|

||

Mexico and the World

Dangerous Journeys: Chapter published in

Driving over the crest of a low rolling hill as the first sunlight of the morning began to break across the highest points of the landscape, I could see a valley ahead at a lower elevation that was filled with early morning fog. Only a far distant church steeple and the tops of a few other rolling hills with scattered trees stood out above the mist. As the car dipped down into the fog, reminiscent of an airplane diving into a cloud, everything turned dark again. After a few kilometers, dark shadows of what turned out to be men, women, children, and an occasional horsemen appeared as gray ghosts along the roadside, all heading in the same direction that I was driving. I could now see that the sun was beginning to burn its way through the ground fog that was slowly beginning to rise as it was warmed by the sun. The walking figures began to increase and then to merge with two other streams of people and animals moving toward an intersection, where a cobbled road turned left and disappeared back into the mist. My traveling companions were still asleep, as I instinctively turned left to join the slow stream of people with loads on their backs, horseback riders, and a few heavily loaded horse- and cattle-drawn carts. Our open car—idling along at the speed of the walkers—was the only non-traditional means of transportation in this expanding flow of travelers, and it seemed as though we were invisible to everyone else, since no one looked at us or made any attempt to move over to let us pass. Not that I wanted to pass. It was exhilarating being part of this extraordinary procession in the mist.

Within minutes I also began to hear a church bell ringing in the distance. With the sun rising in the direction we were headed, the fog began to break up rapidly with rays of sunlight penetrating through and falling onto the travelers and the still damp roadway. The rounded shapes of the cobblestones glistened as the light rays bounced off them and into my vision. Looking directly toward the sun through the mist created a perspective of penetrating light rays that was very powerful. This scene with rural Tarascan Indians wearing broad-brimmed sombreros, ponchos of muted natural colors over white outfits and huaraches on their feet, slowing walking toward those rays of light accompanied by the sounds of a distant bell and the clatter of horseshoes and metal cart wheels on that cobbled roadway, is a picture that will be etched forever into my memory. As I glided almost silently through this scene, I felt the magnetic pull of the Mexican landscape, its people, and its history on my soul, and it has never left. I vividly remember to this day my feelings of awe and appreciation of the scene I was witnessing. Five of us were driving from northern California on our way to Mexico City College in September 1956, and this had been my first real encounter with a Mexican village. We had entered Mexico at Nogales in a yellow 1940s convertible pulling a small trailer. It had taken three days to drive the west coast highway to Guadalajara, where my brother and I and three companions had an evening of celebratory carousing in a mariachi-laden nightspot. I had decided not to drink and to watch over our group. Since we were behind schedule, we set out in the middle of the night after closing time on old Route 15 heading toward Morelia and Mexico City. Somewhere in the state of Jalisco, south of Lake Chapala near Tuxcuenca, or perhaps across the border in the state of Michoacán, I first experienced “Village Mexico.”

Village Mexico was still a strong reality in the 1950s. At that time there were very few cars and trucks on the roads, and nearly three out of every five of all Mexicans lived either in rural villages with populations under 2,500 inhabitants (51 percent) or dispersed on the rural landscape in isolated homesteads (7 percent). Throughout most of southern “Mesoamerican” Mexico, close to 80 percent of the people lived rural lives in the 1950s—not greatly changed from the 90 percent who were rural in the entire country when the Revolution began in 1910.

Time and Place in Mexico in the 1950s

I have thought about that initial event many times over the last half century, wondering if I could return and find that place. But I never traveled that particular road again, and I never returned to that village. I do not even know its name. Thus one of my earliest and most powerful memories of Mexico is also one of my most illusive, in that I was never to repeat that first dream-like experience with village Mexico in the same way.

But, of course, that village scene at present is exceedingly rare in Mexico, although I still know a few remote places that represent an earlier landscape and time. Today, villages that had 2,000 people in the 1950s are mostly urban centers of 20,000 or more. The population of Mexico rose four-fold between 1950 and 2000 to nearly 100 million, with nearly half the population of the country living in the 26 largest metropolitan areas. Mexico City’s current extended metropolitan population of nearly 25 million equals that of all of Mexico in 1950, while the percentage of those dwelling in rural villages has dropped to only 15 percent—fewer than one person out of every six.

Appreciating a “sense of time and place” in Mexico has both personal and intellectual aspects to consider. My brother and I had an apartment on the Paseo de la Reforma near the corner of Río Neva in 1956-57. That first fall term I spent a lot of time in the afternoon studying outside on the old stone benches along the Reforma. Traffic along the Reforma in September 1956 was virtually non-existent compared to the present, and the greenery and trees on the broad islands along either side of that great boulevard were ideal places to read, study, and people-watch at the same time. In those days well-dressed horseman wearing large Mexican sombreros would still pass by occasionally on the hard-packed earth pathways that today are tilled and covered. When I had time to break from my studies, I read books about the historical events that occurred in Mexico City, many of which turned out to have taken place along the Reforma. While reading Prescott’s book on the Conquest of Mexico, I envisioned how Cortez and his men fought their way out of Tenochtitlán, the island Aztec capital on what is now called Lake Texcoco, along the southern causeway very close to where I sat reading. I also read books on the U.S. invasion of Mexico under General Scott in 1848—only a century before—and how his men fought up the Reforma to capture Chapultepec Castle from the “Niňos Heroes.” I remember how extraordinary it felt to be reading at the precise place where history had been made in the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Little did I know then, that two blocks away from where I sat thinking about those earlier events, Ché Guevara was living with his Peruvian-born wife, Hilda Gadea Acosta. Their apartment was at 40 Calle Nápoles, Apt.5, near the corner of the block with Calle Hamburgo in the Pink Zone. Between September and late November, Fidel Castro and his lieutenants came to his apartment from time to time to plan the invasion of Cuba. On many occasions during that fall, I played pool with my friend Murray in a second story pool hall on the corner of that block, not knowing what was happening in the building next door in Ché Guevara’s apartment.

History seems to remember those events of the past that involve conquest, invasion, revolution, death and destruction. Clearly those are turning points in history when societies are going through dynamic periods of upheaval and change. In my case, I do not think that I was drawn to the violence of those events, but more to the drama in the clashing worlds of ideas, ideologies, and often completely different “world views” of the combatants. My point in telling the previous story is that I was caught up with being at “the place” where two major “turning points” in Mexican history had occurred—the Conquest of the Aztec by Cortez and his men and the U.S. invasion and conquest of Mexico City and Chapultepec Castle that I could see just down the Reforma from where I sat reading. But I was completely oblivious to the history that was going on virtually under my feet with regard to the Cuban Revolution.

The irony of those events helps to point out what I feel is one major element of life in Mexico—that one is surrounded at all times by a sense that the “unexpected” can occur at any moment, and that often there is a sharp contrast between the surface appearance and the reality, and sometimes very different events happen simultaneously in the same place at the same time—each unrelated to the other. This concept can be called “unexpected juxtaposition of events”—historically, as in the above case, but also when viewing life in the city. Some of these daily events would be considered once-in-a-lifetime occurrences in the States. Surviving the volatility of unexpected events was a skill that Mexico City College students were forced to hone and bring into play, if not daily, then quite frequently. Even though danger and the possibility of death were in the air at all times, I do not remember my friends worrying about it. It was just a fact of life, as were the realities of the potential for natural disasters of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

Regarding the latter, I always felt that the title “Under the Volcano” [from James Lowry’s book in the 1940s] best captured the feeling for me of my time in Mexico. In the late 1950s it was still possible to see clearly Popocatépetl and Ixtaccihuatl virtually every day, and we even climbed them along with other mountains and volcanoes. But the concept of a “volcano” was also a metaphor for life in Mexico City and the countryside, where the most peaceful scene could suddenly explode into fast and furious action and sometimes violence and death. A number of friends and acquaintances died or nearly died in Mexico at that time. There was a saying at the time, that “half of the students will probably go on to get Ph.D. degrees and something bad will probably happen to the other half.

A Brief History of Mexico City College

The life of American students at Mexico City College in the mid-1950s to the early 1960s was one of constant excitement in a multi-dimensional world of cultural diversity, an ambiance of sights, sounds and color, and most of all opportunities for adventure. The orderly, linear expectations of family, friends, and community that often directed one’s life path at home—school, girlfriend, marriage, children, car, home, job for life, grandchildren—were dramatically altered in a number of ways once one entered Mexico. One of those twists was that in Mexico people are most often respected and honored for what makes individuals different and unique—in contrast with life in the States during in the 1950s where people were most often respected and judged by how much they conform to a common ideal and how well they fit in as a “member of the group.”

A second important factor was that nearly half of the Mexico City College students were military veterans of World War II, the Korean War, or occupation duty in Japan or Europe. These ex-GIs were sophisticated, somewhat jaded, and they desperately wanted to avoid the “bland” college experience in the States often dominated by fraternities and sororities that was so appealing to younger students directly out of high school. Most ex-GIs were mostly between the ages of 25 and 35, and most had experienced the world in times of turmoil. These veterans thrived in the diversity and excitement of the Mexican cultural environment that they found at Mexico City College, and in the international life style of one of world’s oldest and grandest cities. Some of these GI veteran expatriates were developing skills as writers, artists, and critics, and since Paris of the 1920s no longer existed, these veterans were searching for that kind of ambience and life style. In many ways, Mexico in the 1950s felt frozen somewhere in time between the two world wars. The Mexican Revolution of 1910-25, with sporadic conflicts up to 1940 or so, had put modernization into a holding pattern throughout the country. Parts of Mexico City located between Chapultepec Castle and the Central Zocalo had recognizable elements of Paris in the 1920s—more so than in any other Latin America city except Buenos Aires. For many of the intellectually oriented veterans and students at MCC, this was potentially the new Paris, where ideas, art, literature and revolution could be discussed in cafes, taverns, and at numerous and risqué parties where inexpensive liquor and “Acapulco gold” could be found.

The ex-GI veterans made up between 40 and 50 percent of the student body at Mexico City College, but they were far from being a homogeneous group. Aside from being mostly male and 10 to 15 years older, they were as diverse in their aspirations and life styles as the rest of the student body. In attempting to assess the different subculture groups at the college, I need to define the group in which my brother Jim and I fit most closely. We were among a group of students who came to explore new worlds, to discover new ways of seeing and thinking, to help open new roads to remote places, to climb snow-capped volcanoes and explore all of southern Mexico, to feel the historical and artistic heartbeat of Mexico, and to do it with companions who thrived in the extraordinary milieu that existed there at that time. Having the chance to live and study in Mexico City was adventure enough, but when all the natural and human landscapes of southern and central Mexico became part of the experiential classroom, the education that each of us received went far beyond anything most of us had anticipated. Other subgroups of students at the college will be discussed later.

Mexico City College was unique because it was the only American liberal arts college south of the Rio Grande, and one of only several in the world in the 1950s. Students at MCC frequently discussed the only other options—Sofia University in Tokyo, Japan and the American University in Beirut, Lebanon, but because of distance and cost those academic institutions were only something for most of us to fantasize about. Mexico City College had it all—not too far from the U.S., moderate costs, MCC was a member of the Association of Southern Universities (so that credits transferred easily to the States), and most of all, Mexico was a fascinating and inspirational place to be. While Mexico had a dangerous and volatile element to daily life, there was also a sense of “power of place in the landscape and people that could not be matched anywhere else at that time.

Mexico City College was quite young, even younger than I was as an 18 year-old freshmen in Fall Quarter, 1956. Henry L. Cain and Paul V. Murray had founded the college in 1940 in downtown Mexico City with a nucleus of five teachers, six students, and no books. The college grew beyond its earlier scattered buildings in downtown Mexico City and in 1954, it had moved to a new campus with room to expand on the site of an old country club located west of downtown Mexico City on the road to Toluca at kilometer 16 on Highway 15. By the late 1950s its most well known departments were anthropology, archeological field studies, art, creative writing, international relations, business administration, and Latin American Studies. Alumni records for the 11 years from1947 through 1957 show that MCC confirmed 1,113 Bachelor’s degrees and 273 Master’s degrees, a yearly average of 126 degrees—101 BA’s and 25 MA’s (Journal of Collegiate Registrars, Vol. 33, No.3, Spring 1958). It should also be noted that in 1957 the college opened a branch campus student center for field studies in Oaxaca City in the state of Oaxaca, which was called the Centro de Estudios Regionales.

For those of us who look back on the Mexico City College experience, the mid- to late-1950s and into the early 1960s are seen as the “golden age” for the American students. The decline of MCC began in early 1961, when it was discovered that the business manager had absconded with large sums of money from the college, throwing the future of the college into sudden disarray. At that time the college had over a hundred faculty members, a regular student body of nearly six hundred (it would go to nearly 1000 during the college exchange programs during winter and summer quarters from such academic institutions in the U.S. as Ohio State, Michigan State, and the University of Washington), and a library with nearly 30,000 volumes. So with the major loss of its operating funds, Old Mexico City College never really recovered from that major financial crisis that threw the administration, faculty and students into turmoil.

In 1963 as part of the resolution of the college’s unstable financial situation, the name of the college was changed to the University of the Americas and the campus made a third move—this time in 1970—east of Mexico City to Cholula in the state of Puebla. The old MCC students had the fortune to be there at a time in the 1950s when an international student body from more than 20 countries, nearly all U.S. states (California frequently had more than 100 students) and from throughout Mexico could get a full four-year undergraduate or graduate education in the humanities, social sciences and fine arts. That dream faded, and then virtually disappeared after UDLA moved to Puebla. Only a decade and a half after the glory years of Mexico City College in the 1950s, the new president of the La Universidad de las Americas, Ing. Macías Rendón, moved quickly to transform the university into a technocratic institution that more nearly approximated job training for engineers than one of true liberal arts education. During Rendón’s first year, 1975-76, the new president openly indicated that the new policy of UDLA was to replace faculty with Ph.D. who do research with holders of B.A. degrees who will only teach. In mid-March 1976, Rendón fired 24 of the 110 member faculty without due process, including distinguished professor of biology, Dr. Paulino Rojas, who was replaced by a young man who failed to earn his B.S. degree at the University. At the same time, Ing. Rendón announced the elimination or deep cut of much of the undergraduate and graduate studies programs in the arts, humanities, anthropology, and Mexican history portions of the academic structure, so that the institution could focus on a more technocratic (and non-intellectual) approach to higher education. The final death of the ideas behind the old Mexico City College, and the academic battles that went on over the next decade or more in an attempt to resurrect them, will not be covered in this study. What will be noted is that the old Mexico City College—as it existed as a liberal arts college at kilometer 16 on the Toluca highway between 1954 and 1963—had completely disappeared by the end of 1976.

Impressions of Mexico City College

Most students living downtown in Mexico City caught the MCC school bus behind the fountain of Diana, the Huntress that was located in the center of the circular glorieta where the broad avenue Paseo de la Reforma angles west and Chapultepec Park begins. The bus was parked between two enormous black-colored lions on pedestals, each the size of a Volkswagen car. These lions sat on either side of the road that continued up a short distance to Chapultepec Castle, and which had a commanding perspective looking straight back down the Reforma toward the center of the city. The MCC bus departed every half hour from the “liones”, passing through a corner of the park, past the massive monument to the 1938 nationalization of foreign oil companies by President Lazaro Cardenas, and then through the palatial Lomas de Chapultepec district. Following a curving and slowly rising roadway with trees and greenery in the median and on both sides of the road, the highway rose up a ridgeline, flanked by barancas on both sides, and ultimately to the college at kilometer 16 on what was referred to as the “Toluca Highway.” Those 10 miles trips every school day gave the students time to shake the late-night cobwebs from their minds, and make the transition to an entirely different world up above the teeming city.

From the college there were magnificent views of the city to the east, the wooded barranca below the college, and on most days, the volcanoes Popocatépetl and Ixtaccíhuatl to the far south, which stood out against the horizon at elevations just under 18,000 feet. The campus had taken over a former country club, so a number of buildings were already in place, including the two-story building housing the cafeteria, theater, and art department. The cafeteria opened on to large open patio that projected out into the upper parts of old spreading eucalyptus trees from the slope below, with a lovely view south. On campus, the tiled mosaic murals on the walls of many of the open-air classrooms, along with the green, finely-groomed campus with open patios and clusters of stone seating for outdoor seminars, gave the campus a strong aesthetic sense of belonging in that location. It fit with everything else around it along a beautiful wooded ridgeline rising to the west toward Desierto de los Liones [Desert of the Lions] National Park. Beyond was the pass to Toluca and its glorious Friday market. Everything about the place felt right.

Some Classroom Experiences at Mexico City College—1956-1958

What stands out when thinking about courses at Mexico City College, is the range of unusual, and sometimes bizarre, professors who taught there. Most of them were extraordinary individuals whose life experiences went far beyond that of faculty one would find in institutions of higher learning in the States. I later had excellent professors at the University of Washington, but they generally did not add the layer of worldly-wise experience to their courses in ways that the MCC faculty did. Teaching in Mexico was chosen more for the life style, love of the place and research possibilities than for financial gain. A number of MCC faculty members had other jobs in the city and taught almost for the joy of doing it; some were ambassadors from other countries who liked the idea of teaching. One that stood out for me was Dr. Pablo Martinez del Río, from the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History, a famous anthropologist in his 70s with sweeping gray hair, and typically wearing a baggy black suit with tie, a black-felt hat and white spats over his shoes. I still keep and cherish my lecture notes from his course on the Indians tribes of Mexico. He must have known more about the topic than anyone alive.

One of the first classes I attended was an economic geography course taught by a Mexican army officer—Colonel Carlos Berzunza—who seemed to think he was Napoleon. He was very short, barely over five feet, and smoked a big cigar during his lectures. Sitting next to me on the left was a bearded, long-haired American student wearing a colorful Mexican poncho, along with open-toed huaraches on his feet. He had a gold colored ring in his earlobe, and a parrot was sitting on his right shoulder. I doubt whether anyone attending college at home in the states at that time looked anything like him, but a decade later by the mid-1960s this student would have fit into many U.S. academic institutions during the early “hippie” years. The classroom we were sitting in had open windows on opposite sides and its door opened onto a big patio with the backdrop of Mexico City beyond. This setting was vastly different from my high school classrooms in Boise, Idaho.

Col. Berzunza paced back and forth with big fast steps in front of the class as he lectured without notes while munching his cigar. After every half dozen trips back and forth across the room, he would continue right through the door a dozen paces or more and stand lecturing to the class from the patio, while looking out over the city. All we could see was his back and his wildly gesturing arms, while the cigar shifted from hand to mouth to hand with an occasional pause followed by a cloud of smoke. We were never certain whether he was lecturing to our class or to the populace of Mexico City. It was hard enough following his lectures in English with his accent and the cigar, but it became very difficult to follow what he was saying at such a distance. No matter—the class loved his showmanship. We all just strained a little harder to hear him as we leaned forward on the edge of our chairs.

Professor Willis Austin was my English Literature Professor, who along with his wife and young son, my brother had gotten to know the previous year. My course with Austin had only eight or nine students and was taught in a room of a house where one door opened to a kitchen. Austin had a strong fondness for drink, often taking a short break to disappear into the kitchen for a slug of scotch or rum (the popping of the cork was the giveaway), and wiping his wet beard with the back of his hand as he returned. Austin held his liquor well, and it even seemed to spice up his quotes from English writers, especially one of his favorite poets, A.E. Houseman. We often met Austin and other friends for afternoon drinks downtown where everyone talked of literature, art and current world events. One of his friends—a Mexican writer who grew up in Paris and spoke French, Spanish and English equally well—was seriously involved in bull fighting and tried to convince me to join his bull fighting friends for their weekly training sessions. After noticing nasty scars on his arm and neck, I prudently decided that I already had too many activities during my first term of studies.

My second English Literature course that first year was with Professor Claire Bowen, who oversaw production of the college newspaper—the Mexico City Collegian. The class was small—only seven students—and it was a wonderful course. We had a major problem, however, but it was not anything the professor could control: three of the seven students in the course died violently during that short 10-week quarter. The first to go was a young man in his mid-20s from Wyoming, who drove a fancy red sports car convertible. It was said that earlier that year his father had died and left him a million dollars, so he set off to Mexico for college. One afternoon he backed out of the narrow parking lot in front of the entrance to the college into the path of a runaway bus—an infamous “Toluca Rocket” overloaded with people, purchases and livestock—that was unable to stop, and with “screeching” nonexistent brake pads grinding against metal, slammed into his low-slung car and he was beheaded. The second student to die was a handsome young man from New York City who was one of the editors on the school newspaper—the Mexico City Collegian. According to his friends, while in Acapulco during a long weekend break, and somewhat despondent from losing his girl friend, he decided to swim to China after an evening of drugs. Needless to say, he did not make it.

The final classmate to die failed to return from a Thanksgiving week trip to Acapulco. He had gone to the famous bar, Río Rita’s, in the red-light district with friends. Sometime around 2 am, when the student was totally drunk, he left to sleep in the back seat of their parked car outside the nightclub in a tough district of town. When his friends finally left Río Rita’s a few hours later, the car was gone. The stranded students had to return to Mexico City the next day on a bus. A week later the car was found about 50 miles from Acapulco on a side road over a cliff and burned to a shell, with the charred body of our classmate inside. The police said it was an accident, but his friends said that it had to be murder. They never found his wallet or any of the things that were in the car. During the last class in that course the four of us who were still alive looked at each other with relieved eyes—we had survived.

In spring quarter 1958, I was in a sociology course taught by Morton Sloane, when he took us to visit the Distrito Federal Penitentiary at Lecumberri—“el palacio negro” [the black palace]. My strongest memory from the visit was the 30 minutes that our small group spent talking with and interviewing Ramón Mercados (Mercader) del Rio—the Spanish communist who killed the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky (age 60) at his home in Coyoacán, a southern suburb of Mexico City. Mercados, acting as the friend of Trotsky’s personal secretary, struck Trotsky in the back of the head with an alpine-climbing axe, and he died the next day—August 21, 1940. Mercados was thought for a time to be a Canadian named Frank Jacson Mornard, but his true identity ultimately came out. Mercados had been in prison for nearly 18 years at that time we talked with him. The longest sentence in Mexico for murder is 25 years, and with only a few years to go on his term, Mercados was cheerful and friendly. He had a corner cell during the daytime by himself, barred on two sides, and he seemed to be friends with a number of passing guards, prisoners, and visitors. At night he had a more private cell.

Our group of about 10 stood next to the cell talking with him as he stood on the other side of the bars, holding them with both hands. He seemed to enjoy the interactions and the discussion in Spanish that was led by Professor Sloane. I later read that he was released two years later in 1960, and was seen boarding a flight to Prague, Czechoslovakia from Paris. Mercados lived in Moscow for a number of years, where he received an “Order of Lenin” award. Many years later in the 1980s he was living in Havana, Cuba, where he died of cancer.

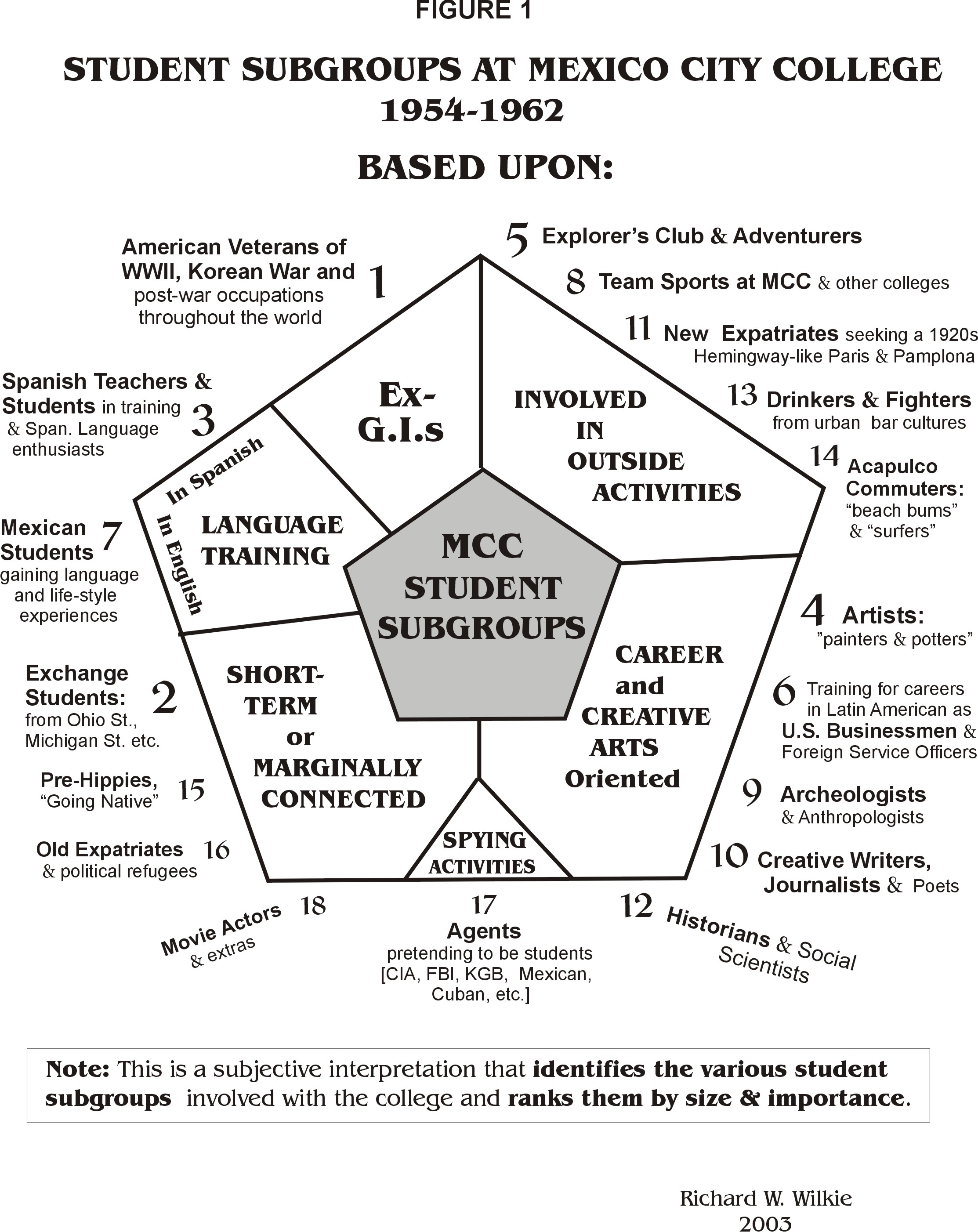

The Mexico City College Student Body

Of the nearly 1000 or so students enrolled at MCC in the 1956-57 academic year, about 400 were U.S. military veterans studying on the G.I. bill. On the 15th day of each month, Salvador López Tello from the Visa Department at the U.S. Embassy arrived at the college to give out checks of $115 to the ex-G.I.s—what they referred to as “life blood.” These older students—most of who had fought in the Korean War, World War II, or both—completely skewed the average age of the students. In class the first day I met Bob Dukes, a veteran from Atlanta who had been a B-29 “tail-gunner” over Japan in WWII. His plane dropped the first supplies to an American POW camp on a mountainside only 12 miles from Nagasaki, where the second atomic bomb had exploded. Earlier in the mountains of Idaho in the late 1940s, I had heard stories about that same camp, and the first supplies that were dropped to it—from Tommy Burke, a friend of my parents who had been captured on Wake Island shortly after Pearl Harbor, and whose physical deterioration in that POW camp led to his early death in 1952.

For me, that link through time and space with Bob Dukes was very meaningful. Not only was I learning to connect to places and events through personal experiences, but also—although once removed—I was connecting to historical events through people I knew, and in this case from different perspectives of the same event. It is a powerful realization that helps to connect people with history and the world, and it is very different from just reading about events in books. Living in Mexico opened the door to these experiences in ways that would never have happened back at college in the states.

American military veterans accounted for between 40 and 50 percent of the students, depending on the academic quarter. Three major groups stood out among the ex-G.I.s, the largest being that of adventurers and drinkers who after a number of years in Europe or the orient could not face the stifling uniformity of life back in the states. The second largest contingent of veterans was made up of the more serious business-school-bound veterans who after learning Spanish and graduating from MCC, often went for graduate degrees at Thunderbird Business School in Phoenix, Arizona, and then dispersed into Latin America with companies like Pan American Airlines, Coca-Cola, and United Fruit. A third, but smaller group, encompassed those veterans who took academic routes to later become teachers or college professors, thus building on international experiences in several regions of the world.

An example of the first group of veterans is found in Jack Kerouac’s novel, On the Road, about adventurers seeking a larger, more experiential life than what they saw in the United States. This important novel captured the flavor of the “Beat Generation” and their flight to Mexico in part four of this road book. The ex- G.I. character in the novel, Stan Shephard, was driven to Mexico City College by the major characters of his novel, Dean Moriarty (really Neal Cassiday), and Sal Paradise (really Jack Kerouac). Although Mexico City College did not play a major part in the book, the group travel was traveling through Mexico so there so their friend Stan could enroll at MCC:

“‘Sal, ever since I came back from France, I ain’t had any idea what to do with myself. Is it true you’re going to Mexico? Hot damn, I could go with you? I can get a hundred bucks and once I get there sign up for the GI Bill in Mexico City College.’ Okay, it was agreed. Stan was coming with me.” (pp. 257-258)

The novel actually took place in 1950 when Kerouac stayed in Mexico City for a time, and was written initially in 1951. From Kerouac’s experiences there, he also wrote, Mexico City Blues, published in 1955, although it had little to do with the place.

Two other large student subgroups included the exchange students who came for a winter or summer quarter—mostly from Ohio State, Michigan State, and the University of Washington and Spanish teachers and students from the states who came for a year or more to improve their Spanish communications skills. Other large cluster of students that were career and creative arts oriented included the artists (people called them “the painters and the potters”), archeologists, creative writers, journalists, historians, and social scientists, and finally those people who were training for business or foreign service careers in Latin America.

Finally, there were many American and some European students at MCC who were there primarily for the outside activities that were available to them within the rich and varied array of natural settings, and for the cultural diversity that existed in Mexico City and its hinterland. It seemed that we all felt the power of place in Mexico’s landscape and its people, and at the time it was a place where physical and human landscapes blended harmoniously together.

The largest subgroup among students who came to Mexico for opportunities outside the classroom centered on the MCC Explorer’s Club, but included many independent adventurers as well. Oriol Pi-Sunyer, a Spanish Civil War refugee via France, England, and Venezuela, captured a number of the elements that this group shared:

“It is possible that I learned as much outside academic contexts as in the classroom. Travel in Mexico was cheap, particularly for those ready to patronize country buses and third class carriages. Few of my friends owned cars, but we were certainly mobile, making numerous trips through much of central Mexico and beyond. We trekked mountain trails and went on indigenous pilgrimages, often following routes dating back to Aztec times. A good deal of this activity would now be classified as ‘adventure tourism,’ but it formed part of a venerable travel tradition premised on the assumption that knowledge of people and places was gained through personal experience.” (Pi-Sunyer, 2003, p. 27)

Also within this subgroup cluster of students who came primarily for the available outside activities were students who came to MCC to (a) to become the “new expatriates” by creating or finding a 1920s Hemingway-like Paris or Pamplona, (b) play team sports, (c) use the campus as a base for commuting back and forth to Acapulco as “surfers” and “beach bums,” and (d) to thrive in the active bar culture.

The latter group who came to engage with the bar culture included students who can be classified as “big city drinkers, brawlers, and thinkers.” These students were often older, experienced urbanites from Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Chicago, and other major cities where drinking was considered a major activity. Occasionally these students ended up in jail for a time, after getting into fights and conflicts. Pete Hamill (MCC, 1956-57) wrote about this drinking subculture during his year at the college in his book, A Drinking Life: A Memoir, (Little Brown: Boston & New York, 1994, pp. 189-208). Hamill captured the mood well (p. 194):

“There was drinking everywhere, and Tim and I were part of it. We went drinking in the small hut across the highway for the school, in the cantinas near where we lived, at weekend student parties all over the city. Those parties bound us together. In some ways, it was like the navy. Everyone was far from home, far from Ohio and Illinois, for states with age limits on drinking, far from inspection by friends or family, all using drink to deal with strangeness and shyness and a variety of fears. At MCC there were two American men for every American woman, and the sense of male contest gave the parties a tension that occasionally resembled hysteria. The rule was BYOB, bring your own bottle, and in the doors came cases of beer, bottles of tequila, mexcal, pulque, rum. These were 1950s parties, young men and women packing the chosen apartment, dancing, as said, teeth to teeth, to the music of Benny More and Los Panchos, drinking with little care about food, faces swirling, ashtrays overflowing with butts, hot eyes falling upon asses and tits, tits and asses, until the midnight hour had long passed, and finally the last of the women were gone, and the remnants of the bleary male squadron kept drinking on until the beer ran out and you could see the worm in the bottom of the mescal bottle and it was time to face the gray down. I was happier than I’d ever been.”

Obviously, Hamill and his friends found instant satisfaction. A number of other younger students took a little longer to adjust. Many of them started out by not liking the college, the city, or the people. Perhaps it was culture shock, or just an old-fashioned, national chauvinism that played out along the lines that “everything at home was better.” The “old timers”—anyone who had been there at least two quarters—knew what the litany of comments would be every quarter when a new wave of students arrived, especially the “Winter Quarter in Mexico” students from Ohio State and Michigan State. The old timers also knew that the new students’ negative feelings would virtually evaporate within a short period of time, and within a short ten week quarter they generally would become quite emotional over their pronouncements of affection for everything about Mexico, the culture and its people. Before leaving, the vast majority of students started working out a strategy for staying permanently in Mexico, although only a small number of them were able to accomplish it. What was common to nearly everyone was that they left Mexico reluctantly with thoughts or plans of returning as soon as possible. In my own case I left for the University of Washington in January 1959, but returned to Mexico City College while working on my Master’s degree in 1960-61.

Another interesting group centered on the expatriate hangers-on. This smaller group of students, often in the 40 to 60+ age range, were discussed previously, and included the “premature anti-fascists” who fought in the Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War, or were arm-chair philosophers who lived up the hill from the college in the small village of Cuajimalpa. Many were beyond taking courses, but they frequented the library and liked talking in the cafeteria to each other, to ex-GI veterans and to other students. Another group that lived up the hill in Cuajimalpa where they could dress like natives and have an authentic experience living in a Mexican village. A number of them thrived on drinking pulque, a fermented alcoholic drink from the maguay plant, which tended to keep people at a low-level of inebriation all day. These students attended some classes, and others spent time around the campus.

Finally it is important to mention the small group of “cold-war agents” that were pretending to be students. They enrolled as students at the college, but their actual purpose was quite transparent by the kinds of questions they asked to check out the social and political lives of students and international refugees. Students were not concerned that they were present on campus, since ever other type of student was there as well and these “Keystone Cops” added something to the unique mixture of ”ambiente” at the college.

.

Student Economics

The money factor accompanied us at all times, and it was a major reason why many American students came to Mexico. It was a simple fact that the American dollar went a very long way in Mexico—much farther than back home. A student in the States had to live very modestly, while American students in Mexico, under most circumstances, could have a far grander standard of living. Not only did the United States ranked first in the world in 1957 in per Capita income at $2,343 per person (see Ginsburg, Norton, Atlas of Economic Development, Univ.of Chicago Press, 1961, 18-19), it was 40 percent higher than second-ranked Canada with $1,667. Switzerland, the highest-ranking European country, was in fourth place at $1,229 per Capita—about half that of Americans. Averages for other major European countries included France with $1,046 (9th place), the United Kingdom with $998 (11th place), West Germany with $762 (15th place), and Italy with $442 (26th place). Mexico placed even much lower on the world economic scale in 57th place, with an average income in U.S. dollars of only $187 per person. That fact that the average Mexican earned only 8 percent of the average American at that time meant that American students could live at a far higher level than back in the States. Life in Mexico City clearly was more expensive than it was in the countryside, but it was still an overwhelming bargain. Tuition at MCC in 1955-56 was $105 per quarter, plus a medical fee of $10. Two years later (1957-58) tuition with medical included was up to only $130 per quarter. Since the ex-GIs received $115 a month on the GI-Bill during that period, it annually gave them $1,380.

Even then, surviving economically was an overriding topic that MCC students talked about much of the time. Veterans had to wait for the 15th of the month for their GI bill checks to arrive, and others of us had to constantly check the mail from home to know whether we would have to borrow money from friends or whether we would be the ones who could be tapped for a loan. There was an unwritten code about borrowing, repaying, borrowing again, and asking, “Who has the money this week?” There was a vast network of connections, the major requirement being that records needed to be maintained. The overwhelming majority of loans among MCC students were repaid, but there were a few students who thought it was okay to ask others for loans, but, if others asked them to repay the loans when they were broke, the response was, “Stop dunning me, I pay my bills!” Since they never volunteered to repay the loan, and then objected when needs were reversed, these people were soon cut out of the large “friendly aid” network that had been constructed among students who sometimes felt stranded with nowhere else to turn.

Working in Mexico on student visas or tourist visas was illegal, but there was an accepted gray area under which everybody operated. Students at the college often needed to supplement their finances. Several of us were paid between $50 and $60 a game to play American football for two Mexican universities. The league officials were seeking to expand the top league from four teams to six, so they hired a handful of imported players from Texas, as well as a few MCC students to strengthen the two new teams and to improve the quality of play in the league in general. Officially this was illegal, but it appeared to be out in the open. I played for the Mexican Military Academy—Academia Militarizada Mexico—with three other MCC students. The league also brought in an American coach from El Paso, Texas with eight West Texas players to add to our team, so considerable tension developed between the Mexican players and the Texans on the issue of who would start the games. The solution was to rotate the starting team from week to week. The four Mexico City College players were in the strange position of being wanted desperately by both teams, so I found myself starting at tackle after only five days of practice on the Mexican team in the first game before 80,000 fans, and then staying in to play for the American team when they entered the game. By the end of the game I could barely crawl off the field, exhausted as much by Mexico City’s 7,500 -foot altitude as by having played for two successive teams.

One area of employment that was never question centered on the fact that MCC students were frequently used in Mexican movies as bit players whenever gringo characters or villains were needed. In April of my freshmen year at MCC, I was picked to play the major villain—an American Olympic diver Gary Tobian—in the Mexican movie Paso a la Juventud, which centered on the Pan America/Olympic rivalry with Juaquin Capilla, the only Mexican gold medal winner in the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. In doing so, I missed a chance to be an extra with other MCC students who were extras in two American movies being filmed partially in Mexico at the same time—The Sun Also Rises, and Sierra Barron.

Other students found odd jobs when they could. One friend was hired by a hotel chain to test their security systems by entering the premises and stealing things. Several times he was nearly killed when caught, since the guards did not know ahead of time that the hotel had hired him. It finally became too dangerous, so he quit. In that case, personal survival took precedence over economic survival.

Excepts from the following letter (March 1960) from an unnamed graduate of Mexico City College (1959), best illustrate how some jobs played out:

“I left Mexico in September. Last year there I really had a good time. While finishing at the college, I lived with Freddie W. for awhile and then the police kicked me out of the apartment because of a wild party. I then moved in with some girl who left me (the bitch) in June with $8 in my pocket, and I wasn’t getting any money from my folks. So---I went to Acapulco and the “Snake Pit” and the old lady owner, who always kind of liked me informally, adopted me and gave me free room and board all summer. …. I was of course broke, so I got a job managing the nightclub in the Aloha Hotel, which was a ball. It was really going for a while, but then the tourist season ended and I went broke trying to keep the place going. When it was really strong, though, I had a seven-piece cha-cha band and floor show.

I went [back] to Mexico City then and ran into the girl who was entitled “Miss Universal Beatnik” and was in Life magazine because of it. She was down there with a bunch of beatnik friends and since none of them had a place to stay, I got a room in the Hotel Rey with her and her girl friends. This sounds like a good deal, but you ought to try and live with a bunch of beatniks. Man, in a little while they would have driven me crazy. Besides they were always taking dope and I was afraid the cops would raid us, so I moved out and came up to the states and here I am at present.”

[After realizing that his economic situation was in shambles, he joined the Army.] He went on to say: “When I got to Massachusetts I went down to New York City and Greenwich Village and ran into the same beatniks again, so I’m sharing an apartment with four girls now on weekends, including “Miss Universal Beatnik.” ……..

Well I sure wish I was back in Mexico. I hate this cold weather up here. I’m in the Army Security Agency, which is a pretty good deal as far as the Army goes. They are sending me to school for 6 months and then overseas to the Orient or Europe, which will be all right with me.”

Mexico City as Center of Foreign Intrigue

Since the 1930s and well into the 1960s, Mexico City had been a haven for international exiles, and many of them lived in the part of the city where many MCC students also lived in the 1950s and 60s—the districts of Cuauhtemoc, Juarez, Zona Rosa, Roma Norte, Nueva Anzures and Polanco. These exile groups included political refugees from Republican Spain after the Spanish Civil War, with estimates as high as 24,000 (Pi-Sunyer quoting Pla Brugat 1999: 161), including some Americans from the Abraham Lincoln Brigade that fought in Spain in 1937-38, and had been branded “premature anti-fascists” by the U.S. government.

At that time— in the 1950s and 60s—Mexico City was considered by many to be the “spy capital of the Cold War,” because it was where international espionage could flourish, with agents and informers being able to move through the city to be redirected in all of the cardinal directions—north into the U.S., east to Cuba and flights on to Eastern Europe, south into the rest of Latin America, and even west toward Asia through the less obvious backdoor via the Pacific. Berlin was a “listening post” during the Cold War, but Mexico City was a “movement center” for spying. The Russian Embassy in Mexico City was huge and active, and the U.S. presence of CIA agents and FBI agents (who were not supposed to operate outside of the U.S.) were all over the place, even at Mexico City College where they could check up on American expatriates and left-leaning students, but mostly they mixed in at the National University of Mexico (UNAM).

On the political left, also living in these same districts, were refugees from Latin American dictatorships like Batista’s Cuba and Somoza’s Nicaragua, dissidents such as the previously discussed Fidel Castro, Ché Guevara, and ex-Spanish Republicans such as General Alberto Bayo, who trained Castro’s men for the invasion of Cuba in the fall of 1956. Even Lee Harvey Oswald apparently spent time in Mexico City in mid-1963—although his presence is still debated—to connect with the Russian and Cuban Embassies seeking visas to pass through Cuba in an attempt to get back to the Soviet Union.

Mexico City as the Heart of the Country

Without a doubt, Mexico City was the most important place in Mexico for Americans during the 1950s. At that time few would contest that the heart of the nation was centered there. But where within the city was the heart? Responses to that question vary by perspective. In reality, four distinct centers for the nation exist within Mexico City—a political center, a cultural center, a center of nationalism, and a religious center. Americans came to these places frequently to enjoy celebrations and to share with Mexican people their appreciation for the country.

The “political” heart of Mexico has always centered on the Central Zócalo (Plaza de la Constitutión), which is the largest open plaza in the country. Facing the Zócalo on three sides are the National Palace, the Municipal Palace, the Supreme Court, the National Pawnshop and other government buildings. On the fourth side of the square is the Metropolitan Cathedral. The Zócalo is where major ceremonies, demonstrations, and other political events take place at various times throughout the year.

The “cultural heart” of Mexico in the 1950s centered around the Alameda plaza. The Alameda was bordered by Avenida Hidalgo on the north, the opera house “Bellas Artes” to the east, and along Avenida Juarez on the south were the National Museum of Popular Art, and the Hotel Del Prado, where covering the lobby walls of the Del Prado were many of the key murals of Diego Rivera and Miguel Covarrubias, until they were lost in the devastating earthquake of September 1985. The most important Diego Rivera Mural was later reconstructed and moved to a new location on the west end of Alameda plaza.

Mexico also had a heart for national independence, which is also tied to the “spirit of the Revolution of 1910” by many as almost a second independence, and that place was located on the glorieta where the tall majestic Monument to the Independence stands. “El Angel,” as it is called, is located where Paseo de la Reforma meets avenues Río Tiber and Florencia in the Pink Zone. A rival for this honor of national independence was the big bulky Monument to the Revolution on Avenida de la Republica, but that oversized square does not have the magnetic pull or strategic location within the city that the Angel possesses.

Finally, the “religious heart” of Mexico for many of the common people, was located at the Villa de Guadalupe, where the Virgin of Guadalupe first appeared in 1531, and its old Basilica near Avenida Insurgentes Norte. Every year on December 12th, tens of thousands of pilgrims came from every corner of the country to sing a birthday song (las mañanitas) to the Virgin. Americans too were attracted there throughout the year.

Other Special Places for Americans in Southern Mexico

Americans in Mexico in the 1950s were attracted to a number of places in the greater hinterland around Mexico City and the southern part of Mexico. Greater Mexico City, with fewer than three million people in 1950, was the most important place for Americans in the country, and the U.S. students at Mexico City College added significantly to the numbers of Americans living there. While on weekends certain smaller villages and towns near Mexico City drew some Americans who worked or lived in Mexico, most of the countryside was nearly exclusively Mexican. Other favorite places places for Americans were Cuernavaca, Taxco, and Acapulco to the south, Puebla and Oaxaca to the east and southeast, and to the west in the state of Mexico beyond Toluca was the newly developing resort area at Valle de Bravo, as well as the mineral baths at Ixtapan de la Sal. Other mineral baths at San José Purua in the state of Michoacán, where the Spanish film director Luis Bruñuel lived throughout the 1940s and 50s, also attracted Americans, as did the old colonial city of Morelia and the villages around Lake Patzcuaro. Farther to the west, favorite places for Americans were found in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, and Guadalajara, as well as the north side of Lake Chapala in Jalisco state. The beach resort centers of Puerto Vallarta and Mazatlán were still in their infancy, but they represented the beach resort options in that part of Mexico. Beach options on the Caribbean side of Mexico centered on the city of Veracruz, but because of the arduous trip from Mexico City, many travelers often stopped over at the spas of Fortín de las Flores under the eastern flank of Mexico’s highest volcano, Orizaba, and close to Córdoba, Veracruz.

At that time, no highway existed along the Pacific Ocean between the state of Colima and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in eastern Oaxaca, and no major highway connected directly between Mexico and Guatemala. The Yucatan Peninsula was virtually an island connected only by one rail line via the state of Tabasco and boat traffic, mostly from Veracruz. The first major road connecting the Yucatan with the rest of the nation was not opened until late in 1960, and even then more than half a dozen ferry crossings had to be used, including those connecting along the Caribbean coast via Isla del Carmen. Thus, options for Americans for comfortable leisure time in favorite places were far more limited in the 1950s than at present.

The Drive to Acapulco

Driving on the rural highways and back roads of Mexico was something like playing Russian roulette—especially at night. Most of our drives back and forth to Acapulco were on a Friday night after classes, or returning on Sunday night after taking advantage of the beaches all day. The drive each way was at least six hours, and sometimes more depending on what tragic event we would come upon. On those trips the driver had to be scanning the road ahead with total intensity, often aided by a co-road spotter in the seat to his right. Things popped up in the headlights out of nowhere very quickly—usually cattle or other animals—but sometimes a bad wreck or a dead person in the road—and when suddenly the car passed these events and it was difficult to look back. All the advice was never to stop, or you will assume responsibility for what happened. As the night progressed, especially on weekends or moonless nights, it was very difficult to spot men who had passed out from overdrinking crumpled along the side of the highway or sometimes in it. We never hit anyone, but we came close a few times, and we seldom made the trip at night without seeing a dead man on the road.

Several memories are etched in my mind. One evening on the way to Acapulco about 11 pm at night, a much faster car tore past us on a straight section of the highway at a speed that must have been in excess of 80 mph. As the car reached went beyond the reach of our headlights, its red tail lights all of a sudden shot straight into air for 10 or 15 feet, before falling back to the highway just as our headlights could see the shattered car bouncing around on its tires. We slowed and pulled up to a smoking, steaming late-model car with one passenger through the windshield, and with bits of metal, glass and animal parts all over the highway. It turned out that the car had hit the back end of a nearly 1000 pound bull dead center, directly between its headlights. The sizzling engine had been pushed into the open seat space between the driver and the passenger, and somehow both of them were still alive. The only thing that saved them was that they hit the bull directly in the center of the car, rather than with a glancing blow that would have thrown the car rolling and flipping down the highway.

That same evening south of Chilpancingo, about two hours later, we arrived where a second-class bus with passengers had gone off the highway and down a hillside of thorn trees into the canyon bordering Río Omitlán. Here we ignored the advice not to get involved, and we worked well into the night helping several dozen volunteers form a human chain down the hill where badly injured survivors were lifted and passed back up to the roadside.

Breaks in Acapulco

Acapulco at the time was the favorite Mexican coastal vacation spot for nearly everyone at MCC, especially during the breaks between quarters. Acapulco was a more relaxed break from classes, and from long weekend explorations to more remote places in the interior of the country. Acapulco was so strongly Mexican that it now stands in sharp contrast to the new super-resorts that are carbon copies of one another. They are often set in unique and interesting places, but they would have held little appeal to most MCC students. Why come to Mexico to find an artificial enclave created for the rich and not so beautiful, or to find a place that is nearly a carbon copy of the place one had visited the previous month? Give me a place like Acapulco, set in a Mexican city, where Mexican tourists and families have vacationed since before the 1920s. Acapulco in the 1950s was an ideal place for our vagabond group of poor students. On the main beaches of the harbor there were no “super-sized” hotels, or hardly any hotels of any size. Across the palm-lined boulevard Avenida Costanera Miguel Aleman, named after the ex-President from 1946 to 1952, that bordered the long harbor, there were some low-rise hotels, but for the most part, views from the Avenida of the main beaches remained sweeping and unhindered. Locals and visiting Mexicans used the beaches for soccer games, sunning, swimming, and fishing. In the late afternoons, chefs and housewives waited where crews of eight or ten oarsmen rowed medium-sized boats up to the beach. Behind the boats trailed long nets teeming with live red snappers and other fish. Once the boats reached the beach, the rowers jumped into the surf to begin pulling in the nets full of fish. After some heated bargaining for the results, the chefs carried their newly purchased fish directly to the open-aired restaurants throughout the downtown and along the costanera, while the housewives shuffled toward home carrying straw baskets with the fish half hanging out.

The peninsula and areas around Caleta Beach and Caletilla Beach had one grand hotel—the Hotel Caleta that perched on the point above the beach. A little farther up the hill to the west was the famous Hotel Flamingo that John Wayne had owned since 1950, and where he hosted his Hollywood friends, including Johnnie Weismuller (Tarzan) who lived there huntil he died in the l980s. Our band of poor college students and ex-G.I.s, however, never frequented either of those places, but hung out around the other low-rise and small hotel pools or beaches that were easily accessible. Our favorite place to stay was the Hotel del Pacifico at the far end of Caleta Beach. The hotel was shaped something like a battleship, but with a large covered, open-aired restaurant on the second floor. We stayed there for only a few dollars a day.

Most of the hotel managers seemed to like the presence of gringo students, so we had the run of virtually every place in Acapulco. They seemed pleased when our group arrived to use their swimming pools, bars, restaurants, bathrooms or lobbies. It was especially true when members of our group brought guitars for impromptu parties after the “cuba libres” or local beers as the sun set and the hotel guests returned from the beaches. All the small places wanted to create a certain “ambiente” for their clients, and for some reason a rough and tumble group of relatively benign gringos seemed to please nearly everyone. If the party got too lively for the hosts, as it sometimes did, we just moved to the next hotel, or perhaps back to the “Bum-Bum Club on Caleta Beach, or even to someone’s suite for a jam-session of raunchy and rowdy songs.

During spring break of my freshman year, late March 1957, six of us drove to Acapulco for a 10-day vacation away from our studies—my brother Jim, Ted Turner (a GI veteran from Nashville), Murray Pilkington (a southern Californian), Elvis look-alike Mike Johnson (a northern Californian) and the friend with a car—an ex-GI named Gil from New York City. The second night in town, we ran into a weird and wonderful social group that drew us into their parties and scene for the rest of our stay. One of the leaders of the group was Lady Sanchez, an older woman who had spent so much time in the sun her skin had the texture of a brown leather mummy. She claimed to be the daughter of the Duke of Buckinghamshire (England), and that her first husband had been Rex Harrison, the actor. Another leader was Tony Clark, who wrote The Hucksteers, which later became a movie. Tony, who was also English, was in Mexico writing an article for a magazine. Since he was on an expense account, he kept the glasses full of rum and the grilled huachinango (red snapper), cerviche (raw fish in lime juice), and fresh shrimp on the plates at every restaurant and nightclub we spent time. As poor struggling students we were certain that we had arrived in paradise.

Members of the Lady Sanchez/Tony Clark group included Lucy, a lovely ballet dancer from New York City who kept Tony company, Pearl, a music teacher from St. Louis, a secretary from Oakland named Marge (one of the most beautiful women in Acapulco), and Peter, a book publisher from New York. Other college friends joined us from time to time including ex-veterans, Sherm (from California) who disappeared frequently for an affair with a married woman, “Phantom” (an Alaskan fisherman) who was staying with his highly pregnant Mexican girlfriend, and Bill (from Houston) who managed to get in a big fight with some prostitutes at one of the sidewalk restaurants on the central zocalo where we were spending the evening, and the police were called in end the fracas. Others individuals were involved as well during this stay, but this group made up the core of the revolving whirlwind of letting off steam from our studies back at Mexico City College.

By the end of the week, Tony Clark asked six of our MCC group to accompany him as “armed guards” on a 10-day pack trip into the mountains of Guerrero in search of material for his article. Reluctantly we had to return to classes; we never heard whether he took the trip on not, or whether his article was ever published.

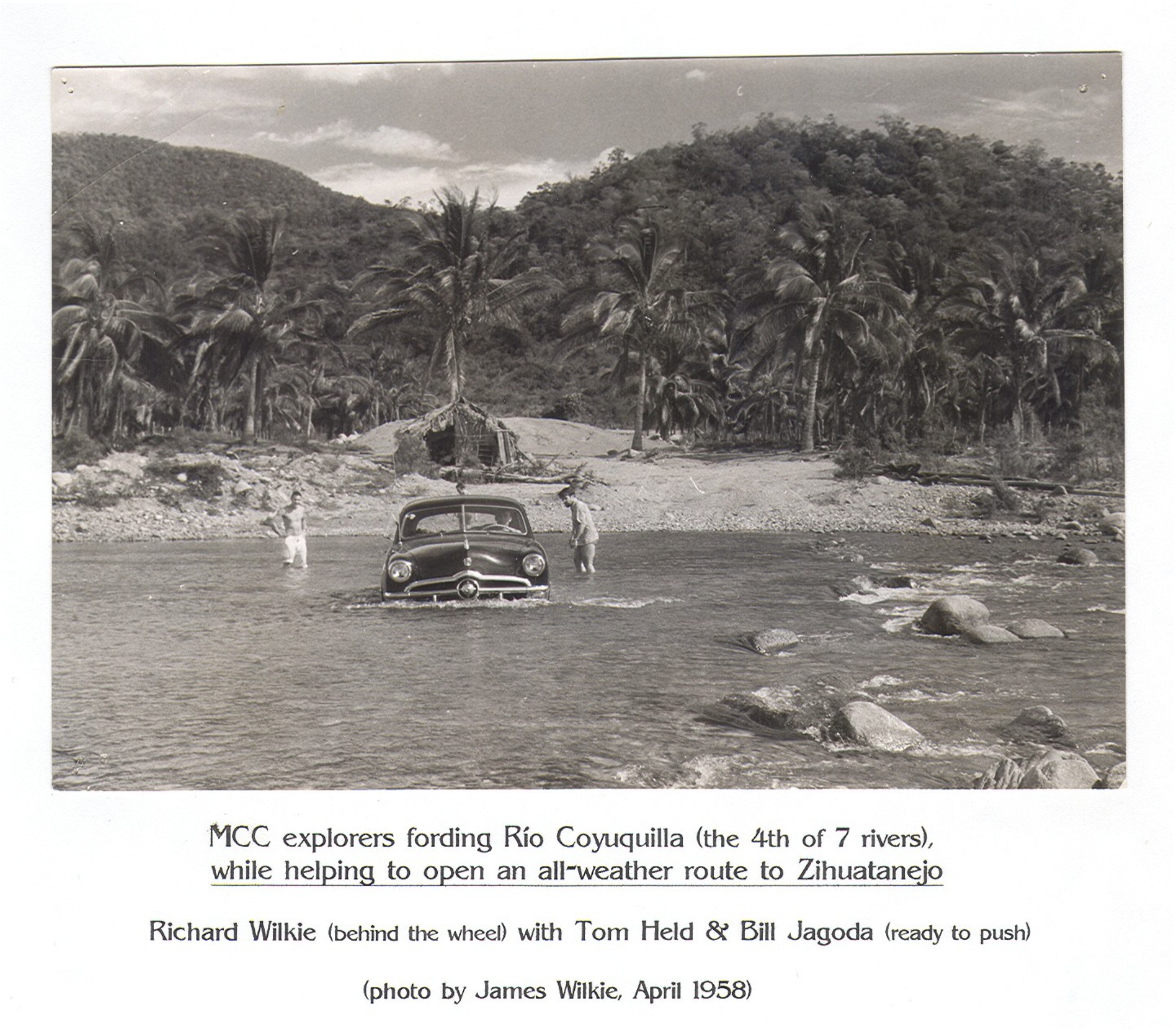

Driving to Zijuatenejo

Most of our school breaks were not spent leisurely in Acapulco, but were spent more productively hiking or traveling to out-of-the-way places. During spring break in March 1958, after reading that a new “all weather” road had finally been opened to Zijuatenejo, six of us made that our primary destination. We did spend a few nights in Acapulco coming and going each way, since the 140-mile road up the coast departed and returned there. The news article alerting us to the trip said “depending on the season, the trip could be made in 10 hours to two days.” During the rainy season from May to October or November the rivers were extremely high and difficult to ford, especially the Río Coyuquilla, Río Petatlán, and Río de las Cuevas, and “you can count on spending at least a day stuck in at least one river.” Fortunately we were still in the so-called dry season when passage was not easy, but possible if a driver had help to ford rivers.

On our trip we discovered the “new road” petered out into narrow dusty trails after crossing the Coyuquilla River about 50 miles short of our destination. Those final miles involved pushing through another four rivers with water well up into the car and all hands pushing. Between those crossing we struggled not to lose our way among the jungle cattle-trails or the footpaths leading out of small villages along the way. One thing was evident—the people were the friendliest we had seen in Mexico. They waved, shouted and helped us on our way, marveling at the 1950 Ford we were driving as a “coche nuevo.”

In an article my brother Jim wrote for the Mexico City College Collegian (May 15, 1958): “Intrepid Gringos Discover Poor Man’s Acapulco,” he noted that:

“Zihuatanejo may be the place Zane Grey emphatically declared more like the South Seas than the South Seas themselves, and again it may be the “coming” tourist resort on the Pacific coast, but both statements may stretch their points. Zihuatanejo is typical of Mexico’s West coast, according to Mike Johnson, and not so typical of the South Seas. It will be several long years before Zihuatanejo reaches the level of even Mazatlan’s cleanliness and modernness, let along Acapulco’s fame.”

The first place we encountered in town was a police checkpoint, and they were so surprised at out arrival, we had to wait nearly half an hour while they found the chief of police. He was very welcoming, but said that he was concerned for our safety and that he was assigning an armed policeman to accompany us. “Remember, this is Saturday night, and all the machete swinging men come into town to get drunk and rowdy. Why pick a fight with a man who also has a machete, when you can fight with foreign gringos?”

Having a guard with us was not a bad idea, especially after seeing the characters drinking at the major bar in town. Even the building housing the bar was disreputable, with a dirt floor, tree branches for walls, and wooden beams above our heads holding up a flimsy roof. This was like “the wild west” from 1920s American cowboy picture shows.

We had one thing going strongly in our favor while we were in this bar. John Freeman played his rock and roll guitar for the crowd, while several of us sang off colored blues and rock songs. None of them understood our Spanish, and we were not sure which of the many Indian dialects they were speaking. One man among the rural woodcutters stood out well above the others in his size and ferocious appearance. He appeared to be over six and half feet tall, and in facial features had a Boris Karloff look about him. I was so awe struck that I don’t remember taking my eyes off him the entire evening. To make matters potentially more ominous, it appeared that our friend did not speak a word of Spanish, or perhaps any language, but used instead strong guttural sounds when attempting to communicate. The other woodcutters seemed to defer to him and keep out of his way, so for most of the evening he moved in to join us at our table. He clearly liked the music, as he laughed frequently and showed his approval by heartily downing Carta Blanca beers we kept pouring for him. I will always remember that his hands were so big that when he clutched the beer glass, he appeared to be drinking from his giant fist. In all my time in Mexico I never saw a more colorful or fascinating fellow.

The beach near the two-street village was not a good place for swimming, so we hired a boat to go to the other side of the bay to perhaps the most beautiful beach we had seen in Mexico—Las Gatas (she-cats). It was there that lush jungle foliage swept down to meet white sands, which bordered the softly tinted green waters of a sheltered nook on the bay side of the palm-tree covered shoal that arched out from the shore. Ocean waves crashed 100 yards off the point over a coral reef that protected this magic location. Not all adventures ended on such a high note, in such a dramatic setting, but hopefully somewhere Mike Johnson, Tom Held, Bill Jagoda and John Freeman still remember the feeling of discovery that we all felt at the time.

Unfortunately, even paradise has problems, and before leaving the beach that afternoon, while looking for colored blowfish, John Freeman stepped on an underwater spine plant. Half dozen quills pierced the skin in the soft bottom of one foot, and their toxic poison caused a fever for a day and real discomfort for a week or more. Removing the quills took the expertise of an old Indian couple living near the beach on a site that is now probably covered by a giant beach hotel. Having never returned to Zihuatanejo, I have the luxury of dreaming that dramatic changes have not taken place there and that the beach at “Las Gatas” remains as it was in 1958.

Mexico: Learning to See Details

Experiencing the Mexican landscape in those years helped me to see more clearly the everyday world, something that life back home with its tranquility and blandness would not have provided. Vistas in Mexico were so full of rich details of color, patterns, and variety in the natural and built environments that I realized even more strongly the importance of seeing things at three different scales—overview or wide-angle perspective, medium-scale observations of one’s immediate surroundings, and the more focused examination of up-close details in what can be called “still-life scenes.” This helped me to gain a taste for wanting to understand complexity and diversity in my surroundings—something that helped me begin to understand life more completely in Mexico—and what seemed chaotic to some became commonplace to me and other MCC students.

Reading the landscape and to grasping what I was seeing was something I had learned to do instinctively in a wilderness upbringing in the Salmon River country of central Idaho. I learned, as did my brother Jim, that survival could depend on remembering details in the landscape and how they varied at different times of the day. We had to construct very accurate mental maps if we were to find our way back or find the safest and best route up or down a mountain face. Art classes also had been an important setting for learning to focus on details. Now, in Mexico, it was possible to hone those skills as the landscapes and human activity spaces came together in a honeycomb of action and excitement as places in ways that far exceeded anything at home in the states.

Take, for example, a periodic Mexican market, where a multitude of visually exciting elements is jammed into a handful of blocks. The density of the mix is as though people and their activities had been thrown into a bowl and stirred with a giant wooden spoon. Add the sounds, smells, and tastes of the market and for many it can be a nearly overwhelming experience.

The Toluca Market on Fridays, for example, was so rich in actions, sights, sounds, and smells flooding one’s senses that most non-Mexicans reacted in one of two ways. Either they jumped into the scene and reveled in it, or they looked around for a bit before fleeing to a bar or café where it was possible to focus one’s senses to a less dizzying array of action. I often had another strategy that helped give me a feeling of structure to the apparent chaos and disorder. I first looked for a high place to capture an overview of the basic layout of the market, and where best to gain a perspective of the activities that were clustered in each part of the market. Gaining a feeling for the whole gave me a solid understanding of the parts, and even which places appeared to be most appealing to visit early and which were just beginning to evolve. Every market has a rhythm, and it is imperative to feel that ebb and flow of events and activities. Arriving at the crack of dawn along with the vendors is the best time to get in sync with that rhythm, but that is not always possible. From above one can feel the pulse of a market in the myriad of sights below and discern which parts are building toward some kind of a crescendo. Some people shy away from climactic events, but I am drawn toward them. Thus the overview perspective is a time to get in touch with these feelings and to begin a flexible plan of action.

After coming down from the overview perch, it is time to explore the intermediate-scale perspectives within the market area. This is a phase of observation and exploration where it is important to screen out the chaos and look much more closely at clusters of activities. The action of one or two venders and their array of colorful produce or handicraft; the people who bargain or talk with them; the young child pulling on mother’s dress or father’s pant leg to get attention as the parent is handing change to a customer; the dogs under foot that are searching for and finding scraps—all of these events and more are taking place in small micro settings, of which there are thousands of versions occurring simultaneously in big weekly Mexican markets. Exploring them, framing them in the minds eye—even sketching them or photographing them—is all part of experiencing the intermediate scale. During this phase I generally spend time in every section of the market, pausing at times near central points—perhaps near a fountain or smaller mini-plaza, where one can sit for a while and people watch. The endless array of human characters of all ages and backgrounds, as well as animals, can keep the observer entertained for long periods of time. Where else other than in periodic markets do the worlds of rural peasants and urban dwellers come together so completely?

Finally, there is a scale that is often overlooked by market goers and travelers—the perspective of close-up details. For a final trip through the market, walk slowly as you try screening out the jumble of organized chaos, just thinking and framing one’s vision into small detailed spaces. Perhaps it is noticing the wrinkles on the back of an old vendor’s hand; spotting a military medal on the lapel of someone’s jacket; appreciating aesthetically the light angles and shadows on a small pile of yellow lemons or on the rounded shapes of small bread rolls; catching visually the meeting of two hands as money is exchanged between vendor and buyer; or spotting such things as the sparkling gold tooth of the flower lady or the textured look of a well used sombrero. Details in the built environment are just as important, such as an old manhole cover in a cobblestone street or the grillwork over a window that opens to the market. These visual treats are like a dessert at the end of the day.

Memories of these markets touched my soul in ways that make them live on. Clearly they are vital elements in my search to capture a “sense or spirit of place” in Mexico, and those places not only include the natural and build environments, by the human activity spaces that involve people of all ages, all socio-economic levels, and all rural-urban backgrounds. It was understanding something about that combination that helped me appreciate the complexity of Mexican diversity.

Conclusion

Mexico City College was an important institution of learning for American students who wanted to experience life outside the United States during an important period in the 1950s and early 60s, when those kinds of educational experiences were not freely available elsewhere. On a personal level, where else but Mexico could a college student directly out of high school in the States have the range of experiences that I had at that time? During only my first year and a half in Mexico I climbed peaks higher than anything in the 48 contiguous States (18,887 and 14,969 feet), played an American Olympic diver in a Mexican movie, played football games before crowds of 80,000 to 100,000, explored much of southern Mexico and Central America—often pushing our car through rivers or with it on the flatcar of a train—listened to countless stories of the adventures of ex-G Is who had fought in Europe and Asia in WWII and the Korean War, and experienced the everyday life and intrigues of Mexico City. To say the least, life there was in sharp contrast with everything at home in the States.

On a broader level, the college provided a dynamic setting for intellectual and personal growth, and it was a place of unimaginable opportunities for exploration, discovery, adventure, and creativity. The intellectual, artistic and emotional pull of Mexico was strongly felt and the years each of us spent there changed us for the better. Following the McCarthy era at home during the early 1950s, the image of a colder, sterner “Uncle Sam” contrasted sharply with the image of a warm and nurturing “Mother Mexico.” And for those who gave Mexico a little time, the pull of mother Mexico will be with us for a lifetime.