|

||

Mexico and the World

MERCOSUR, the Southern Cone's emerging trade bloc was only in its formative phase at the time FTAA was announced in 1994. Members of this union have ambitions of eventually evolving into a full-fledged common market. As such, this trade bloc presents competition for NAFTA and FTAA within the Western Hemipshere. Trade ministers from MERCOSUR's member countries have been negotiating as a unified bloc at FTAA meetings since 1997 on issues of common concern such as farm subidies and intellectual property. Brazil, the largest member of MERCOSUR has led a move to stall FTAA negotiations while the southern market consolidates. Presidential elections in Argentina and Uruguay in late 1999 demonstrated strong public support for politicians in favor of strengthening MERCOSUR.85 MERCOSUR is an acronym for Mercado Común del Cono Sur (southern cone common market). It was created in March 1991 under the Treaty of Asunción signed by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. All totaled, MERCOSUR’s population is approximately 213 million and its gross domestic product (GDP) in 1998 was $US1.11 billion. It is regulated by an intergovernmental structure that oversees the reduction of common external tariffs amongst member countries. Key sectors such as services, banking, and the free movement of labor currently remain outside of the MERCOSUR’s authority as they are still being negotiated.86 This trade bloc is a result of trade negotiations between Argentina and Brazil in the 1980's. Following the return to democracy, both countries were interested in exploring new ways to manage their outstanding foreign debts, find industrial complementarity and promote technical cooperation between their economies. A series of trade treaties signed in 1986, known collectively as the PICAB Treaty (Programa de Integración y Cooperación Argentino-Brasileño) created a binational decision-making body. This new structure was responsible for reaching additional agreements on economic, military, technical, and nuclear issues. Among these was the 1988 General Treaty for Integration Cooperation and Development that proposed the establishment of a joint economic community by 1998. This period of integration was shortened in 1990 by agreement between Presidents Carlos Saúl Menem and Fernando Collor de Mello. Both leaders also decided to invite neighboring Paraguay and Uruguay to join their next accord. The Treaty of Asunción was signed in March 1991 with the understanding that MERCOSUR would come into existence in 1994.

Third, the region has been coping with an economic

recession that began when Brazilian financial markets plummeted in response

to fluctuations in the global economy. The Russian economic crisis

of 1998 caused investors in emerging markets around the world to withdraw

their capital. Economic problems in Asia compounded the situation,

causing capital flight from Brazil at a rate of $280 million a day by November

1998.92 By the spring of 1999, Brazil’s

instability had begun to have a negative effect on Argentina. To control

the economic crisis, Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso negotiated

a strategic privatization package that included a $42 billion loan from

the International Monetary Fund (IMF).93

As Argentine Trade Secretary Alberto de las Carreras noted, the crisis

forced MERCOSUR to "its most difficult point since its creation.”94

Today, the economies of member nations are on a cautious path to recovery.

Courting Both U.S. and European Trade MERCOSUR's growing international clout since the mid-1990's has raise concern among American policymakers. Henry Kissinger believes that it is a mistake for U.S. foreign policy to ignore this new union. He has chastised American politicans and diplomats “retreating from its own initiatives,” including FTAA and Fast-Track Authority. He warns that “if U.S. policymakers continue to ignore Latin America’s attempts to transcend the nation-state, they will evolve to their own rhythm without reference to a larger hemispheric structure” or U.S. interests.95 Kissinger’s position is based on the premise that a strong MERCOSUR will damage FTAA and American hegemony in the Western Hemisphere. It is not based on economic facts. Trade statistics demonstrate that U.S. exporters have been the main beneficiaries of the trade bloc’s growth. MERCOSUR’s growth has resulted in an increased demand for U.S. exports. As Figure 5 indicates, U.S. exports grew 228% from US$ 10.7 trillion in 1991 to US$ 24.4 trillion in 1998. In contrast, U.S. imports from the region were not nearly as high, rising from 142% from US$ 10.3 trillion in 1991 to US$ 14.6 trillion in 1998. The difference in trade has created a balance in favor of the United States. To date, MERCOSUR officials have side-stepped

the issue of U.S. hegemony in the Western Hemisphere. With the United

States hamstrung by lack of Fast-Track Authority, MERCOSUR has proceeded

to develop new relationships with the European Union, its second largest

trade partner. Both parties are interested in expanding their trade

and are in the process of negotiating an EU-MERCOSUR trade agreement.

Representatives met in Rio de Janeiro in June 1999 to discuss a future

accord, “based on respect for democracy and human rights, sustainable development

and a determination to stamp out trade in illegal drugs.” Although

the summit ended without any final conclusions due to the ongoing Braziilan

financial crisis, representatives did set the framework for continuing

talks. All parties agreed that there would be no possibility of tariff

cuts until mid-2001 and that any forthcoming free trade arrangement would

take effect over a 10-year period.96

Ever mindful of the U.S. Monroe Doctrine warning against European intervention

in the Western Hemisphere, the Europeans diplomatically stated that a future

accord would had no intention of competing with the United States

or FTAA. Clearly, both the EU and MERCOSUR look forward to closer

economic cooperation including new investments in MERCOSUR from Spain,

Italy, and Germany.

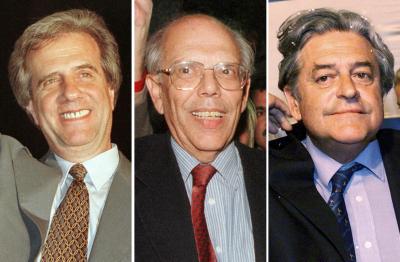

Argentina's Changing Foreign Trade Policies (1983-1999) In October 1999, Argentina elected a new President for 1999-2003. Fernando de la Rua is a fiscal conservative from the center-left Allianza party (also known as Unión Radical Cívica) who campaigned to crack down on graft and corruption. Prior to his election as President, he was opposition leader and mayor of Buenos Aires. His campaign slogan “return Argentina to dignity” referred to alleged corruption in the Menem administration.

The Allianza party was ousted from power when Peronista nominee Carlos Saúl Menem was elected President in 1989.97 He served two successful terms from 1989-1995 and 1995-1999. During his tenure, he concentrated on liberalization, deregulation, and privatization. In 1991, his government brought inflation under control with “convertibility” reform. At the same time, Menem resolved that he would repair Argentina’s standing in foreign affairs by concentrating on two foreign relations priorities:

Traditionally, Argentina had always seen itself as a world power and competed with the United States for hegemony in the Western Hemisphere. Menem defied a hundred years of Argentine foreign policy tradition when he acknowledged that Argentina would accept the world power structure “as it exists, rather than as Argentina would like it to be.”98 He openly supported U.S. initiatives in the world arena including the Gulf War and FTAA. At the end of his second term, Menem proposed elevating Argentina’s relationship with the United States to a new level of inter-dependence suggesting the nation dollarize the peso. Menem’s dollarization proposal was based on the success of his “convertibility” monetary reform policy. To control the inflation that had overtaken Alfonsín’s administration, Menem authorized Argentina’s currency board to limit the stock of hard-currency reserves in 1991. Convertibility made it more difficult for investors to withdraw their capital. At the same time, the government was prohibited from easing monetary policy or devaluation. In general, the reforms eliminated hyperinflation and stimulated growth.99 Under Menem’s leadership, Argentine economy’s boomed with growth rates of 9% in 1996-1997.100

Argentina’s dollarization proposal was based on

Menem’s opinion that the dollar should become a regional currency like

Europe's new euro. Conceivably, this would happen if Argentina, Brazil,

and Mexico converted to dollars. Carlos Fedrigotti, president of

Citibank in Argentina, viewed Menem’s suggestion as a “shocking novelty.”

At the Federal Reserve, Chairman Alan Greenspan expressed disinterest and

skepticism. Argentines in the private sector received the proposal

with apprehension. Discouraged by the reception of his idea, Menem

concluded in the final days of his Presidency that “dollarizing is long-term

project, not crisis management and it will require not just the agreement

of the United States, but also a consensus in Argentina.”103 While Menem worked arduously to strengthen this relationship, De la Rua will most probably implement a more traditional Argentine position of non-alignment.104 He is also likely to support strenthening MERCOSUR rather than push for implementation of FTAA. MERCOSUR Trade

- The Catalyst of Uruguayan Poltics

Prior to this election, Uruguayan politics had been characterized by power sharing between the rival Colorado and Blanco parties. Following the end of military rule in 1985, Colorado nominee Julio Maria Sanguinetti was elected President for a five-year term. As a centrist, he implemented policies that were primarily aimed at reducing inflation. Conservative Blanco candidate Luis Alberto LaCalle succeeded Sanguinetti from 1990-1995. LaCalle’s primary policy objectives were privatization and reducing the role of the state in the nation’s economy. His ambitions were thwarted by a successful national plebiscite, which demanded that certain key sectors remain under government control. As a result, the 1994 election was closely contested. Sanguinetti narrowly won a second term in office from 1995-1999. During his second administration, he made moderate efforts to encourage a market-oriented economy. He balanced privatization with an increase in education spending and reform of the social security system. As evidenced by the closeness of the 1999 election,

Uruguay’s major concern is the stability and expansion of MERCOSUR.

Statistics in Tables 14 and 15 demonstrate that Argentina and Brazil are

more important trading partners than the United States, Europe, or Asia.

Commerce with neighboring Argentina and Brazil accounts for approximately

40-45% of Uruguayan trade.110 American-Uruguayan

trade, even through it has a slightly negative balance in favor of the

U.S., totals less than 10% of Uruguay’s international commerce. MERCOSUR’s

success is of paramount importance to the Uruguayan economy. It is

unlikely that in the future, Uruguay will support FTAA if this means a

reduction in MERCOSUR's strength and international clout.

Next

Section 85 Kevin G. Hall, “Economic Woes Drive MERCOSUR to Clean Up Its Own House,” Journal of Commerce, 12 March 1998 and Jason Webb, “34 Nations in Americas Seek Free Trade Zone,” Washington Times, 18 June 1998. 86 Thierry Ogier, “Complementary Trade of MERCOSUR Thrives,” Journal of Commerce, 12 March 1998; Jason Webb, “34 Nations in Americas Seek Free Trade Zone,” Washington Times, 18 June 1998; Organización de Estados Americanos, Sistema de Información al Comercio Exterior, Acuerdo del Mercado Común del Cono Sur (MERCOSUR), [1995-99] <http://www.sice.oas.org/trade/mrcsr/mrcsr1/htm>; and Embajada de Uruguay en EEUU, translation of “MERCOSUR and its Origins” El País [Montevideo] [1996] <http://www.embassy.ury/uruguay/econ/MERCOSUR/merc-002.html.>. 87 Ogier,“Complementary Trade of MERCOSUR Thrives,” and Hall, “Economic Woes Drive MERCOSUR to Clean Up Its Own House.” 88 For more on this international environmental coalition and its objectives see Coalizão Rios Vivos [1999] <http://www.riosvivos.org.br/>. 89 “Brazil Pulls Out of Destructive Project in Wetlands,” Environmental Defense Fund Newsletter, June 1998 <http://www.edf.org/pubs/edf%2Dletter/1998/jun/c%5Fbrazil.html>; Secretaria Ejecutiva C.I.H., Hidrovía Paraguay-Paraná [1999] <http://www.ssdnet.com.ar/hidrovia/index1.htm>; International Rivers Network, The Paraná-Paraguay River Campaign [September 1999] <http://www.irn.org/programs/hidrovia/index.html>; and Conservation International, Hidrovía Development Project [1998] <http://www.conservation.org/RAP/Aqua/PRIORITY/SITES/PANTANAL/Hidrovia.htm#hidrovia>. 90 "MERCOSUR Leaders To Lick Wounds But Speak Bravely," CNN, 11 June 1999. 91 Raúl Cubas Grau is a member of the National Republican Association (ANR, also known as the Colorado Party). He won a five-year term as President on May 10, 1998 with 53.74% of the vote. Argana became Vice President when former Army Chief Lino Oviedo, an ally and mentor of Cubas, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for attempting to oust sitting President Juan Wasmosy in 1996. Oviedo had defeated Argana in a party primary. For more see International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES), 1998 Election Guide [1999] <http://www.ifes.org/eguide/elecguide.htm>; “Paraguay Hunts For Vice President's assassins,” CNN, 23 March 1999 <http://cnn.com/WORLD/americas/9903/23/paraguay.attack.03/index.html>; “Impeached Paraguayan President Calls It Quits,” CNN, 28 March 1999 <http://cnn.com/WORLD/americas/9903/28/paraguay/index.html>; “Paraguay Gets New President As Military Leader Flees To Argentina,” CNN, 29 March 1999 <http://cnn.com/WORLD/americas/9903/29/paraguay.01/index.html>. 92 David E. Sanger, “Brazil is to get IMF Package for $42 Billion,” New York Times, 13 Nov. 1998. 93 Hall, “Economic Woes Drive MERCOSUR to Clean Up Its Own House;” Kevin Hall, “Crises Dim Prospects for Americas Free Trade,” Journal of Commerce, 5 Feb. 1998; and "MERCOSUR Leaders To Lick Wounds But Speak Bravely," CNN, 11 June 1999. 94 Up until the Brazilian IMF crisis, the IMF and US Treasury had only stepped into help countries when they were on the brink of default. When the Brazilian financial package was authorized, Brazil still had $40 billion in reserves at the IMF. The $42 billion to stabilize the Brazilian economy came from a U.S. loan to the IMF. Of the $42 billion, $5 billion was US taxpayer money. Instant access to the funds was granted based on the condition that the Brazilian government would immediately approve key administrative reforms. David E. Sanger, “Brazil is to get IMF Package for $42 Billion,” New York Times, 13 Nov. 1998. 95 Henry A. Kissinger, “Expand Free Trade to All Western Hemisphere,” Los Angeles Times, 27 April 1997. 96 Peter Muello, “Rio Summit Leaders Regulate Capital,” AP, 26 June 1999. 97 In 1995, Menem received 47.49%

of the vote. He defeated José Octavio Bordon representing

a leftist coalition that included Frepaso (25.2% of the vote) and Allianza

(Union Cívica Radical) candidate Horatio Massaccesi (17.1% of the

vote). International CNN Election Watch, Argentina [1999] <http://www.cnn.com/WORLD/electon.watch/americas/argentina.html>. 99 Under this new system, Argentina was severely tested during the 1994-1995 Mexico devaluation crisis. Numerous Argentine banks defaulted, decreasing their total number from 2000 to approximately 140. Menem’s banking reforms encouraged acquisitions by foreign banks who supplied new capital for investments that stimulated record economic growth. Foreign banks now hold approximately 50% of all bank deposits in Argentina. Douglass Stinson, “Staking Out the High Ground,” Latin Trade, November 1998, 44; and "Argentina Down To Earth," The Economist, 15 May 1999. 100 In 1998, as result of the Brazilian crisis, Argentine growth decreased to 4.3%. U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook, Argentina [1999] <http://www.odce.gov/cia/publications/factbook/ar.html> 101 Menem was particularly interested to know if the Federal Reserve would agree to be the lender of last resort in case an Argentine bank should fail. He also wanted to know if the United States would compensate the Argentine Central Bank for the US$750 million it would lose annually in interest earned from the U.S. Treasury bills if it converted to dollars. "Argentina Down To Earth," The Economist, 15 May 1999. 102 Julia Preston, "Mexico Measures Identity in Pesos vs. Dollars," New York Times, 16 May 1999; and Clifford Krauss, "Buck Doesn’t' Stop: Now Argentina May Adopt It," New York Times, 25 Feb. 1999. 103 Krauss; and "Argentina Down To Earth," The Economist, 15 May 1999. 104 “Argentine Opposition Leader Wins Presidential Election,” CNN, 25 Oct. 1999. 105 “Historia de un Luchador Incansable,” Perfiles, Elecciones ’99, El País [Montevideo], 1 Nov. 1999 <http://www.diarioelpais.com/suplementos3/elecciones99/perfiles/per_colorado.html>. 106 In the legislature, Vazquez’ Frente Amplio increased its representation in the Senate by 13% and House of Delegates by 7% in this election to hold 40% of the 30 Senate seats and 40% of the 99 House of Delegates. CIA, World Factbook, Uruguay [1999] <http://www.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook/uy.html>; “Uruguayan Socialist Calls First-Round Win ‘Historic’ Runoff Looms,” CNN, 1 Nov. 1999. 107 Luis LaCalle, nominee of the center-right Blanco party received 21% of the vote and was eliminated from the November run-off election. “Exit Polls Show Leftist Leading In Uruguay,” Washington Post, 1 Nov. 1999. “Uruguayan Socialist Calls First-Round Win ‘Historic;’ Runoff Looms,” CNN, 1 Nov. 1999; and Elecciones ’99, El País [Montevideo], 1 Nov. 1999. <http://www.diarioelpais.com/suplementos3/elecciones99/> 108 Vazquez faced charges accusing him of using his position as Director of Radiology to recommend that INDO purchase computer equipment from his son’s company. Vazquez denounced the judges reviewing his case noting that the charges had been filed two years prior and legal review had been delayed to thwart his political career. "Lacalle Dijo Que La Respuesta De Los Votantes Blancos Fue El Mejor Elogio Para La Decisión Del Directorio - Hemos Sido Determinantes,” El País [Montevideo], November 1999, <www.diarioelpais.com:82/suplementos3/elecciones99/index.phtml?noti=6>; and “Tabaré Vázquez Acusado Corrupción,” El Mercurio Electrónico [Santiago, Chile], 8 Oct. 1999. 109 “Socialist Concedes Uruguay's Presidential Race To Ruling Party,” AP, 28 November 1999; Clifford Krauss, “Governing Party Candidate Wins Presidency in Uruguay,” New York Times, 29 November 1999, <http://www.nytimes.com/library/world/americas/112999uruguay-vote.html> 110 CIA, World Factbook, Uruguay [1999] <http://www.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook/uy.html> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © 2000 - 2009 PROFMEX. All rights reserved