborers because of a change in the traditional production zones and a change in the conditions faced by the laborers: from a small settlement with rural characteristics to a rural-urban one. People who stay on as residents in the zone no longer want to work in the fields and are migrating to Ensenada. The city has encountered problems in generating sufficient employment opportunities, in spite of the fact that four transnational companies are located there and that the area is a seaport with maritime activities.

Characteristics of Agricultural Laborers

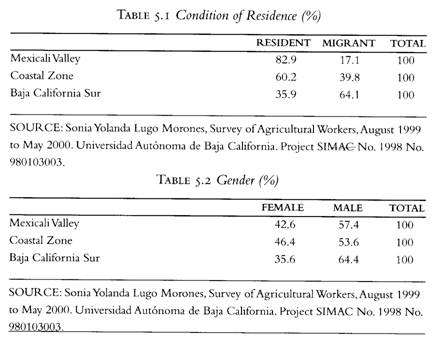

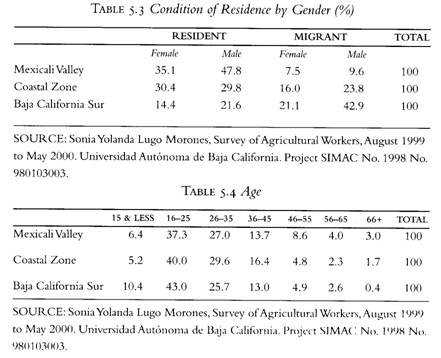

Analysis of the number of residents and migrants in the three study zones shows that the labor force is mostly local-although in Baja California Sur, it is migrant (Table 5.1) and predominantly male (Table 5.2). It is important to remember that until 1997 most of the workers in the Coastal Zone were migrants, which meant a change in residence for the farm workers before that time. Relating the variable of gender with that of residence (Table 5.3), there are more women residents in the Coastal Zone than men, possibly a sign of the evolution of the population from migrant workers to residents. Traditionally it is women who, when they stay, form families and increase the population of the communities. In fact, in those regions where only men emigrate, there is no community development until women set it off.

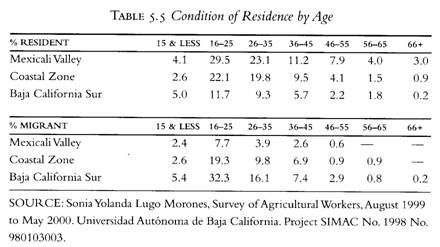

The data show a young population between 16 and 35 years of age, while more than 75 percent of the workers in the three zones range from 16 to 45 years of age (Table 5-4). Relating age with condition of residence (Table 5.5), one observes similar patterns in the three study zones, since the majority of the population is young and the largest percentage is between 16 and 25 years old, followed by those 26 to 35. If there is a significant difference regarding the work age, it is in the under- 15 age group, which accounts for a larger percentage in Baja California Sur. Because the percentage of residents is higher in the Mexicali Valley and in Baja California Sur, one may conclude that this is related to social and cultural characteristics of the workers. In the valleys of the Coastal Zone, a substantial investment in education and special programs is producing results. Surveys show that this zone has the lowest number of young workers, as well as a healthy equilibrium between migrants and residents.

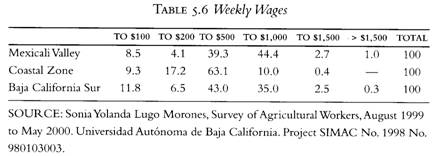

With respect to the salaries (Table 5.6), both in the Mexicali Valley zone and in Baja California Sur, the average minimum daily wage is higher for more than 70 percent of the agricultural workers. The lower average daily wage prevailing in the Coastal Zone may be explained by the increase in the number of residents during the last three years.

In the Mexicali Valley, for 87.3 percent of the workers, the average daily wage is $107.14 (pesos) or its equivalent in dollars ($11.87).15 This is much higher than the earnings of employees in the maquiladora industry, which vary from 64 pesos to 71 pesos a day.

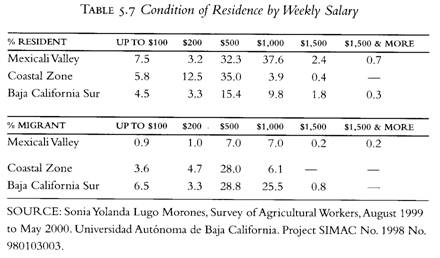

Regarding salaries by condition of residence (Table 5.7), 84.85 percent of the migrants earn $11.87 a day, slightly more than residents, which means that migrant status does not mean lower wages. On the contrary, migrants are paid more. In the Coastal Zone, the weekly salaries are $IOO (9.3 percent), up to $200 (17.2 percent), up to $5000 (63.1 percent), up to $1000 (10 percent), and up to $1,500 (0-4 percent). This means that 80 percent have an average income of$6.50 a day. In Baja California Sur, wages average $10.50 a day, which is much higher than in the Coastal Zone but lower than in the Mexicali Valley. In spite of cultural similarities, wages differ greatly due to the scarcity of farm workers and the fact that the migratory route to the Coastal Zone is new. It is important to make clear that the work in this zone is seasonal, from October to December, complementing the agricultural cycle of Sinaloa and Baja California.

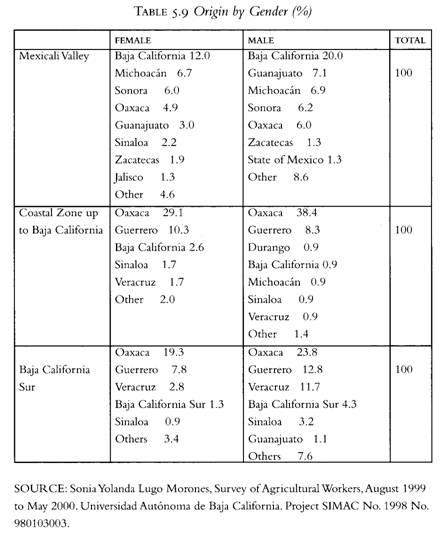

The analysis of the origin of the labor force (Table 5.8) shows that workers in the Mexicali Valley come from the states of Baja California, Michoacán, Sonora, Oaxaca, and Guanajuato. The analysis by condition of residence, however, shows that the migrants are from Baja California and Oaxaca and that the residents are from Baja California and Michoacán. This is explained by immigration within the state-from the Coastal Zone to the Mexicali Valley and vice versa.

As to origin by gender (Table 5.9), the women are from Baja California and Michoacán and the men predominantly from Baja California and Guanajuato.

Analysis of the Coastal Zone shows that the workers are mostly from Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Baja California. The analysis by condition of residence shows the same relationship for migrants as for residents, but when the variable of gender is added, the result is similar for both men and women, except that in the case of men it also includes individuals from the state of Durango.

In Baja California Sur, the agricultural workers come mostly from Oaxaca, Guerrero, Veracruz, and Baja California Sur. The state is similar to the Coastal Zone in the first two aspects, but a substantial number of workers come from Veracruz. Analysis by condition of residence shows that those from Oaxaca and Baja California Sur are residents and those from Oaxaca and Guerrero are migrants. A study by gender gives the same result for men and women, and the results for the states are the same, which is also true for the Coastal Zone.

With respect to the level of education, 15.1 percent of the workers in the Mexicali Valley have no schooling; 34.0 percent have some elementary school education; and 24.4 percent have finished elementary school, which means that 73.5 percent of the population has finished elementary school. Only 20.4 percent have some junior high school education; 5.1 percent have some high school education; and 1.1 percent have some other schooling.

If the education variable is analyzed by condition of residence, the number of agricultural workers who have not completed elementary school is greater among residents (35.1 percent) than among migrants (30.1 percent). More migrants have finished junior high school (11.5 percent) than residents (8 percent). By gender, there is a higher number of men with no schooling and a higher number of women who have finished junior high school, indicating a need for more elementary educational programs for boys and for junior high school programs for girls.

In the Coastal Zone 30.1 percent have no schooling; 43.0 percent have not finished elementary school and only 16.9 percent have, which means that 89.9 percent have completed at least elementary school.

Analysis by condition of residence shows that 34-4 percent of the residents and 24.9 percent of the migrants have no schooling. By gender, the proportion is higher among women. The condition of Baja California Sur is similar to that of the Coastal Zone: of the agricultural workers, 29.5 percent have no schooling, 41.1 percent did not finish elementary school, and 16.5 percent are elementary school graduates, these three groups accounting for 87.1 percent of the total. By condition of residence, 27.5 percent of migrants and 34 percent of residents are unschooled. By gender, 25.8 percent is the figure for men, and 34.6 percent for women. In both cases, this is a sign of the need to intensify educational efforts directed toward residents, especially women.

The major activity carried out in the Mexicali Valley is the bunching of green onions (55.2 percent). Packaging accounts for 17 percent. In this case, the workers decide where they want to work, depending on the season. This means that 43·6 percent of the workers have less than a year of continuous employment by the same company, although they have been employed by that company as seasonal labor in every year's harvest. Analysis of their living conditions indicates that 69.9 percent own their homes, while 13.9 percent live in loaned houses, and 10·5 percent pay rent. Also, 15 percent have lived at their present residence for less than a year, 18.4 percent have lived at the same place for from two to five years, and 16.5 percent for from five to ten years.

In the Coastal Zone the main activity is the picking of tomatoes (54.8 percent). Packing accounts for 10.0 percent. The workers make a decision about their place of employment, depending on the season, which means that 20.86 percent of the workers have less than a year of continuous employment by the same company. However, they have worked for that company as seasonal workers in every year's harvest. A study of their living conditions indicates that 43·9 percent of the population lives in camps or blocks of flats, 11.3 percent live in open, arbor-like camps, 31.2 percent own their own homes, and only 9.2 percent rent apartments. Of the total, 17.6 percent have lived at their present place of residence for less than a year, 14.5 percent have lived at the same place for 2 to 5 years, and 9 percent, for 5 to 10 years.

In Baja California Sur, the main activity is harvesting (54 percent). The most important crops are tomatoes (42.1 percent) and strawberries (33 percent), followed by melons (8-4 percent) and green peppers (6.5 percent). Other activities are packing and agriculture. The characteristics of this region are different because the workers are in camps distant from the urban zones and are hired from their place of origin for a period of six to eight months.16

From an historical perspective on the labor market's formation, its present conditions and its relationship to changes in productive specialization, we can define a series of stages in the development of the agricultural labor force.

BIRTH

1. Agricultural companies start their production or expand their production level and demand workers who cannot be found in the zone.

2. Salaries are high in times of great labor demand, including those for nonspecialized workers.

3. Agricultural workers have little knowledge of the area and the migrants are mostly men.

CONSOLIDATION

1. Agricultural companies greatly increase their production.

2. Migration to production zones is heavy, which satisfies the labor needs of the agricultural companies.

3. Migrants become residents of the zones and have greater access to education and other services.

4. Agricultural laborers know the migratory route perfectly.

5. Whole families migrate, including single women.

MATURITY

I. Laborers become residents of the area.

2. Area becomes urban-rural zone.

3. Migration continues, but less intensely, and low salaries are maintained.

4. Social problems arise because of growth in the demand for public services.

5. Women play an important role as residents in the zone.

DECLINE

1. Resident workers no longer want to work in the fields and start to look for work in other sectors, thus increasing the demand for workers.

2. Traditional agricultural production zones are fully mature and are beginning to experience scarcity of natural resources.

3. Other types of companies are established.

4. Companies begin to emigrate to other productive zones or to other countries.

5. Migration diminishes.

6. Salaries increase.

7. Migratory routes of the agricultural workers change.

8. The region changes the pattern of crops.

9. Scarcity of natural resources. ro. A new cycle begins.

From this perspective, the Mexicali Valley, which began with the establishment of foreign companies and an Asian labor force, finds itself once more in the stage of maturity and decline. It peaked with cotton production around the mid1950S but declined when there was a change in the crop pattern. The valley entered a new stage, beginning with vegetables, which ultimately experienced stages of maturity and decline. Companies were confronted with the problem of high salaries and migrated to the Coastal Zone. The valley is about sixty-six years old. The first cycle tends to be the longest. The second cycle began in the I970s.

In the Coastal Zone, the San Quintín Valley is in a stage of maturity, accompanied by a change in the structure of residents and social problems. It shows characteristics of decline because of the scarcity of natural resources and migration, which has brought about changes in the crop pattern. The San Quintín Valley is about forty-five years old. In the case of Baja California Sur, about ten years old, we are able to observe a growth pattern.

If these trends prevail over the next few years, it may be possible to find a modern field for agricultural companies in Baja California, with specialized workers having certification in "good agricultural practices," and in Baja California Sur, similar conditions to those found in Baja California today.

Conclusions and Perspectives

There is a structural change in the agricultural labor force associated with place of residence, educational level, salaries, and activities developed. This change is manifest in different ways in the Mexicali Valley and in the Coastal Zone. In both regions, however, the main characteristic is the production of export vegetables, which requires an intensive use of the labor force and which is complementary to the production of Southern California with direct, heavy, foreign investment. The three agricultural zones are different, but complementary, with defined labor force characteristics that force them to alter their activities and to redefine their situation in order to remain competitive in the international market.

One important conclusion is that, contrary to what one might think, in the cities the income of agricultural workers is greater than the income of maquiladora workers, with the exception of the Coastal Zone, where salaries are similar. This is explained by the migration of laborers and the change in residence structure, especially among women in areas where, after having become established in the zone, demand year-round employment and exert pressure on the price paid for their work. This is the case in the San Quintín Valley, where the federal and state governments have invested heavily in education and housing in an effort to improve conditions for the agricultural workers, especially the youngest. Data indicate that of the three regions, the San Quintín Valley is the one with the lowest number of workers under the age of fifteen, while Baja California Sur has the highest percentage of underage workers in the field. Baja California Sur is included because the migration of companies and workers gives it characteristics similar to those of the Coastal Zone at the beginning of the 1990s. Not considered is the Santo Domingo Valley, which resembles the Mexicali Valley.

The behavior of the agricultural labor market is one of perfect competition, with the labor market almost at full employment and scarce labor force. The workers have total freedom to move from one company to another, just as the companies have freedom of production. The international market, with its international prices, promotes this condition. If the international price of the product goes down, the grower limits production, stops hiring, and the workers go to other companies. The labor market behaves in this way because of the availability of jobs in the cities, which have little unemployment but where salaries do not increase, mainly because of the large migratory flow of workers.

Of the three study zones, where the migratory flow is more difficult, salaries are higher; where it is well defined and the workers know the region well, salaries are lower. There are other aspects of the labor market that have not been analyzed here, such as that of the agencies that hire the workers in their place of origin and bring them to the companies and the impact of the amount of funds the workers send back to their home regions.

The short-term outlook for the agricultural labor market in crops grown for export is one with a scarce labor force. Although in the Coastal Zone the resident population has grown, these people are in the stage of acquiring homes, completing their education, and trying to raise their standard of living. The search for work in other productive areas is just beginning to surface. This represents a problem for the municipality of Ensenada, which is neither economically nor socially prepared to take in this work force. Wages are relatively low, since although there is a constant demand for workers, migration tends to inhibit wage increases because it causes employment rates to remain high.

Over the medium term, changes may be observed as patterns of cultivation change from labor-intensive vegetables to capital-intensive vegetables; the market will be largely diversified and the labor force will be largely specialized. There will be cultivation of capital-intensive crops, whose production is beginning to cease in Southern California, and these will comply with all the mandatory security regulations for food products and meet the requirements for international certification. It is foreseeable that the new transnational companies may be Mexican-American companies converted into transnational ones, unified through co-investments with local producers who at the moment export under their own brand names and have marketers in the U.S. Also foreseeable is an increase in the migration of companies from the north to the south of the Baja California peninsula, with greater specialization among those that remain in the state of Baja California. This shift will, in turn, redefine the migratory route and the qualifications of agricultural labor, and salaries will tend to increase.

Author's note: This work is part of the research project The Agricultural Labor Market in the Northwest Border Region of Mexico, which was supported by The Cortez Sea System of Research (SIMAC) 980103004 and by the Regional Agricultural Union of Vegetable Growers of the Mexicali Valley.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Acosta, A., S. Lugo, and B. Avendaño. 2001. "El mercado de hortalizas del Valle de Mexicali." Comercio Exterior 51:3 (March), 303-307.

Calleros, J. 1990. Origen y desarrollo de dos areas de riego. Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

Muñoz Rodríguez, Manrrubio, Manuel Ángel Gómez Cruz, V. Horacio Santoyo Cortés and Víctor Sánchez Peña, eds. 1991. La agroindustria y la organización de productores en México. México: Centro de Investigaciones Económicas, Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y Agricultura Mundial-PIIAI, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo.

Fuentes, C. 1992. "Análisis de la evolución del patrón de cultivos y su efecto en la reorganización de la producción agrícola en el Valle de Mexicali (1965-1985)." Frontera Norte 4(7):179-202.

Lugo, Sonia. 1997. "Economía agrícola transfronteriza en el noroeste de México: Producción agrícola transfronteriza en el noroeste de México. El caso de Baja California." In México y Estados Unidos, EI reto de la interdependencia económica. Hermosillo, México: El Colegio de Sonora y Colegio de Economistas de Sonora.

Lugo, Sonia and Belem Avendaño. 2000. "Efectos regionales de la Globalización, el caso del cebollín en Baja California." Paper presented at Globalización y problemas del Desarrollo, Ciudad de la Habana, Cuba, January.

Lugo, Sonia, Oscar Castillo, and Patricia Melín. 2000. "Pronósticos de precios de hortalizas de exportación de Baja California." Paper presented at a meeting with the Secretaria de Desarrollo Económico del Estado de Baja California, November.

Mendenhall, William and James E. Reinmuth. 1993. Estadística para Administración y Economía. México: Iberoarnerica.

Ranfla, A. 1988. La polarización y subregionalización de la producción agrícola y el comercio en la frontera norte. Cuadernos de Ciencias Sociales, series 3, no. 4. Mexicali: Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales.

Schwentesius, C. 1997· "Competitividad de las hortalizas mexicanas en el mercado estadounidense." Comercio Exterior 47:12, 963--974.

Secretaria de Agricultura y Recurso Hidráulicas, Delegación Estatal en Baja California, Subdelegación de Agricultura, Jefatura de Fomento Agrícola. 1995. Evaluación de la producción de hortalizas durante el periodo de 1995. Mexicali: SARH.

Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico, 1998. Balanza Comercial del Estado de Baja California. Estadísticas Básicas. Mexicali, México: SEDECO.

Stamatis, M. 1987. "El Valle de Mexicali: Agricultura e inversión extranjera." Estudios Fronterizos 5:12-13.

Velásquez, Catalina. 2000. Migración china en Baja California. Mexicali: Universidad Autónoma de Baja California.

1. This market refers to the fruits and fresh vegetables or nontraditional products in the state of Baja California, Baja California Sur, and Sonora (San Luis Rio Colorado.)

2. For less-developed countries, such as the majority of the Central American and Caribbean nations, 80 percent of their exports arc agricultural products.

3. Known as the National Food Safety Initiative, it hopes to ensure that food products are clean and harmless and that permitted microbial content is limited to a minimum.

4. The Coastal Zone is composed of the valleys of San Quintin, Maneadero, Erendira, and Punta Colonet to the south of Ensenada and the valleys of Ojos Negros and La Trinidad to the east.

5. The Imperial Valley is located in Calexico, California, across the international border from the Mexicali Valley. Some writers use the term to include the regions on both sides of the border, in Baja California and Sonora as well as in California and Arizona.

6. The cultivation of green onions is increasing in the Coastal Zone, especially in the valleys of Ojos Negros, La Trinidad, and Maneadero-causing displacement of the specialized farm labor force tied to green onions in the summer season and giving these laborers year-round employment.

7. Prices are in U.S. dollars.

8. The agricultural offering is considered equal to the green onions exported to the U.S., not counting exports to Europe and Asia.

9. With the understanding that 100 percent of the agricultural offering of green onions is exported. What makes the difference between production and agricultural offering is the marketing process and the management of losses, which means that not all the onions produced are offered.

10. This valley has characteristics similar to those of Mexicali Valley, in the use of local labor, land tenancy, and the growing of such grains as wheat and corn, along with potatoes, for national consumption. For export, it produces chickpeas, asparagus, and other minor vegetables. The land tenancy is part of the ejidatario system, and there are no transnational companies. An ejido is a rural property of collective or communal use. The government would expropriate land and assign it to a group of people to form an ejido, which would then produce agricultural products for themselves and for trade.

11. In this zone only the La Campaña company is the property of Baja California growers. The rest belongs to growers from Sinaloa.

12. In this zone the growers are from the Coastal Zone of Baja California, which complements its production cycle. Workers are brought from that area to finish the harvest in Baja California.

13. Data provided by the President of the Local Farm Union of Vegetable Growers of the San Quintín Valley, in April. 1990, Engineer José Luis Rodríguez.

14. The Mexicali Valley includes the valley of San Luis Rio Colorado, Sonora.

15. Unless otherwise stated, monetary figures are expressed in U.S. dollars.

16. This statement does not take into consideration the Santo Domingo Valley, which presents different characteristics.

Copyright © 2006 - 2009 PROFMEX. All rights reserved |