Mexico and the World

Vol. 11, No 1 (Summer 2006)

http://profmex.org/mexicoandtheworld/volume11/1winter06/introduc.html

INTRODUCTION

James W Wilkie

Because of the deep and diverse economic and social interactions, the 1,951 -mile border that divides the United States of America from the Estados Unidos Mexicanos is one of the most dynamic economic and social regions in the world. This book examines major aspects of this cross-border dynamism by focusing on complementarities and interdependencies that especially stem from and/ or influence the Mexican side of the economic equation.

In presenting the findings of leading Mexican scholars organized by Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC), this book offers analyses that delve deeply into the general framework for U.S.-Mexico economic relations and helps us to fathom how each side of the US.-Mexico border makes its own contributions to the region's dynamism. Further, it offers case studies on key aspects of the development process and its cross-border complexities.

Context of this Volume

Mexico and the United States each contribute greatly in the flows of cross-border interactions. US. offers knowledge-based discovery and implementation of new technologies, which are facilitated through US. venture capital and third-country investment in Mexico, which in turn offers geographic proximity to the U.S. market. Where Mexico was once known mainly as a source of high-value labor at low cost for the assembly of such items as television sets and toys, it is now increasingly recognized for its abundance of labor with high-value/ moderate-cost managerial and technical skills for the manufacture such items as sophisticated medical devices that have been approved by the US. Food and Drug Administration for implant in US. patients.1

Author´s note: All amounts are in U.S. dollars.

Dynamism at the U.S.-Mexican border is enhanced by the constant and frequent crossing of people from north to south and south to north. For example, Mexican CPAs and engineers are increasingly commuting from Tijuana to Southern California, their border-crossing cards permitting them to help alleviate the shortage of highly qualified bilingual persons in the US. Each year, more than 600,000 persons cross from Southern California into northern Baja California to obtain affordable state-of-the-art medical and dental services.

With health insurance coverage for treatment in Tijuana and Mexicali becoming increasingly available for US. individuals and families, the US. is outsourcing medical treatment to reduce user costs. Health Net, California's third-largest for-profit HMO, which is based in Woodland Hills, offers a high level of care by encouraging its insureds to seek treatment through Sistemas Medicos Nacionales, the only Mexican health service provider licensed by the State of California. The providers have collaborated in employer-sponsored plans offered by Health Net for the past five years and have recently moved to offer coverage for an estimated two million uninsured persons without insurance who live in Los Angeles, Ventura, and Orange counties and/or in Tijuana, Mexicali, Tecate, and Rosarito. Under Mexi-Plan, the least expensive of the available plans, a person age 19 to 39 pays $75 a month and families pay $300 for HMO coverage.2

Cost to members is much, much lower for service in Mexico than in the United States. Health Net members make a $5 co-pay for office visits in Mexico ($15 in Southern California through the Salud HMO network). The plan offers 90 percent coverage with no deductible for hospital stays in Mexico (75 percent for stays in hospitals in Southern California with a $2,500 deductible and a maximum annual out-of-pocket cost to the member of $5,000).3 PPO plans are also available. There is no requirement in Mexico for HMO members to select the "primary care" physician, which can make specialized care difficult to obtain.

Cross-border interactions involve many factors, including

• Work, tourism, purchase of consumer goods and services, as well as family fiestas that unite cross-border families.

• Long-term lease of beach-front properties and construction of homes and condos by California residents who, in 2006, can buy for less than $300,000 (and often much less) a home that in Southern California might cost $1 million or more.4 (Non-Mexicans can buy structures but cannot own land within 60 miles of the border or within 30 miles of the coast-they can, however, effectively lease land for up to 100 years.)

• Manufacturing in Mexico's export-oriented manufacturing and agricultural industries.

• Redevelopment and expansion of the "Port of Ensenada Complex" by constructing at "Colonet Bay" (in Spanish, "Bahia Colnett," 80 miles to the South of Ensenada)5 the new Port of Colonet, its own city, and the railroad link to the United States-all where no infrastructure exists. Port Colonet will occupy nearly 7,000 acres (97 percent of it water and 3 percent tidelands). Bidding terms may call for the best proposal for handling one million TEUs (20-foot containers or equivalent units) during its first phase, expected to start by 2008 and take four years. Once in operation, it would come under the jurisdiction of the Port of Ensenada in 2012. Port Colonet may be scheduled to expand by 2025 to as many as six million TEUs. It is planned to handle only container ships.6 Container traffic currently handled at the mixed use Port of Ensenada will be shifted to Colonet by 2017 when the current operator's concession ends. Other types of cargo will be moved to the Port at El Sauzal north of Ensenada, leaving Ensenada to handle cruise ship and tourist activities.

• The building of Colonet Harbor will lead to the fourth major port in what 1 denominate as the "Greater Los Angeles-Tijuana Region."This region, which ranges from Ensenada in the south, to Ventura in the north and Riverside and Mexicali in the east, is destined to become the only world region with four major ports (Los Angeles, Long Beach, San Diego, and the "Ensenada Port Complex.")7

Although crossings are complicated by the smuggling of people, money, and narcotics, the challenges faced in managing them have required ever greater government financial resources on infrastructure and services in this international region.

Development of the Mexican side is based upon the influx of significant amounts of capital that seeks to take advantage of Mexico's fiscal incentives, low labor costs, and inexpensive transportation outlays to reach U.S. markets. Non-Mexican manufacturing corporations have seen the possibility of using Mexico's border to develop the labor-intensive stages of their production processes. Thus, investors from the U.S. and other countries have established in-bond plants in Mexico to receive such inputs as component parts that are produced around the world and imported duty-free via California to Mexico. Once in Mexico, the inputs are assembled into finished products for export-mainly to the US. but increasingly to other countries with which Mexico has Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). Mexico is the world leader in signing FTAs and the only country that has agreements with the European Union (EU) and Japan, as well as with the US., Canada, Bolivia, Chile, Uruguay, Colombia, Venezuela, Israel, and the European Free Trade Area. It is also now developing a special investment relationship with China.

The plants that use imported and now increasingly Mexican domestic inputs to assemble finished goods are called maquiladoras, a term that dates back to the mills that processed the grain for individual farmers in colonial times. The term maquiladora, used interchangeably with the word maquila, worldwide has come to mean foreign-operated plants that assemble products for sale in other countries as well as in the country where the plants are located. Increasingly, maquilas in Mexico are manufacturing-rather than assembling from inputs-whole final products. For example, Toyota Motor Corporation (of Japan, Mexico, and the US.) has shifted from assembling pickup trucks in its Tijuana factories to manufacturing the complete vehicle.

Traditionally, the maquila industry has paid taxes on the value added by the assembly process (mainly labor costs). Once the inputs are transformed into outputs, the product was exported to the parent corporation in the US. or other part of the world. The arrival of new, high-technology US. and Asian investment has revitalized the dynamics of the border economy. Mexico's maquiladora industry experienced a turnaround in 2004, as employment, according to the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, increased for the first time since 2000. Maquiladora employment rose 7.1 percent in 2004, following declines in 2001, 2002 and 2003 of 18.3 percent, 0-4 percent and 1.7 percent, respectively.8 In 2004, most major maquiladora industrial sectors experienced job gains. Some of the fastest-growing sectors included services (27.6 percent), chemicals (27.5 percent), machinery (17.5 percent) and furniture (5.5 percent). The three largest sectors in terms of employment share-electronics, transportation and textiles, which make up 71 percent of total maquiladora employment-registered moderate job growth of 5.3, 4.7, and 3.2 percent, respectively. Data for 2005 are even more encouraging, with the Baja side of the international border creating I 1.8 percent of Mexico's new employment and the area's GDP growing at 5 percent (7.5 percent in Rosarito) compared to Mexico's 3 percent national growth rate. The investment rate is dominated by foreign companies, whose direct investment constituted 58 percent of all new funds. Also by 2005, the UABC topped the list of Mexico's leading public universities. It has 49 degree programs rated as "high quality" by Mexico's accrediting agency and 96 percent of its students are enrolled in those programs. (Highly rated Monterrey Tec has 28 percent of its students enrolled in high-quality degree programs.)

As U.S. and other companies around the world seek to penetrate the U.S. market, which is the largest in the world, they seek to do so by economizing on transportation and labor costs, especially in manufacture of television sets and computers. During the 1980s, for instance, the state of Baja California became a large producer and exporter of electronic and electric appliances, developing into the largest producer of television sets by Japanese firms. Indeed, factories on the Tijuana border assemble and distribute more television sets than any other place on the globe and have since 2000 shifted to manufacture sophisticated flat-screen televisions based on digital technology, thus requiring high-end labor.

The dynamic U.S.-Mexico border region had made significant gains before the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect on January I, 1994. Since then, gains have doubled and tripled as they link economically the U.S. (and to a lesser extent Canada) to Mexico. The trade agreement has increased the extent and intensity of links in the U.S.-Mexico border region not only by attracting more maquiladoras and fostering trade but also by requiring greater technological investment in the plants and work force.

Ten years after NAFTA's inception, it is now clear that the context of the border is changing to present a new bilateral agenda that incorporates such issues as migration, social security, personal income taxes, and environment. Although the benefits of NAFTA are often denigrated by vocal minorities in Mexico and the U.S., the positive benefits are generally acknowledged. Nevertheless, the depth and range of NAFTA's impact on the border region is not completely clear-hence, the need for this volume.

Because many observers question the extent to which NAFTA should be expanded to cover a more extensive variety of affairs, few believe that NAFTA can foster the socioeconomic convergence of the U.S. and Mexico in the style of the EU. The EU specifically includes labor mobility and freedom of travel, while NAFTA specifically excludes those, even as fast-track globalization gains ever more momentum.

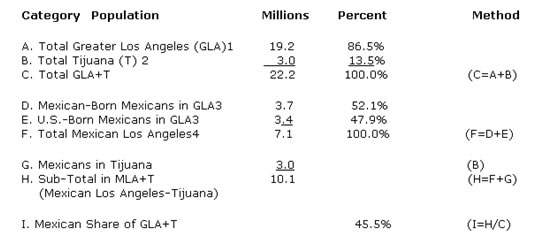

Table 1

Revised View of Wilkie's Concept of

Greater Los Angeles (GLA) - Tijuana (T)

To Include San Diego

Total Population in the Year 2000

and

the Sub-Total for Mexican Population in the Virtual Region

Mexican Los Angeles - Tijuana (MLA+T)

_____

1. Includes the following counties: Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura. Although Wilkie excludes San Diego County, I include it here. Data are adapted from Los Angeles Economic Development Corporation--see: http://www.laedc.org/stat_popul.html

2. Greater Tijuana here includes the Baja Border Region of Mexicali, Tecate, San Felipe, Ensenada, and Colonet.

3. See Parts 1 and 4 of text.

4. The term "Mexican" includes persons whose mother language is Spanish (such as Mexican Americans), Chicanos, Latinos, Hispanics) who identify with Mexican culture, without regard to lingusitic ability.) See text.

Source: James W. Wilkie, “Sobre el Estudio de Ciudades y Regiones: Reales y Virtuales,” p. 557 en ames W. Wilkie y

Clint E. Smith, eds., Integrating Cities and Regions: North America Faces Globalization

(Guadalajara y Los Ángeles: University of Guadalajara, CILACE, UCLA Program on México, 1998),

pp. 545-566. Ver también este artículo en la Revista Internet México and the World, Vol 2, Número 4 (1997). http://www.profmex.org/mexicoandtheworld/volume2/4summer97/afterword.html

The Greater Los Angeles- Tijuana Global City Region

Perhaps the full context into which this book fits can best be seen is in Table I. I, which shows Olga Magdalena Lazín's revision of my estimate for the population of the Greater Los Angeles- Tijuana Regional City in 2000. This region includes Ventura, Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, Orange, and San Diego counties in the U.S. and Mexicali and Ensenada in Mexico. The entire region has over 21 million persons, with more than 3 million located south of the border.

Table 1. I also suggests that the number of "Mexicans" in Greater Los Angeles as being 7. I million, the term Mexicans having come to include persons whose mother language is Spanish (such as Mexican Americans, Chicanos, Latinos, and Hispanics) and who identify with Mexican culture, without regard to linguistic ability. Also, here it includes Central Americans who have come to identify themselves as Mexican in order to gain protection of the larger population, all of whom make use of the Mexican Consulate. Certainly, then, the extent of Mexican Los Angeles is greater than generally understood. This population is also in constant flow within the region, regardless of the international border line, which only slows the movement of persons.

Organization of this Book

In Chapter I, Sarah Martínez Pellégrini suggests that NAFTA can encourage even greater development than it does for mutually beneficial economic and social regional policies oriented to improve the general welfare of the border zone. She analyzes the strategies for optimal local productive systems to build the critical mass needed for sustainable development. Martinez argues that a bilateral approach to environmental issues is a good starting point in developing "International Agreements and Regional Policies at the United States-Mexico Border," because it organizes information and data on managing common cross-border problems. Martínez, an economist at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte de Mexico, is affiliated with UABC for this research project in which she considers the actors involved in the regional development process.

In Chapter 2, Noé Arón Fuentes and César Mario Fuentes evaluate which regions of Mexico have gained the greater advantage from NAFTA. "Regional Economic Growth in Mexico: An Analysis of Total Factor Productivity" challenges the belief that the northern states of Mexico have increased their productivity and well-being and their economies have became more productive, while the southern states are in limbo. To test this hypothesis, Fuentes and Fuentes examine two conflicting approaches to measurement of change. The first suggests that the northern states have suffered a productivity contraction and that their growth has been driven by capital and employment growth rather than by positive productivity shocks. Such an approach suggests that the largest cities of Mexico have experienced incremental increases in their productivity. The second approach supports the hypothesis that northern Mexico in fact has increased productivity because of outward-oriented policies and the type of firms attracted. Thus, Fuentes and Fuentes show that the manufacturing output has increased for all regions but at different rates and that the higher growth rates are located in the northern states as well as in the largest cities, while the lower rates occur in the central region.

Chapter 3. "The lmpact of Economies of Agglomeration, Clusters, and Networking on Medium-Sized Mexican Telecommunication Firms,” by Alejandro Díaz-Bautista, addresses how national firms, especially those located in the border zone, successfully face the challenges of economic integration. In analyzing the advantages arising from the territorial clustering of related firms, Diaz-Bautista suggests that such territorial proximity generates scale economies by economizing the costs of transportation, information, and infrastructure. Further, this clustering encourages the processes of learning and cooperation in society as a whole. Thus, the clusters gain a competitive advantage for markets confronting the world's dynamic competition. This advantage is exemplified in the case of the Mexico City telecommunication cluster.

In Chapter 4, "Pooled Labor Market and Locational Factors for the Exporting Maquiladora Industry in Mexico," Cuauhtémoc Calderon Villarreal and Jorge Eduardo Mendoza analyze the benefits from clustering. Although the traditional approach suggests that the localization of the export-oriented maquiladora industry in Mexico can be traced to lower labor costs and proximity to the U.S. market, they offer a new view. Pooled labor markets attract investment into the region, resulting in positive externalities arising from the agglomeration economies.

In Chapter 5, "Export-Oriented Production and the Agricultural Labor Market in the Northwest Border Region of Mexico," Sonia Lugo Morones examines issues of growth and balance of payments, arguing that in the experience of Baja California the main constraint for long-term growth is associated with demand-side economics because the supply-side is constantly fortified by capital coming from abroad and by the migratory flows from less dynamic states of Mexico. An analysis of the balance-of-payments reveals that the composition of demand is critical for economic growth. In industrial economies led by foreign markets and exporting firms such as those of Baja California, the proportion of demand captured by trade is high. This may encourage or discourage growth, depending on the degree of integration of local agents to meet the changing needs of international corporations. Most of the pressure on demand comes from the maquila salaries paid to workers, Lugo argues, with the problem being poor productive linkages with local firms. Therefore, the multiplier effect from foreign investment and trade is small as is the potential for growth. In order to encourage growth, Lugo proposes that local firms fortify their linkages to the exporting firms and that the economy should specialize in high income-elastic commodities.

In Chapter 6, "Balance of Trade and Economic Growth in Baja California: An Application of the Kaldor-Dixon- Thirlwall Approach," Juan M. Ocegueda Hernández takes up the case of the export-oriented agricultural sector in Baja California. Strong linkages to the Southern Californian economy offer an important complement to what is produced in Mexico's agricultural sector.

Ocegueda-Hernández focuses on the agricultural labor market to suggests that structural change regarding location, education, salaries and activities is being developed.

In Chapter 7, Alejandro Mungaray and Martín Ramírez-Urquidy analyze "Production Efficiency and Credit Availability for Micro and Small Firms in Baja California." Although the Mexican side of the border is pushed by the international dynamic in which export-oriented big manufacturers lead and benefit from the global environment in the region, this situation has not been beneficial to the large group of small firms operating in the metal and food products industries. The resulting problem of credit constitutes one of the contrasts in the region: one part of the productive system (the large companies contributing the greatest economic value) operates at the level and speed of the international markets, participating in the trade flows, while the other part (the micro and small firms that are the greater in number) faces financial and market constraints. The authors investigate the productive structure by taking a sample of small firms operating in the metal and food-products industries and then estimate the production functions. They fmd no association between credit availability and productive efficiency-either because of the high interest rates on loans in the Mexican financial market or the deficient allocation of resources by managers. Instead of allocating resources to cover some costs, many managers simply restructure loans, rather than developing new capital investment to encourage productivity.

In Chapter 8, Emilio Hernández, Alejandro Mungaray, and Juan M. Ocegueda-Hernández, focus on "Global and Local Industrial Development in Tijuana: Origins and Tendencies." The global interaction involves Tijuana's economic and social interactions with San Diego. The location of Tijuana, close but not adjacent to San Diego, accounts for Tijuana's socioeconomic and urban characteristics. Further, they see the physical growth of Tijuana as involving land absorption, which is determined by maquiladora expansion. The maquilas require land for worker housing as well as for physical plants. Hence, Tijuana's contemporary residential growth· is biased toward the northeast where most of the maquiladora industry is concentrated.

Conclusion

Readers will be pleased to find that the chapters in this book provide a fresh introduction to some of the main issues and challenges facing those in Mexico's border region, especially in Tijuana. By redefining the issues, this volume by Mexican scholars under the leadership of UABC presents possibilities for developing a new society-one that is capable of becoming involved in the design and implementation of policies beneficial to both sides of the border.

The authors argue that policy makers must consider the asymmetries and interdependencies among social and economic agents in order to take advantage of their complementarities.

This volume prompts us to reconsider how the public and private sectors (including social organizations, chambers of commerce, industrial organizations, public and private universities, research institutes, NGOs, and bilateral organizations) should be taken into account by national, local, and regional governments in order to develop the dynamic planning needed to accommodate rapid change at the U.S-Mexican border. Coordinated intervention by the U.S. and Mexican governments is required in order to create the mechanisms and regulations through which the public and private sectors on both sides of the border can cooperatively establish selective programs and policies oriented to benefit the region's diverse social and economic groups, especially those at the margin of institutional support.

Industrial policy planning can learn from past mistakes to resolve problems. One of the major implications of the research presented in this book is that the establishment of intellectual as well as physical clusters is necessary to mitigate the adverse effects of globalization. Such clusters can make possible the development of urban and regional planning of integral policy to leverage the impact of development of new education, technology for industry and social conditions guided by comprehensive allocation of financial resources from national and multinational sources. The objective is to develop a healthy social and economic convergence of forces along the U.S.-Mexico border, especially in the case of Tijuana.

In summary, this volume shows us how academicians can help policy makers rethink the elements that need to be taken into account as they seek positively to develop a dynamic region that is always many steps ahead of the rules and regulations by which society seeks to manage development.

The situation in Tijuana illustrates how the entire Mexican border is blending into cross-border economic interactions with its counterpart city in the U.S. But Tijuana is also blending into Greater Los Angeles, which in the future will require further analysis. The unbroken chain of light along Interstate 5 from Tijuana to Los Angeles proper is a virtual bridge of traffic melding Tijuana and northern Baja California into Los Angeles County, as workers commute both ways to provide the force of laborers, managers, and investors who are capitalizing on the busiest border crossing in the world-Tijuana.

1. Evelyn Iritani, “Moves to Baja Profit Tech Firms: Low Costs and Links with San Diego Have Created and Expanding Medical Device Industry in Region, Spurring New Entrepreneurial Dreams,” Los Angeles Times, March 10, 2006.

2. Health Net charge to patients for generic medicine is the same in the U.S. and Mexico: $5.

3. Abigail Goldman, "Cross-Border Plan Offered by Health Net," Los Angeles Times, March 15, 2006.

4. Evelyn Iritani, "They're Building in Baja, and Boomers art' Buying," Las Ancclcs Times, Fcbru.irv 20,2000.

5. "Huge New Container Port 80 Miles South of Ensenada?" 'Lectronic Latitude: Breaking News and Hotlinks. Mill Valley, CA: Latitude 38 Publishing Co., Inc. http.z /www.latitude jx.corn/ LectronicLatI2004/0804/ Aug20/ Augao.html; accessed January 27, 2006. "Major Seaport Proposed for Baja California Norte: Chinese and Korean interests want a port facility in Baja California." Baja Insider.com: The VVebzine of Traveling and living in Baja California. Cabo San Lucas, BCS/La Paz, SCSI Las Vegas, NV: Desert Digital LLC. http://wwwbajainsider.com/environment/port-punta-colonet. htm; accessed January 27, 2006.

6. See articles on Port Colonet by Diana Lindquist ("Punta Colonet Will be Built from Scratch, Official Says," San Diego Union Tribune, March 28,2006) and Will Weissert ("Mexico:Top Private Interests Look to revamp Pacific Ports," Associated Press March 21,2006) in Baja Investors, March, 2006, http://wwwbajainvestors.net/currentevents.html; accessed April 30, 2006.

7. Panama's plan to double the capacity of the Panama Canal by 2014 is not expected to relieve congestion in the Three Ports region of Southern California, thus requiring the building of Port Colonet. On Panama´s plan and Colonet, see Chris Kraul and Ronald D. White, “Panama Is Preparing to Beef Up the Canal,” Los Angeles Times, April 25, 2006

8. Although Americans have often been surprised to see that their German, French, and Italian coffee-makers were made in Mexico, by 2005 only Germany had not moved its big plants from Mexico to China. The exception has been the low-end coffee-maker Mr. Coffee®, which hold long been proud of being “made in the USA” but now has shifted manufacturing to China.

Copyright © 2006 - 2009 PROFMEX. All rights reserved |